A grandmother’s letters, passed down through two generations, offer a fascinating, and at times intimate, glimpse into the period following the 1916 Rising. Dermot McEvoy talks to Rosemary Mahoney

“My maternal grandmother, Julia Frances Rohan (née Fraher), and her five sisters who emigrated to Boston from Ballylanders, County Limerick, were fervid Sinn Féiners. My grandmother Julia was perhaps the most fervid of all,” recalls the writer Rosemary Mahoney (For the Benefit of Those Who See and Whoredom in Kimmage).

“My grandmother’s family was already highly politicized by the time of the Easter Rising. She was a member of Cumann na mBan, donated money to the Irish National Volunteers to help them buy arms, and campaigned at all the Boston meetings for an independent Ireland. She knew everybody in Boston who was fighting for the cause. Many who were involved in the Easter Rising, in one way or another, stayed at the Fraher house in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Julia was in her mid-twenties at this time and not married yet.”

The list of those who stayed at Julia’s house reads like a “Who’s Who” of Irish revolutionaries. Diarmuid Lynch a Sinn Féin member of the First Dáil who helped plan the Rising, and Liam Mellows, also a Republican and a Sinn Féin politician, were house guests, as was MM (Min) Ryan, who hailed from a strongly nationalist family, and was the girlfriend of Seán MacDiarmada who was executed for his part in the Rising. Ryan later married Richard Mulcahy, former Chief-of-Staff of the IRA and the man who replaced Michael Collins as head of the National Army in 1922.

Nora Connolly the daughter of James Connolly, the labor leader who was shot for his part in the Easter Rising of 1916, and her friend Margaret Skinnider, one of the few women who fought in combat on Easter Monday, were also visitors and friends of Julia’s.

Nora wrote to Julia in July 1917 from her apartment on Vanderbilt Avenue in Brooklyn and her homesickness for Ireland is obvious from her letter: “It was just a year ago that I left Mama and got away. It seems years now.” Maybe her homesickness had something to do with her opinion of New York: “New York is an ugly horrible place. Anyone who prefers New York to Boston must be mad.” Connolly goes on to mention Éamon de Valera’s victory in the Clare by election: “Margaret [Skinnider] and I were at the Irish World office yesterday and were told that de Valera had won the elections 3 to 1. The figures were 5000 odd to 2000 odd.”

Nora goes on to dig into John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party who had urged Irishmen to fight for Britain in the Great War in the hopes of strengthening the case for Home Rule. Redmond’s brother Willie had been killed on the Western Front prior to the election, but as Nora points out, that sad fact did not win any votes over to Redmond. “[de Valera’s victory] shows how much Clare is grieving for Willie Redmond,” she writes. She then pivots to mention a mutual friend and fellow Sinn Féiner: “I saw Liam Mellows on Monday. He is looking well but horribly Yankeefied,” she comments.

In August Nora wrote again, voicing a common summer lament from Irish immigrants: “I cannot write to you now as much as I would wish because I am simply dying with the heat.” On a more serious note she laments the death of Muriel MacDonagh, wife of 1916 patriot Thomas, who was drowned in a swimming accident: “Wasn’t that dreadful news about Mrs. MacDonagh? Just think of the two little ones left without father or mother.”

In June 1918, Nora was heading for home to Ireland and was obviously worried about German U-boats: “Dear folks won’t you pray that we reach home safely,” she writes and she adds a bit of Fenian gossip also: “Mrs. [Hanna Sheehy-] Skeffington is sailing on the same boat.”

Nora Connolly returned to Ireland where she was active in Cumann na mBan activities. She went against the Treaty, which brought the Irish War of Independence to an uneasy end in 1921 and ultimately led to the partition of Ireland into present day Northern Ireland and the 26-county Republic. During the Irish Civil War between pro (led by Michael Collins) and anti-Treaty sides (led by Éamon de Valera), Nora was active in socialist and union activities and in 1957 was appointed to the Irish Senate by De Valera where she served for 12 years. She died in 1981 at the age of 88.

M M Ryan’s letter, mailed in Boston and dated February 1, 1919, shows the cracks in the American Fenian movement:

Dear Miss Fraher,

I came on here yesterday and hope to see you before I go back to New York. I am recovering from an attack of “flu” and have just been on my feet but a few days. Yesterday I received a special delivery letter informing me of the illness of my sister Katherine [Mary Kate, known as “Kit”] so I came on. She is suffering from a nervous breakdown but is better than I expected to find her. I am anxious to know how your brother is. Are you going to the convention? [The Irish Race Convention, held in Philadelphia on February 22-23, 1919] Yours truly has not received an invitation from the patriotic National Secretary [believed to be Diarmuid Lynch who was the National Secretary of the Friends of Irish Freedom, the people who ran the Race Convention]. We don’t like each other. I feel about him as Nora Connolly did. He is a narrow minded fellow—a good tool in the hands of The Judge [believed to be prominent Judge Daniel Cohalan, an associate of Lynch]. A fine henchman. But Liam [Mellows] is every inch a man! They can’t use him and the men and women who went home know it and carried the news home. Mrs. S. S. [Sheehy-Skeffington], Nora, and Margaret [Skinnider] had the “ladding” [this word is unclear] lights here all measured and they won’t be able to “put it over” the men at home. I hate [word hate is double underlined] the Judge and when everything is all over I’m going to attack him publicly.

Liam Mellows wrote to Julia in April 1918, and is delighted about the news from Ireland: “Everything at home looks well. It’s laughable to see the hierarchy advocating strikes & John Dillon embracing Sinn Féin.” He celebrated a special anniversary: “Do you know that today is the anniversary of the beginning of that week in 1916? I see by a paper from home that Galway was ablaze with bonfires on Easter Saturday night. That’s grand.”

