Anne Anderson, Ireland’s Ambassador to the United States, reflects on her career, her role in the United States, and Ireland’s centenary.

℘℘℘

It’s hard to be an Irish American living in Washington, D.C. and not run into Anne Anderson, Ireland’s first woman Ambassador. When I point this out as we sit down in the conference room of the Irish Embassy, she laughs. “I am everywhere,” she concedes. “It’s a requirement of the job, but is also a reflection of my own interests and personality and my sense of how you do the job. It’s very important for the community, I think, that they see their Ambassador.

“Every day I remind myself that I am Ambassador to the United States, and not just to Washington, D.C. I interact a great deal with our six consulates around the United States. I really put a strong emphasis on getting around the country, and being present on occasions where Irish people are engaging or being honored.”

As we talk, it becomes clear that along with her status and her poise as a diplomat is a very reflective mind. As she considers her current position, she points out that “It is an extraordinary privilege to be representing Ireland abroad. There is such a level of trust and such respect for the role of ambassador. It’s really respect for Ireland. So you have to try to live up to that sacred trust. It demands all your commitment and dedication and every ounce of your energy.”

The Ambassador’s CV boasts a series of considerable accomplishments. A native of Clonmel, Co. Tipperary, she was appointed Ambassador to France from 2005 to 2009. She served as Permanent Representative of Ireland to the United Nations in both Geneva, where she chaired the 1999 U.N. Commission for Human Rights, and in New York. She also served as Ireland’s Permanent Representative to the European Union in Brussels, where she led the Irish team during Ireland’s 2004 E.U. presidency.

Even with all of these accomplishments, the Ambassador readily points out that serving as Ireland’s ambassador to the United States is a unique opportunity.

“The greatest concentration of our diaspora is here. It makes it very special when you have 35 million people of Irish ancestry. Nowhere else in the world do you have that concentration of the diaspora,” she says.

“It’s the unique ties of history, the ties of blood, kinship and family, but that is reinforced by the contemporary connections and economic relationships.”

When asked what she finds most gratifying about her job, she ponders for a moment. “Hard to choose,” she states. “It’s a multi-faceted job, because you have the different components – you have the economic component, working to further investment, trade, and tourism. You have the political component – maintaining the relationships with the administration, and the Hill. And then you have the people-to-people element, helping to strengthen Irish culture, affirming all the achievements of Irish people and Irish Americans. It’s being present for people in the bad times to express solidarity and sympathy, and being there in the good times.

“I think the people-to-people part of it has to be the most gratifying,” she concludes, “because you see the importance for people of the presence and the affirmation of the Irish Ambassador. And there are wonderful occasions, like the Special Olympics last year in Los Angeles. To be there, to be able to cheer on the athletes who are doing so, so well.”

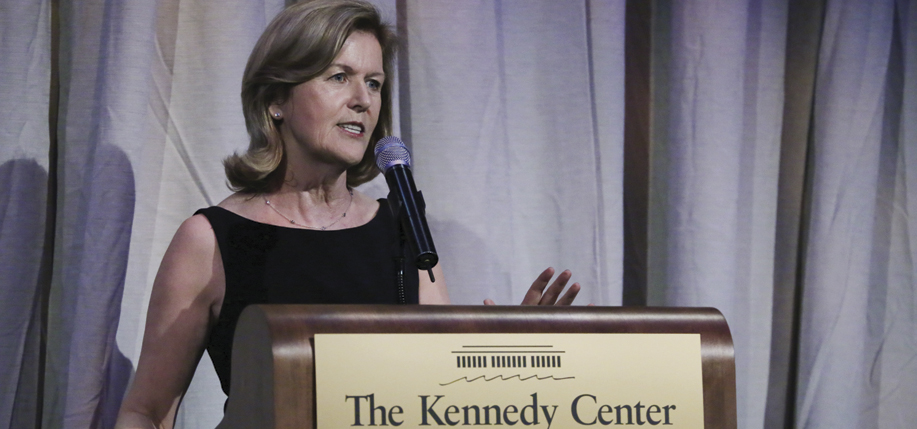

When we meet, the Ambassador is quick to ensure my comfort. She is poised, yet warm, with a ready laugh. She was about to host the launch of Ireland 100, a comprehensive celebration of Irish arts and culture at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. in honor of the centenary celebration of the Easter Rising – the catalyzing event that propelled Ireland toward independence. For Ambassador Anderson, this celebration is a labor of love, years in the making.

Celebrating the arts is her métier. “I’ve always had a great love particularly for literature and poetry. I love to see really interesting, substantive, challenging interpretation of the arts here in the United States.

