Two years ago, Maureen Mitchell, who currently serves as the president of GE Asset Management’s Global Sales and Marketing organization, moved back into an apartment in her hometown – Manhattan. Though the city may have changed, Mitchell is still very much the daughter of Irish immigrants and a textbook example of the first-generation American Dream. She sat down with Irish America to discuss her work, her upbringing, and what her success means to her.

℘℘℘

Maureen Mitchell grew up in the Yorkville neighborhood of Manhattan, the daughter of Irish immigrants from Galway (her mother) and Sligo (her father). At the time, it was a Catholic working class neighborhood, filled with immigrants from Ireland, Germany, and Hungary, and her parents met at a local parish dance. The middle of three children, Mitchell worked from an early age – her first job was babysitting neighborhood kids. Since then she’s never really stopped. It’s not much of a stretch to say her life has been defined by her jobs and her dedication to them. It comes from her Manhattan immigrant mentality – work hard, succeed, and use that success to help as many other people as possible.

After she graduated with her B.A. with honors in history from the City College of New York (where she now sits on the board), Mitchell taught at James Madison High School in Brooklyn. After a short time, she went back to school and earned a master’s from Fordham University and began managing a non-profit in her late 20s. She then pivoted to the private sector, taking her first job in finance in 1981 at Banker’s Trust.

Though she didn’t know much about the industry at the time, she learned quickly and spent the next 15 years at various firms, increasing her responsibility, before landing at Bear Stearns in 1998. She stayed until the 2008 collapse before joining GE Asset Management, the investment management arm of GE.

Today, she oversees all global marketing and sales for the firm, strategically leading and prioritizing the efforts of her team as it builds partnerships with other investors. She’s known as a leader that pushes her employees hard to achieve results, but who also exhibits a management style that is rooted in collaboration, trust, and individual ownership.

“Maureen is demanding and is always clear about her expectations,” says Chris Linehan, who works closely with Mitchell as GE Asset Management’s communications director.

“At the same time she is fair, encouraging and allows you to develop your own sense of purpose and accountability. She’s committed to creating a true balance of empowerment and consultation that informs the way we work together. Her door is always open and anyone can stop by to bounce ideas off her and come to agreement on issues in a very informal and supportive way.”

