Saturday, May 7 marks the 101st anniversary of the sinking of the R.M.S. Lusitania, the Liverpool-built passenger ship whose destruction sparked the United States’ decision to enter World War I in 1917.

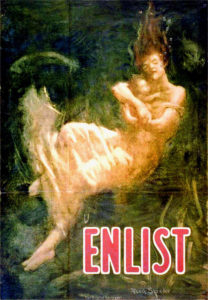

Just after two o’clock in the afternoon on May 7th, 1915, the luxury liner, heading from New York to Liverpool, was torpedoed by German U-boat 20, and then suffered a second, still unexplained explosion. The ship sunk in a mere 18 minutes, just 11.5 miles off the coast of County Cork, Ireland. Nearly 1,200 men, women, and children died, including 128 Americans. The American lives lost were crucial in the U.S.’s decision to enter the war, and indeed, many recruitment posters in the United States offered chilling reminders of the disaster.

Last year, for the centenary, a huge commemoration ceremony took place to in honor of the ship and its victimsin Kinsale, Co. Cork. Over 150 of the victims of the wreck were buried in the town’s Old Church Cemetery. The events lasted all day and were attended by nearly 10,000 people, including Irish president Michael D. Higgins, British ambassador Dominick Chilcott, American ambassador Kevin O’Malley, German ambassador Matthias Hopfner, and Irish Defense Minister Simon Coveney. A 2:10 p.m. whistle blast marked the moment at which the Lusitania was struck by the fatal torpedo one hundred years ago. Other events of the day included a minute of silence and a ceremonial wreath laying by the Irish president and the aforementioned ambassadors at the Lusitania Monument in Kinsale’s town square.

One of the most fascinating stories surrounding the ship regards a notification printed by the German Embassy in various American papers on April 22nd, 1915, little more than a week before departure. While the ad did not explicitly mention the Lusitania, it noted ominously that any passengers attempting to make an Atlantic crossing and entering Great Britain’s waters would be doing so “at their own risk.” Many chalked it up to wartime intimidation, and some, including the ship’s captain, William Turner, dismissed the notice as a colossal joke. Turner managed to survive the disaster, and it is likely realized the folly of his believing the threat to be “Berlin’s latest bluff,” as London’s Daily Telegraph had termed it.

Some historians believe that the second explosion, which caused the Lusitania’s rapid descent, was catalyzed not by a faulty boiler as some lab test have suggested, but by munitions being secretly ferried from the then-neutral United States to England. In this camp falls Gregg Bemis, an American venture capitalist who owns the salvage rights to the ship.

In the early 1980s, however, new maritime law extended national jurisdiction to 12 nautical miles off-coast, making the Lusitania just within Ireland’s domain.

A 1994 documentary vaulted the ship back onto the radar of the diving world, and that same year, a crew of divers, without Bemis’s permission, plundered the ship. Both Bemis and Ireland sued, and the divers eventually returned the purloined items to Bemis, their lawful owner, who donated them to Irish museums.

Despite the rather tidy end to this debacle, the Irish government began to worry that the Lusitania would fall victim to further looting, and quickly placed a protective order on the ship, which would make it necessary to obtain Ireland’s permission – in addition to Bemis’s – to dive there.

Bemis hopes to prove that the Lusitania was indeed carrying illicit arms and solve a great historical mystery, but in order to do so, he must make physical changes to the ship that the Irish government views as a historical artifact. The conflict between unearthing the ship’s true legacy and preserving the ship’s hull has led to a legal battle lasting over 20 years from which neither Bemis nor Dublin seems inclined to back down.

While we may have to wait for the true cause of the Lusitania’s sinking, the various myths that surround the ship are just as fascinating as those that follow the Titanic. (The sinking of the two ships, just three years apart, are considered the greatest maritime tragedies of the modern age, and despite the greater immediate impact of the Lusitania’s demise, the Titanic’s legacy has earned greater fame.)

Among the casualties on the Lusitania was art collector Hugh Lane, who was rumored to have been transporting original paintings by Rembrandt and Monet sealed in tubes, which have yet to be recovered (if the rumors are indeed true). The tantalizing prospect of almost $100 million worth of art hiding there on the ocean floor, not to mention the mystery of the second explosion, makes the Lusitania as intriguing as its ill-fated “sister,” the Titanic. (Although to this reporter’s knowledge no one has ever made a dramatic short about missing the Lusitania‘s final voyage due to alcoholism.) ♦

Sir Hugh Lane was definitely carrying the paintings. In a newly uncovered survivor account, Angela Papadopoulos describes Lane showing them to her during the voyage. Our book has this account. It is called “Into the Danger Zone: Sea Crossings of the First World War”. It is available on Amazon.

RMS Lusitania was built in Clydebank, Scotland – not Liverpool, England.