Historian Christine Kinealy wonders if the Irish national anthem is still relevant today.

℘℘℘

Soldiers are we,

whose lives are pledged to Ireland,

Some have come

from a land beyond the wave,

Sworn to be free …

Ninety years ago, as the newly created Free State was coming to terms with ten years of turmoil, which included war, civil war and partition, it simultaneously was trying to create an identity as an independent state. Challengingly, however, it was a 26 (not 32) county state, which had been coerced into accepting dominion status within the British Empire. Coins, banknotes, stamps, passports, postboxes were all to be rebranded to reflect this new status, while, on a macro level, issues of the national flag and national anthem were yet to be decided on. In the midst of this period of readjustment and renewal, a national anthem was selected. In the same way as the partition of the country had been, its hasty selection was regarded as a temporary solution to an Irish problem.

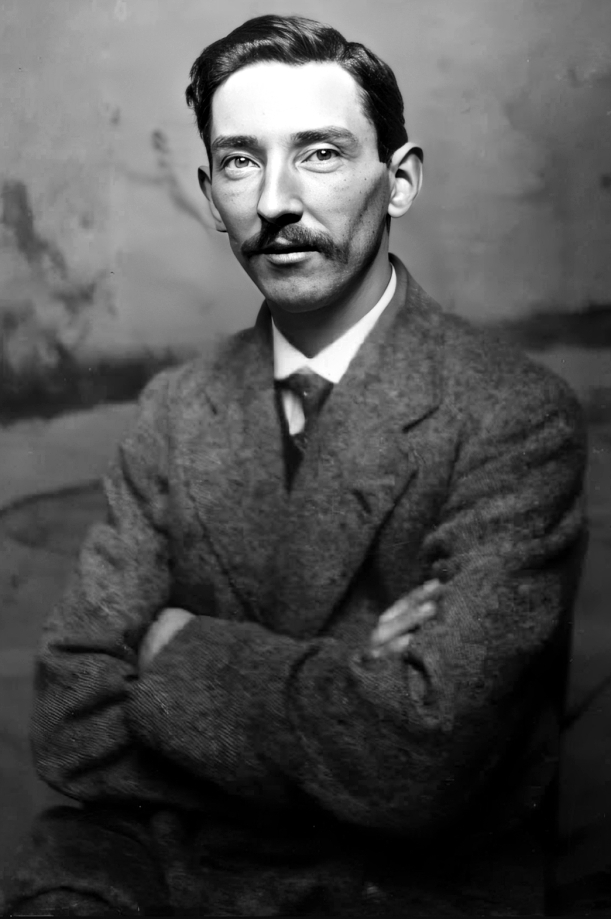

The history of the anthem reflects the troubled times in which it was born. The lyrics were written by Peadar Kearney (1883 – 1942), a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, probably in 1907, with the melody provided by his friend Patrick Heaney (1881 – 1911). The original lyrics, which were in English, were first published by Bulmer Hobson in 1912 in Irish Freedom, although Kearney was not mentioned as the author. The words and music were not published together until December 1916, some months after they had been sung by the insurgents in the General Post Office.

The song was popular with the Irish Volunteers, formed in 1913. It gained even more favor during and following the 1916 Rising; the idea of being soldiers, rather than rebels, resonated with the participants. Following the creation of the Free State, the song was increasingly associated with the army, although it was also sung at some sporting events.

Regardless of its popularity and republican associations, it was not until 1923 that an Irish translation was first published in the Freeman’s Journal and, a few months later, in the Irish Army’s publication, An t-Óglác. The translator, Liam Ó Rinn (1886 – 1943), had fought in the 1916 Rising, been imprisoned in Frongoch (an internment camp in north Wales), and later worked in the translation department of the Free State’s Oireachtas. In the article in the Freeman’s Journal, Ó Rinn (using his pen-name, Coinneach) rendered the chorus of “Amhrán na bhFiann” as:

Sinn Fein Fáil

atá fé gheall ag Erinn;

buíon dár slua

thar tuínn do raínig chughainn;

Fé mhóid veh [bheith] saor –

seanntír ár sínsear feasta

ní fagfár fén [faoin] tíorán ná fén tráill

Anocht a theum sa bhearna bhaeil

Pé olc maih é, le grá do Ghaeil.

Le gunna-scréach, fé l mhach na bpléar

Seo liv! [libh] canaídh amhrán na bhFiann.

Although other translations were made, Ó Rinn’s, with some amendments, became the accepted Irish language version, quickly overtaking the English-language original in terms of popularity.

Despite the popularity of “The Soldier’s Song,” officially the Free State remained without a national anthem. At formal events, both in Ireland and overseas, the vacuum was filled with a variety of patriotic songs, the most popular being Thomas Moore’s “Let Erin Remember,” T.D. Sullivan’s “God Save Ireland,” and Thomas Davis’s “A Nation Once Again.”’ Some newspapers hoped that the 1924 Olympics in Paris would be a catalyst for a decision, but no anthem was announced, although the Free State’s official song for the occasion was “Let Erin Remember.” The uncertainty was evident two years later at the TT Races (popular road races) in the Isle of Man, when Irish riders were greeted with random extracts from “St. Patrick’s Day,” “The Minstrel Boy,” or “Come Back to Erin.” The GAA, meanwhile, was increasingly adopting Ó Rinn’s version of “The Soldier’s Song.” Clearly, there was no consensus on a national anthem. In contrast, Unionists in the Free State and elsewhere, continued to sing “God Save the King” at public events.

