“She was a mother to the motherless; she was a friend to those who had no friends; she had wisdom greater than schools can teach; we will not let her memory go.”

Sara Cone Bryant, from “Margaret of New Orleans,” in Stories to Tell Children

(Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1908)

There’s a small park in New Orleans, on the corner of Camp and Prytania Streets, which exists solely to house a statue of an elderly woman holding a young girl. The woman is homely and stout, the girl is angelic and the message is one of love and caring. The plaque on the statue has only one word, “Margaret.” In New Orleans, there’s no need to include a last name – everyone knows.

She’s Margaret Gaffney Haughery, a beloved character in New Orleans history, known as “The Angel of the Delta,” “The Bread Woman,” and, more than anything else, “The Mother of Orphans.” The Big Easy, known for good times and raucous celebrations, still recognized a great soul in its midst and claimed this austere, religious woman as its very own patron saint.

Margaret may be unknown everywhere else but she was one of the most remarkable immigrants of the 19th century. She was an illiterate Irish washerwoman who faced down the terrible misfortunes of her life with grit and charity, dedicating her life to orphans, the poor and the displaced. To finance her generosity, she embarked on remarkable career trajectory: servant-peddler-washerwoman-dairymaid-baker-businesswoman-philanthropist.

She left Ireland with her family when she was five in 1818, “the year without a summer.” The crops had failed, the Gaffneys were starving and, as Margaret later pointed out, her father was “an uncompromising foe of Saxon rule.” It took six grueling months for them to arrive in America eventually settling in Baltimore. They were still destitute when Yellow Fever took her sister and soon after, her parents.

Another family member, a brother, just disappeared. At nine, Margaret was alone, an orphan working as a house servant and peddler to support herself.

She was 21 when she married a fellow immigrant, Charles Haughery and in 1835, the couple moved to New Orleans where Margaret gave birth to a daughter, Frances. Although the Irish would soon be a major force in the city, Margaret and Charles faced the resentment directed at the new wave of immigrants; vicious prejudice was reserved, particularly, for the women who were perceived as ugly and mannish. An 1837 fiction piece in The Daily Picayune wrote about the mock trial of an Irishwoman, too drunk to be around decent folk so she was sent to the House of Correction. This, it should be added, was a “humor” article.

Margaret was a stranger in this strange world when Charles died and when, months later, the ultimate tragedy struck – her infant daughter succumbed to SIDS, a disease unknown and unnamed at the time. A widow and an orphan who had buried her only child, she railed against her fate, “My God! Thou hast broken every tie: Thou hast stripped me of all. Again I am all alone.”

A very formidable nun, Sister Regis Barrett of the Sisters of Charity, came to the aid of the impoverished 23-year-old widow giving Margaret a free room. More importantly, Sister Regis helped her channel her grief by directing her to work at the Poydras Orphan Asylum. This was her salvation and the beginning of her life as “The Mother of Orphans.” She worked as a laundress at the elegant St. Charles Hotel and divided her time between washing sheets at the hotel and giving love (and her wages) to the orphans at Poydras. To secure more clothing and food, she went street to street, store to store, begging – this was her first foray into what would later be her great mission, fundraising. She once entered a grocery store asking for donations for the children. A cheeky clerk said he would only give her as much as she could carry. A few minutes later, she returned with a wheel barrel, stocked it with enough supplies for months, and wheeled it, unaided, on the long journey back to the orphanage.

Margaret wanted to be sure the children always had enough milk so she used her savings to buy two cows. She milked the cows, fed the children, then put the surplus milk on a truck, which she drove around the French Quarter. With profits from her milk truck, she started a dairy with 19 cows. Improbably, the woman who couldn’t read or write, the woman who owned only two dresses, was becoming a savvy entrepreneur. An entrepreneur who would, in time, buy land, businesses, and machinery and take on the all-male business community with lawsuits and injunctions. It helped that she was a widow (married women weren’t allowed to own property) known throughout New Orleans for her benevolence – profits she saw from her businesses went into constructing more orphanages and shelters.

She parlayed her dairy success into another venture, buying a failing bakery and creating Margaret Haughery & Company, the first steam bakery in the South which, in time became one of the largest bakeries in the country. She expanded the product to cakes, crackers, cookies, flour, and even macaroni, increasing profits not by raising prices but by expanding production. A visitor at the time watched the company in action, “men were carrying drums of flour into the bakery while others were coming out of the warehouse with large barrels of bread and crackers.” Always known as a practical woman she co-invented a more efficient oven and discovered a way to package crackers keeping them for weeks. Now she was officially “The Bread Lady” as she personally delivered her bread to the poor of New Orleans.

When the Yellow Fever hit New Orleans, the epidemic took over 8,000 lives and many more lay ill and dying. This was the same disease that claimed her family but Margaret went from house to house, nursing the victims regardless of race or means, promising dying mothers she would be a mother to their children, a promise she kept.

During the Civil War she helped feed the city, defying the curfew and the Union Army. There’s a story about Margaret, in the middle of a battle, attempting to pass a barrier to feed starving citizens. She was stopped by the Union’s General Benjamin Franklin Butler.

“You are not to go through the barrier without my permission, is that clear?”

“Quite clear” Margaret replied (among other more pointed words) and walked through the barrier. The following year, during the siege of Port Hudson, she was brazen enough to solicit – and receive – donations for her orphanages from the Union army.

The epidemic and the war filled New Orleans orphanages, prompting Margaret to construct seven more (including St. Elizabeth’s Asylum, later the home of Irish-American author Anne Rice). It’s important to note that her orphanages were ecumenical and inclusive, open to black and white, Protestant and Jews, with no questions asked about paternity.

