One hundred and fifty years ago, members of the Fenian Brotherhood sought to force Britain’s hand by creating disturbances along the Canadian border. The raids failed, but they led to an unexpected outcome in 1867.

OTTAWA, Ontario – It was civil warfare, with some almost comic sidelights, and it might have been lost in the mists of time but for a discovery in the attic of a Virginia home 13 years ago.

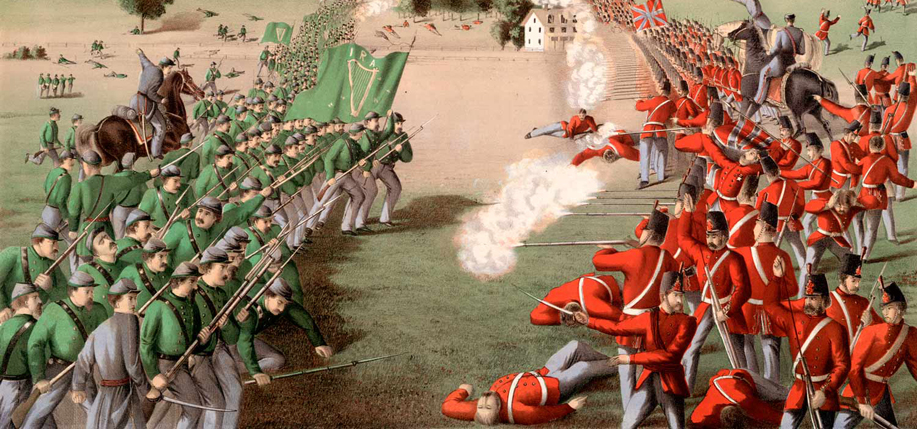

The 23 paintings discovered there depict one of the Fenian raids in which Irish American Civil War veterans crossed into Canada near Buffalo, New York and won two battles against British Canadian forces.

It was one of several raids between 1866 and 1871 aiming to hold portions of Canada as a bargaining chip to make the British leave Ireland.

Unwittingly, though, the modest invasions served to draw the diverse regions of British North America together and cement Canada’s confederation in 1867.

The watercolors depicting battles at Fort Erie and Ridgeway in Ontario are part of an exhibit at the Canadian War Museum in Canada’s capital. It is called The Fenians – Unintended Fathers of Confederation and is on display until September 4.

The Fenian name was coined by founder John O’Mahony, after the Fianna Eirionn, the ancient Irish warriors. As war goes, this was about as nice as it gets despite a handful of dead on both sides. The Irish Americans – led by Lieutenant-Colonel John O’Neill and mostly Union soldiers with a smattering of Confederate veterans – left the Canadian turf they occupied as they found it.

“They were disciplined soldiers who operated by the strict rules of war at the time,” says museum historian Dr. Peter MacLeod. “They behaved very well towards the civil population. They didn’t loot and they treated Canadian prisoners very well. They were there in an attempt to free Ireland from the British” and had no grudge with citizens.

History is fuzzy on who came up with the plan to capture Canada and exchange it for Ireland, “but the irony is that while they fail to free Ireland, what they do is help the confederation movement in Canada because it gets Canadians thinking about uniting for protection against attacks,” MacLeod says.

In a sense, then, the Fenians created Canada.

The Fenians also raided what is now New Brunswick and Quebec. Elections held following those threats strongly favored Confederation. A final raid in Manitoba in 1871 to occupy a customs house was in fact snuffed out with help from America authorities.

Says Stephen Quick, director general of the Canadian War Museum: “While the Fenian threat is now a distant memory, its unintentional contribution to our nation’s birth is worth remembering as we celebrate Canada’s 150th anniversary this year.”

The watercolors are by Alexander von Erichsen, a German-born artist who lived north of Toronto at the time of the Fenian Raids and later moved to Virginia. The Fort Erie Historical Museum, just across the border from Buffalo, acquired the paintings after they were discovered in Virginia in 1994.

The detailed illustrations and captions tell the story of the largest Fenian Raid on British North America, when 800 Irish Americans occupied Fort Erie on June 1, 1866, moving on to defeat about 900 Canadian militiamen in the rural community of Ridgeway later that day. The following day, they marched back to Fort Erie, where they defeated another Canadian force. But although the Fenians won these battles, they ultimately lost the war. Ireland remained a British possession, and British North Americans united to form the Dominion of Canada in 1867.

Macleod said the Fenians mobilized in part because of their Irish blood, but also because following the Civil War jobs were scarce. And the mix of Union and Confederate veterans was a result of “their shared Irishness overcoming any lingering bitterness from the war.”

But the movement faded as the soldiers began to find jobs.

MacLeod noted a song the Fenians sung as they mobilized on Buffalo.

We’ve won many victories,

along with the boys in blue

We’re off to conquer Canada because there’s

nothing left to do.

Even if the Fenians had continued their raids, McLeod suggests there was little chance of success.

“They had defeated amateurs at Ridgeway and Fort Erie but now the British Army was on the march,” ready to send them back to the United States.