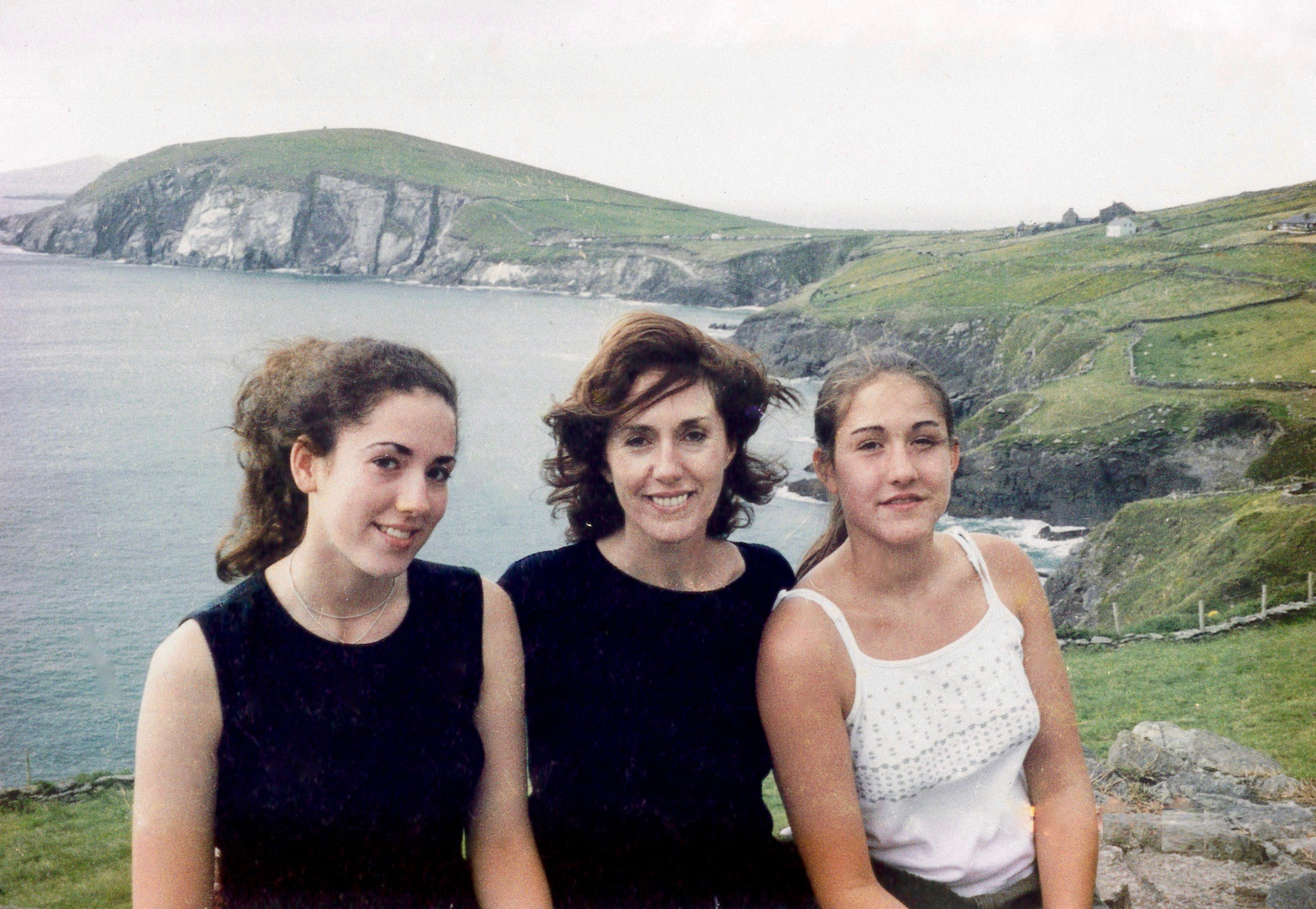

In January, Mitchell traveled to Guatemala with the non-profit She’s the First, where she has sat on the board since 2014. The organization provides scholarships to girls in low-income countries who will be the first females in their families to graduate from secondary school. It’s a natural fit for her. Women have always been a strong influence in her life, as she has been in the lives of those she empowers, not least her daughters. Today, Fiona (33), a pediatric neurologist at Stanford, is married and expecting Mitchell’s first grandchild; Megan (30) went to Wesleyan University and is now a zoologist at the Fort Worth Zoo. Mitchell herself was in the first generation of her family to attend college.

When we meet in her Stamford, Connecticut office, she is welcoming, calming, and puts me at ease with the small trace of her mid-century New York accent that still comes through in her long a’s. She is a manager without pretense and it shows in her candor, attributable, one suspects, to her Irish parents and the close community in which she grew up.

℘℘℘

Tell me about your childhood in New York.

My parents were pretty typical Irish immigrants. My father worked for the Transit Authority in New York. My mother stayed at home and wrestled with three kids. They were not formally educated, but understood the power of education and were very bright and well read. I went to local Catholic schools with a group of very young girls and many of us were on either partial or full academic scholarship. So we were always keeping up with each other.

I was a typical middle child in terms of being a little bit more anxious for independence. I went to the City College of New York, which was my idea of rebellion – a large public university – rather than follow my cousins’ path of going to a Catholic university.

What stands out about your relationship with your parents as a child?

There’s one memory in particular about my father that illustrates how I was raised. When I was very young I was attached at the hip to him. I would insist on going out for walks with him, but I was really little and couldn’t keep up. And I’d say “Slow down, slow down.” And he’d say, “No, keep up.” Upon reflection, it taught me it wasn’t just about keeping up, but pushing ahead.

What’s the most important thing they taught you that impacted your career?

Like so many American immigrants, my parents had an unyielding focus on finding success through hard work. I’ve carried that with me every day. In fact, as I progressed in my career, I developed a mindset that my success would be predicated on my ability to outwork anyone else.

And they led by example. When I think about someone emigrating from their homeland, it reinforces that fearlessness is the only path to achieving great things. I brought that attitude to being a woman on Wall Street, where I was definitely in the minority.

What about their connection to Ireland?

My father was a lobsterman and the lobsters were too precious to eat because they sold them to the hotels in Sligo – they couldn’t afford to eat them. But growing up, whenever we went out to dinner, which was not frequently, he always ordered lobster. In my eulogy for him, I recalled how, when I was young, I couldn’t figure out why he did that. But when I went to Ireland as a young person and gained the perspective that comes from a trip like that, I realized why it was so significant to him – and how it reflects the Irish experience in America and the value of opportunity.

My mother worked in England during WWII, and came over here on her own. Her mother died fairly young, and I think for her it was as if life started here. And she didn’t go home for a really long time; she was here for 25 years before she went home. I think people deal with loss in different ways, and my mother’s way of dealing with it was to just power through it. And powering through it meant saying, “My life is here in front of me and I move through it and move forward.”

There was a great sense of family and community that my parents had. The sense of knowing your neighbors to the extent you can, being helpful and having them as part of your life. My mother was a very social person and she had many friends from all walks of life. And I think that sense of curiosity about people has really shaped me.

As a child, did you have any idea of a career path?

It certainly wasn’t this. A good friend of mine who is CEO of a large asset management business told me once, “We weren’t raised to be investment professionals.” It was a world completely unknown, frankly, to my parents and me.