“I was kind of brought up on poetry,” she continues. “My mother had very little formal education. She left school at 15, perhaps barely 16, but she loved poetry and kept books where she had transcribed so many of the great poets and would constantly read those to us as children. My daughter is a literary agent. The line of women from my mother to my daughter . . .” she laughs, “I am surrounded by words!”

In addition to her love of the arts, the Ambassador’s life and work have been characterized by a passion for inclusivity.

“That is something that I have always, instinctively been very attached to,” she admits, “a deep sense of equality, equal rights. Of course all my time at the United Nations reinforced that attachment to equal rights, women’s rights, human rights.”

Given her agenda of inclusion, the past year has proven to be particularly gratifying for the Ambassador. Almost a year prior to our meeting, Ireland voted to extend civil marriage rights to same-sex couples. She is quick to also cite that this year marked the first time an Irish LGBT group marched in New York’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade.

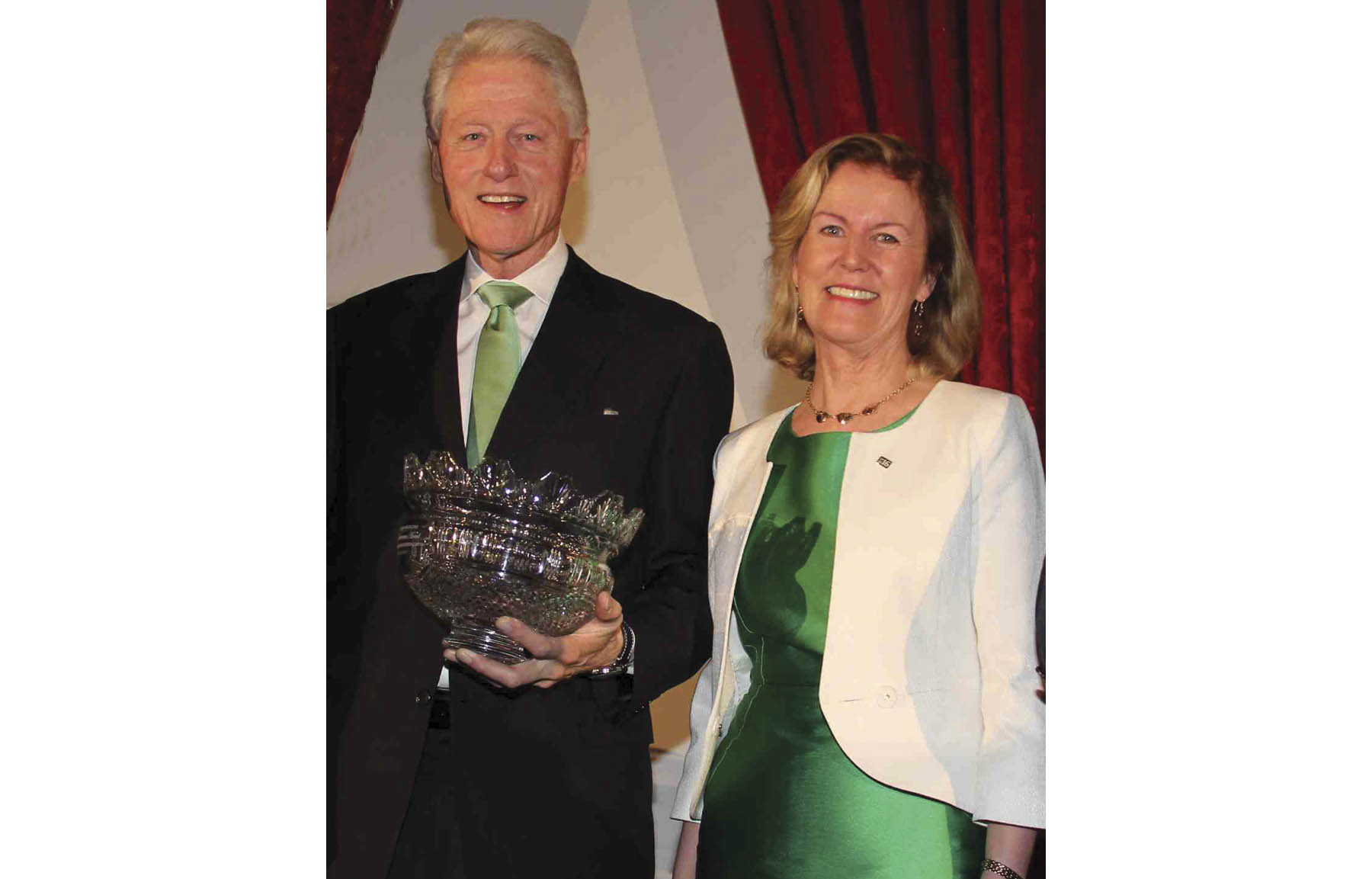

Additionally, the Ambassador herself broke one more glass ceiling for women this year. In March, she was the first woman inducted into the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick. In her acceptance speech in Philadelphia, she hailed these developments, asserting, “There are no second class citizens; no children of a lesser God.”