The Fenians had moral support in the U.S. but after the raids in Ontario many were rounded up, charged, though later released.

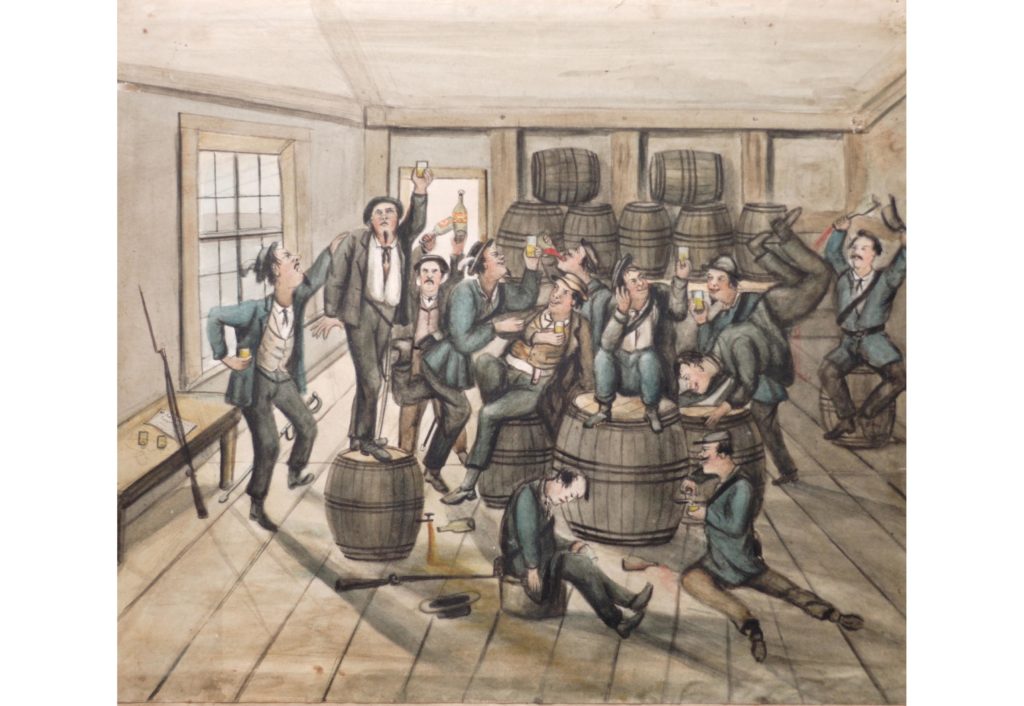

Some of von Erichsen’s watercolors show a bias against the Irish American cause. One painting of Fenians carousing in a New York tavern shows one man trying a drunken handstand on a barrel and in one scene, a Fenian officer seizes a rifle from a Canadian soldier, swearing the weapon will never shoot another Fenian. He smashes the rifle butt on a stone, killing himself as it fired.

The 23 paintings, one showing Fenians caring for a wounded Canadian, found their way back to Canada from Newport News, Virginia after an aunt of Vivian Jewel, the last surviving relative of von Erichsen’s granddaughter, passed them on.

Vivian and husband Charles traveled to Canada and the Fort Erie area in 1990 and by chance met historian David Owen, author of The Year of the Fenians, who put them in touch with the Fort Erie Historical Museum.

The paintings return there in September for permanent display.

Back in Ottawa, there is more Irish history at the Bytown Museum, which sits at the foot of Parliament Hill, Canada’s seat of government, and just beside the Rideau Canal, dug mostly by the Irish and French Canadians in the 1820s and 1830s.

Between 2,000 and 6,000 men worked on the canal, which connected the Ottawa River with Lake Ontario, and it was dangerous work as men died due to malaria or poorly executed black-powder charges. Reports suggest about 1,000 died in the canal’s construction, but Grant Vogl of the Bytown Museum believes that figure is low.

He points out that history, until recently, has treated the Irish and French Canadians as simple laborers. But the discovery of documents shows many Irish did the skilled stonemasonry.

When the canal was completed, those Irish were out of work and there was an organized attempt to break the French Canadian lock on the logging industry.

It was a lawless time, and accounts, notes Vogl, indicate that brawling Bytown was one of the rowdiest outposts in Britain’s colonies. Fuelled by alcohol, fighting broke out up and down the Ottawa Valley, including the Ballygiblin Riots of 1824.

Despite all that, Ottawa was selected as Canada’s capital, and today, people who identify with their Irish roots compose about 20 per cent of the region’s 1.1 million population.

℘℘℘

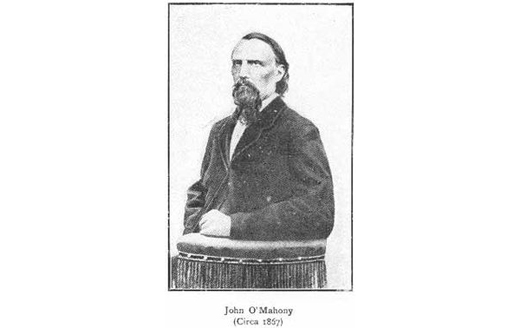

JOHN O’MAHONY

John O’Mahony, the man who ordered the Fenian raids, was born into a wealthy family in1815 near Mitchelstown, County Cork. After his part in the failed Young Ireland rebellion of 1848 he fled to the United States where he founded the American branch of the Fenian Brotherhood, an Irish nationalist secret society active in Britain and the United States during the mid-19th century.