In the face of government inertia, an Irish newspaper intervened. In 1924, the Dublin Evening Mail hosted a “A National Hymn to the Glory of Ireland” competition. A prize of 50 guineas was offered and a panel of judges, which included the Nobel prize-winning poet, W. B. Yeats, was convened. Embarrassingly, none of the submissions were deemed to be worthy and, perhaps even more damningly, the paper reported that “Most of the verses submitted to us were imitations of ‘God Save the King.’” The competition was reopened in March 1925. A winner was announced, but she and her song (the uncharismatic, “God of Our Ireland”) immediately disappeared from view. What the Mail’s intervention had done, however, was to keep the issue in the public eye, while demonstrating that finding a new national anthem was not going to be easy.

The matter was brought to a head in July 1926 when the Minister of Defense, Peter Hughes, was questioned in the Dáil by a backbencher, Sir Osmond Esmonde, about the status of the national anthem. Esmonde had first directed the question at the President, W. T. Cosgrave, but had been told that this was inappropriate. Hughes – amidst much laughter – responded that the Irish national anthem was “The Soldier’s Song.” However, he qualified his statement by adding, “at present.” Hughes’ unilateral pronouncement was not without demur. An editorial in the Irish Examiner admitted their “surprise” at the minister’s statement, adding:

“‘The Soldier’s Song’ has a bold air, and it is associated with some stirring episodes in the latter-day history. Something more is wanted … The nation itself will make a choice sooner or later, and it is too soon to say that the decision has been made by the Free State.”

Nonetheless, endorsement for this choice came from the newly established Radio Éireann, which used the anthem at its close of broadcasting each day. The song also had the backing of the Free State Army and the GAA.

In 1929, the government authorized German-born Colonel Fritz Brasé, founding director of the Irish Army School of Music, to write a suitable arrangement for “The Soldier’s Song,” but for the chorus only. Interestingly, only the chorus (not the three stanzas) was regarded as the national anthem. Even more strangely, perhaps, the state argued that the title and the music alone – but not the words – constituted the Irish national anthem. This argument was made public in 1933 when Peadar Kearney threatened to sue Radio Éireann and others over their failure to give him royalties – at this stage, Kearney was making a modest living as a house painter. Heaney had died in poverty at 29 and had been buried in a pauper’s grave in Drumcondra Cemetery. The state responded to this challenge by acquiring copyright from the estates of Kearney and Heaney for £1,000. Due to a change in law, copyright had to be purchased again in 1965, this time for £2,500. The copyright officially expired on December 31, 2012, 70 years after Kearney’s death. Interestingly though, only the English language version – and never the Irish one – was ever copyrighted.

In 1937, 30 years after Kearney had first penned “The Soldier’s Song,” the Free State government adopted a new constitution. Its conservative pronouncements – particularly on the status of women – was an anathema to some of the foot soldiers of the Irish Revolution. While it confirmed Irish as the national language, endorsed the name of the state as Éire, and ratified “the tricolour of green, white and orange” as the national flag, no reference was made in the document to a national anthem. Despite being ignored, in the decades that followed, the chorus of “Amhrán na bhFiann” became more firmly embedded in the social, sporting, and cultural life of the nation.

In the decades since the passing of the 1937 constitution, Ireland has undergone many changes, including the Free State becoming a Republic in 1949, thus formally ending its long and tortuous relationship with the British Empire. Throughout these political and constitutional transformations, “Amhrán na bhFiann” has continued as the anthem.

The early history of “The Soldier’s Song” and its adoption as the national anthem was partly a microcosm of other tensions and conflicts taking place in Ireland in the early 20th century. After 1922, the fledgling 26-county Free State sought to create a distinct identity while healing some of the wounds of centuries of conflict with Britain, and, even more painfully, the wounds and fissures of a recent war that had pitted comrade against comrade and brother against brother. “The Soldier’s Song,” with Kearney’s defiant lyrics, and the rousing chorus, suggested that the sacrifices had not been in vain, because the Gael had triumphed over “Saxon foe.”

For others though, the song’s overt militarism and factionalism are anachronistic and increasingly out of place in a progressive democracy that is committed to neutrality and, since 1998, been a model for peace processes in the world. These apprehensions had been articulated during the early stages of the peace process. A 1995 report from the Forum for Peace and Reconciliation, when acknowledging the fears of the Unionist community and obstacles to reconciliation, suggested that the Republic should choose a new national anthem that was not “excessively militaristic.”

Within the Republic also, there have been periodic calls for a new national anthem. In the 2011 Presidential election, two of the seven candidates admitted that they would be willing to change the anthem. Michael D. Higgins, the eventual winner, when asked if the national anthem was still fit for purpose, responded that if it was written today, it would be different.Nonetheless, in 2016, “Amhrán na bhFiann” remains in place. Both the English and Irish versions appear on the Taoiseach’s official website and, when the President arrives at an official engagement, the first four bars of the anthem are played, immediately followed by the last five.

The adoption of “The Soldiers’ Song” as the national anthem took place almost by accident, with no public debate, no consensus, and not without some controversy. As the decade of commemorations unfolds and we reflect of the legacy of Easter 1916, perhaps it is time to reflect on Ireland’s 90-year old national anthem and ask how appropriate is it in 2016? Is it time to say goodbye? ♦

_______________

Professor Christine Kinealy is director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University. Her most recent publication is The Bad Times / An Drochshaol (with John Walsh), a graphic novel about the Great Hunger set in Co.Clare.

I think an entirely new national anthem should be written.