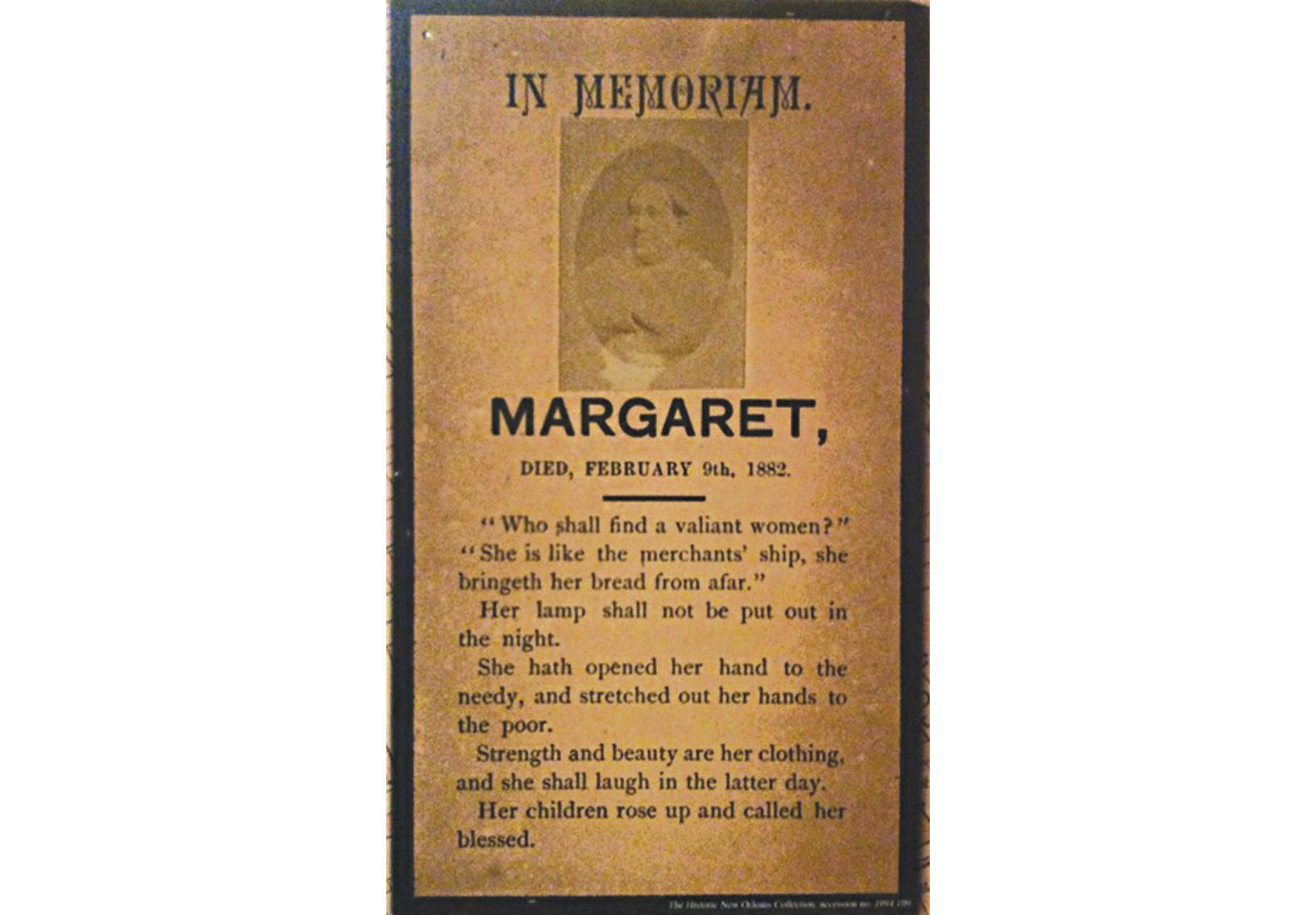

She died in 1883 at the age of 69 and was honored with a state funeral. The city shut down and two governors, a mayor, and an archbishop were her pallbearers. Crowds of people, including every orphan in New Orleans, lined the street to pay tribute as her cortege passed by. The Times-Picayune was in black borders and ran an obituary on the front page titled, “Our Margaret.”

“The people of New Orleans, many of them, are wedded to pleasure and sensual delights; but they recognize true religion when they see it, and they turned out en masse to do it reverence when they followed Margaret to the grave.”

Soon after her death, the city erected her monument – only one other statue of a woman existed in the country at the time. When it was completed, Catholic, Jewish, and Protestant orphans came from every asylum in the city to dedicate the monument and the park, “Margaret’s Place.” Margaret’s Place survived Katrina but time had still done its damage. The citizens of New Orleans raised funds for its restoration and, in 2015, the refurbished park and statue of Margaret was completed. Even her native Leitrim, to which she never returned, has restored her homeplace and welcomes tour groups to “walk in Margaret’s footsteps.” Today, her institutions survive as homes for the elderly and infirm.

The immigrant washerwoman left an estate of $50,000 (today estimated at 1.2 million dollars) all of which she left to charity. She signed her will with an “X.” ♦

We take great pride in leitrim that Margaret was born here and that she made a great contribution to America.

http://www.margaretsbirthplace.com/

What an amazing lady. May her memory always be a blessing.????????

A great woman and a great article: I’m familiar with her park and the area around it. I think I may have referenced her in my article published in: “Irish America Magazine.”

Harry Dunleavy

What an amazing woman. I wish I had known about her when I was in New Orleans in the 1950s I would have loved to visit her park.