“I feel that if we truly have opportunities for young women of the next generation, we would see them achieving their mark across every sphere of activity,” she maintains. “That’s my hope.”

“I think we have to look at what is preventing women from rising to the very top levels,” she continues.

“There are more young women than young men in third level education. One would hope that means that as those cohorts of highly qualified young women work their way through the system, we will see structures become far less pyramidal and more equal.”

The Ambassador sits forward and begins pushing her fingertips along the tabletop, as if pushing women toward a place of equal opportunity.

“I think time will take care of some of it,” she continues, “but we have to work very actively to make sure that what we see happening now for young women will actually be reflected in their rise through all the ranks so they get into the top positions.”

Another item on the Ambassador’s agenda is immigration reform and advocating for the rights of the undocumented Irish living in the United States. This is a topic that resonates with her, professionally and personally.

“My parents both came from small farming backgrounds. My mother wrote her memoirs for the family, and she describes scenes of her elder brother leaving for the United States – the American wake – and her mother weeping, ‘I will never see my son again.’ And she never did. So I had an uncle who came over, absolutely unqualified, and struggled to make a living.

“Of course we never recommend that anyone allow themselves to come into that situation,” she points out, “but I feel that if my life path had taken a slightly different turn I could easily imagine myself in their situation. In the vast majority of cases they didn’t intend to become undocumented.”

“I’ve met many of them,” she continues. “You know the difficulties of their lives lived in the shadows, what it means not being able to travel back to Ireland – they can travel back but they can never return. Many came a number of years ago, so their parents are becoming older and sicker, sometimes becoming terminally ill in Ireland and that awful, awful dilemma, do you go and risk the life you have here or do you stay and miss being with your parents at a time when they need you most? The awful emotional pull of that is something that I think any of us can relate to.”

The Ambassador has clear, light blue eyes that become shadowed as she looks into the middle distance and shares this recollection.

This is an issue she feels quite personally. When I point this out, she maintains, “It’s a policy priority for our government, but I feel very close to the people I meet who are undocumented. They’re people I can very easily identify with.”

We are clearly over our allotted time. The Ambassador dashes out of the room to find me a program for the Ireland 100 festival and then realizes that it’s her personal copy, already marked with the events she’s planning to attend. “We have over three weeks of performances with hundreds of performers and I expect to get to most of those performances. I’m not quite sure how I’ll juggle them all,” she laughs.

This celebration is about more than Irish culture and arts. To her and her fellow citizens, this celebration is a muscular assertion of Ireland’s identity today as it reflects on the past century and looks toward the next 100 years.

“What is really wonderful about it is the blend of the classical and the cutting edge,” she says. “It’s kind of to challenge and interrogate as the two meet. What we want to say is ‘This is who we are. This is how contemporary Ireland looks and feels and sounds and that is really at the heart and soul of how we’re representing the centenary year.’ We should get out of our comfort zone.”

In reflecting on how Ireland is observing the centenary, she notes, “It’s looking back at the one-hundred-year journey and the point at which we have now arrived and setting the compass for the years ahead. Would the 1916 generation have been proud of us? How can we build on what’s good and course correct in areas where we have fallen short? If the centenary helps us to move along on that path, it will be such an achievement. Yes, it’s about commemoration but this year should illuminate and interrogate. It should enlighten us and refresh us.”

In asserting Ireland’s identity for a new century, the Ambassador points out the importance of Ireland’s role in U.S.-Europe relations.

“In Ireland, we face both ways,” she states. “We are a hugely committed part of the European family and we have unique ties to the United States. I think we can help interpret Europe to America and America to Europe because of the particularity of our position.

“All those years I spent at the United Nations makes me very conscious of our profile and our identity, which is not often understood fully by the business community here or by Irish America – how much Ireland engages in peace-keeping, how strong a development aid policy we have, how much we’re engaged in international human rights issues.”

“The imprint of the famine is so strong in Irish America, so when I talk, I think my U.N. background is helpful in making that present day connection about how issues of hunger and food security are fundamental to our development policy and our foreign policy and connecting that with the historical memory of the famine.”

Seamus Heaney, a favorite of the Ambassador’s, once said, “I’ve been in the habit of helping people.” One could accuse Ireland’s U.S. Ambassador of the same habit. Her life’s work has been dedicated to an idea best summed up in a line she often quotes from the Proclamation of 1916, “to pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation and of all its parts, cherishing all of the children of the nation equally.”

It is a noble and endless quest, one for which she is eminently well-suited. ♦

Leave a Reply