I made a lot of big leaps. It’s important to take risks and not be afraid to fail. The way I learn is through an immersive atmosphere that forces the issue. I had a couple of real pivots in my life. I tell this to my kids all of the time, “You don’t know where you will end up. You just have to be willing to embrace it when these opportunities come along.” When I went to Banker’s Trust I was singularly focused on succeeding, and I believe that perseverance emanated from my parents.

What attracted you to a career on Wall Street?

The career shift was the result of two things. First, I was drawn in by how energizing I knew the industry would be. The way things change so rapidly in markets and the demands of clients made this type of job very desirable – I knew it would always be interesting. The second thing was there was never going to be any uncertainty about your purpose and your contribution. Success and measurement were clear every day and I liked that a great deal. Then when I later came to GE, I was able to remain in the investment industry, but at the same time leverage the company’s larger worldwide footprint in numerous industries to expand the way I thought about the global marketplace.

How have you been successful in these roles?

Again, hard work and single-mindedness are especially critical, but there’s a lot more to it than that. As a woman in this industry, I learned to stand my ground and be tough, but I also learned to build strong relationships that I have to this day. In any industry, it’s important for women to build a personal brand, and that starts with the right partnerships with the right people who can advocate for your brand.

How do you think you’ve changed since you first started out on Wall Street?

I think more strategically. I think I’ve gotten a lot more patient. I think I’m a much better listener. And I have a great deal more empathy. All of those big

pivots in life make you realize that there are solutions to issues when you stop to reflect and be thoughtful about the challenges in front of you. There’s a sense of a longer-term view, listening to people and being confident in myself and my ideas and my questions.

How did you manage your long hours when your children were growing up?

We always had live in nannies. Everyone understood the expectations. From a pretty early age, I was very mindful around travel. I would tell the kids, “I will be here this day” and when I’d be back. I used to go to California quarterly, I had a lot of clients there, and my mother would stay with us. Generally holy hell would break out because I was less structured and she wasn’t. I would often say, “Listen, everyone in this house has a job.” I had an Irish nanny with us for a long time. All of us are still in touch. And her sister got married in my house. That’s the kind of relationships we had.

Do you have a management philosophy?

Because I love to own what I do, I like people to feel like they own what they do, too, whether it’s my assistant or my chief marketing officer. I’m here as a sounding board and, hopefully, a guide, with an integral and respected voice in the process. But in the end, ownership means getting the job done well and on time, whatever approach you take to executing the work.

Leadership is also about building teams, which is an area where I’m a strong proponent of emphasizing diversity, and the way that encouraging different perspectives leads to better outcomes. You want diverse role models around you. And I think in this industry we need to continue to find ways to tap into the leadership potential and capabilities of women.

I’ve always said to people, “Tell me why I’m wrong. Push back at me. I want to understand where the pitfalls are here.” That type of openness to being challenged is important as well.

What was it like to be at Bear Stearns when it failed?

I learned a lot. I really, really learned a lot. It was a tough time. It wasn’t the end of the world. What you thought was your future was not going to be your future and you had to recalibrate your life, which was not such a terrible thing. Because you can survive it and go on and do some pretty interesting things.

Anything you would change about the industry?

I would love to see us continue to be a more diverse industry. I would love to see women grow on the investment side of the

industry. And you can say the same in many other industries like technology. It comes back to understanding what’s possible and understanding that those positions are available. If you’ve got a young woman with great analytic skills, she can do any one of a number of things, and why not be an investor?

Tell me about your work with She’s the First.

It spoke to my mother’s background. It’s all about opportunity. When I was in Guatemala in January, I cried because I found the spirit of the girls was so extraordinarily courageous. We visited with families who didn’t speak Spanish – there are 24 native languages in Guatemala, so the first hurdle a kid needs to get through in school is to learn Spanish. A few other people and I spent time with one family up in the mountains and neither parent spoke Spanish. But I just saw the bravery of these people patching a life together, an economic life. It takes you out of yourself a bit.

I have a picture of where my mother was raised – a thatched cottage, very small – and it reverberated for me. It really stopped me in my tracks. These kids are walking down and up that mountain everyday to get to the bus to get to school. So it’s a real commitment to try and make this work for them. This family didn’t own any of the land that surrounded them; they just worked it. They wove and sold things locally. So it made you stop and think about what opportunities we had here.

Does being a child of immigrants influence your outlook on immigration today?

Absolutely. I say this all the time – I’m an American story. My kids are the result of an American story. They got to go to Wesleyan and Harvard and Stanford and places that were not in my worldview earlier in life. And I just think that the beauty of successful immigration is that it ripples. There’s more that one can achieve in this country. When I look at what helped my parents and my generation and my kids it was stability, jobs, the opportunity to work, and great access to education. With studying and hard work, there is a lot that is possible.

Thank You. ♦

Leave a Reply