O’Mahony attended Trinity College and became a respected Irish scholar and linguist, though he did not graduate. By 1853 when he arrived in New York he’d become a prominent leader of Irish resistance to British rule. He settled in New York, where he helped organize the Emmet Monument Association, a predecessor to the Fenian movement.

In 1857, O’Mahony formed an American support organization for the parent organization under his own leadership. He named it the Fenian Brotherhood, inspired by the Fianna, legendary warriors in ancient Ireland. O’Mahony had recounted their battles in his own translation of a 17th-century Gaelic history of Ireland. By 1865 the Fenian Brotherhood had grown large and prosperous, and it was able to send both arms and money to Ireland.

O’Mahony reluctantly backed the Fenian decision of 1865 to make a series of military raids on Canada, part of a scheme to take Canada hostage for the cause of Irish freedom. His popularity plummeted after a failed attack against Campobello Island in New Brunswick. There is no evidence he participated in that raid or the successful mission in Ontario. He resigned but returned in 1872 to resume leadership.

O’Mahony died destitute in New York and his body was returned to Dublin. It lay in state in the Mechanics’ Institute after the archbishop of Dublin, an anti-Fenian, refused it permit it in the procathedral. O’Mahony’s funeral procession to Glasnevin Cemetery on March 4, 1877, was reported to have been attended by more than 70,000 nationalists.

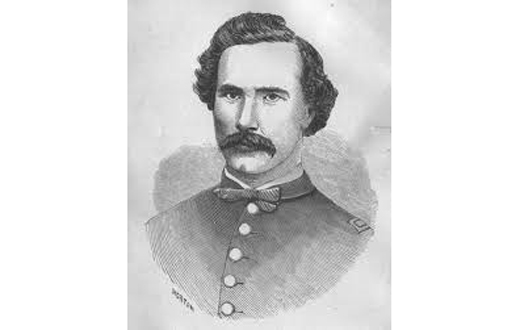

COLONEL JOHN O’NEILL

Colonel John O’Neill, who took last-minute command and won battles over a Canadian militia in Ontario, was born in Drumgallon, Clontibrit County Monaghan and emigrated to New Jersey in 1848 where he worked in a variety of publishing jobs.

As an officer in the 5th Indiana Cavalry in the Civil War, he was remembered as a daring fighting officer, but bristled he had not received promotion, which led to a transfer to the 17th United States Colored Infantry as Captain. He left the Union Army prior to the end of the conflict.

O’Neill successfully routed the opposition at Ridgeway, Ontario in 1866 with a ruse that fooled the defenders. He had no cavalry but using a handful of officers and riderless horses to alter the defense strategy, exposing the Canadian militia under British leadership to infantry attack.

But his next ventures into Canada in 1870 and 1871 were dismal failures. The Battle of Trout River in Quebec ended in a rout, O’Neill was arrested by a United States marshal and charged with violating neutrality laws. O’Neill was imprisoned, sentenced to two years, but he and other Fenians were pardoned by President Ulysses S. Grant.

Recanting on a vow to never attack Canada again, he was persuaded to lead an attack on the Hudson’s Bay Company’s post at Pembina, Manitoba in October 1871, an area was then disputed between the U.S. and Canada. He was arrested by American troops.

O’Neill later devoted himself to relocating Irish immigrants from eastern slums to the west. He died in 1878 of a paralytic stroke.

After his death, the area he moved many Irish to and resided in, then called Holt City, was renamed O’Neill and is now called the “Irish Capital of Nebraska.” ♦

What is equally fascinating about this story is how they procured the muskets they used in 1866 and then had them converted into Breech-loaders in 1869 for the 1870 raids. They procured an abandoned arms factory in Trenton New Jersey, re-named it Pioneer Arms Works and performed all the conversions there in secret.

Again, it’s an educational story. While the Fenian invasion of Canada is well known, stories such as “O’Neill” Nebraska is not! If I had known such a place existed, I would have visited it when I was in Nebraska.

https://cityofoneillnebraska.com

Thank you so much for publishing this history. I am the great great grandaughter of General O’Neill. Every time I read something about grandfather, I learn a little more.

I was in O’Neill, Nebraska June of 2022 when they dedicated a bronze statue of grandfather and last March for St. Patrick’s Day. The citizens of O’Neill are very proud of their Irish ancestry.

Grandfather is buried in Omaha, Nebraska in Holy Sepulchre Cemetary, and his gravestone is engraved with: “By nature a brave man. By principal a soldier of Liberty, He fought with distinction for his adopted country and was ever ready to draw his sword for his native land. — To perpetuate his memory this monument was erected by the Irish Nationalists — God Save Ireland” His grandson, my great uncle, John F O’Neill is buried next to him. Again, thank you.