In June, Mellows (who signed his letters in the Irish: “O’Maeliosa”) offers his condolences to Julia on the death of her mother, but the discussion soon turns to brutal politics: “Well, God rest her soul. Who knows but that it is all for the best. She would feel so bad if she lived long enough to witness the trying—indeed terrible times—that are coming. God help us all & give us the courage & faith to endure & the people at home the strength to suffer, for we are on the verge of impending & terrible events. But we can win. That I do not doubt. To doubt it is to lose & we cannot lose for the hand of God is with us & He can triumph over the poor efforts of mortal men.”

By August there is a familiar Irish lament in Mellows’ letter: “It must be the heat, and sure that is enough to drive anyone—like the cows in summer with the gadflys—mad.” But the talk soon turns to politics and the dreaded threat of conscription: “The people at home are sticking [or striking] out well, but they expect Conscription the end of October, then—God help us all.”

By January 1919 Mellows was living on West 96th Street in Manhattan and worried about influenza and pneumonia that was striking family and friends on both sides of the Atlantic. But politics was always in the forefront of his mind as he mentions being elected in absentia as a TD to the first Dáil: “Everything goes well in Ireland—the spirit is wonderful, as the results of the election has shown…You will see by it that your humble servant has been elected to two seats [Galway East and North Meath]. The whole thing came as a surprise to me; unsought and unwanted. God give us all the strength, wisdom, & principle to do what is right.”

He writes of his adventures at the White House: “Diarmuid [Lynch] and myself paid a visit to Washington six weeks or so go and called at the White House to see the President [Woodrow Wilson] to present a demand from the people of Ireland for representation at the ‘Peace’ Conference. His Lordship was not home, but we left the ‘scrap of paper’ and bowed ourselves out of the august presence of his secretary’s secretary. Some style, eh!” His spirits remain high: “As the Yanks in New York say—‘Safety foist.’ ”

In August 1919, Mellows was living at 220 East 31st Street in Manhattan and was congratulating Julia on her marriage to Michael Rohan: “I hope you are happy in your new home and that Michael is as kind and loving a husband he was before the great event in Boston.” But the letter quickly turned political: “The President [Éamon de Valera] will speak in Baltimore but I don’t know exactly when as his tour is not yet mapped out completely. He returned from California yesterday delighted with the result of his trip.”

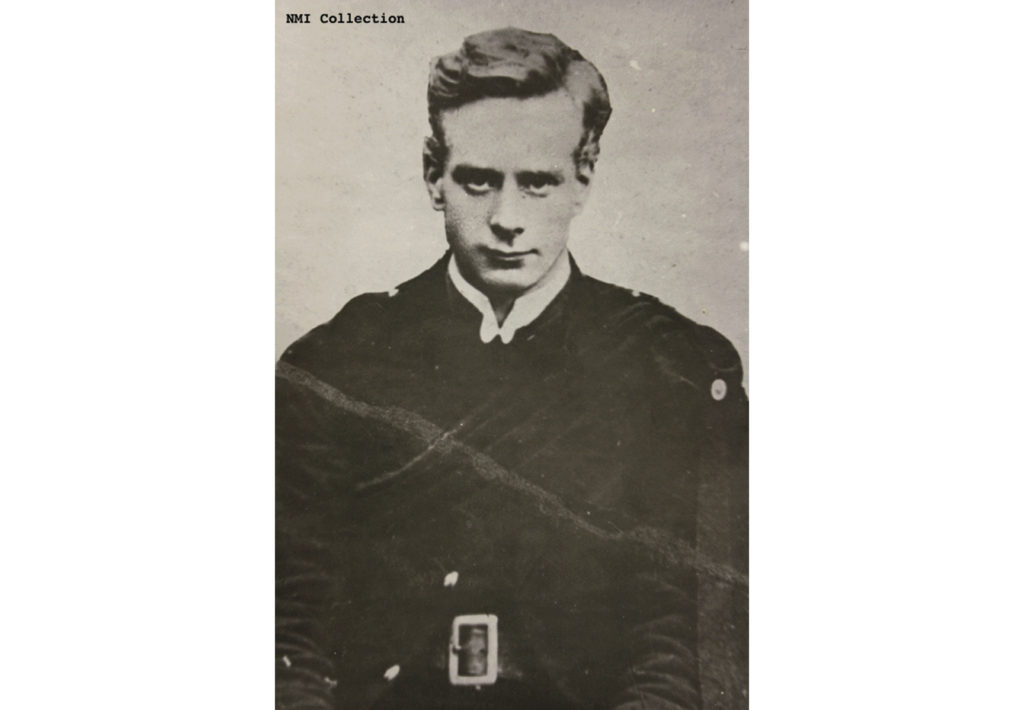

Mellows led men in the west during the Rising and escaped to New York where, for a time, he was jailed for his support of Germany during WWI. In April 1918, with the conclusion of the war, Mellows returned to Ireland and became the Director of Supplies for the IRA during the War of Independence. He went against the Treaty and was captured when the Four Courts in Dublin fell to Pro-Treaty forces. Jailed, he was executed in December 1922 by the Free State government in retaliation for the murder of TD Seán Hales, which he played no part in.

℘℘℘

465 Vanderbilt Ave

Brooklyn, New York

July 12th [1917]

Dear Julia,

I hate writing letters to anyone I like: I feel so far away when I do. I have not yet started to hunt for a job yet. The Colums on whom I was depending to take me around are out of town, also my friend at the Review of Reviews. But I will write to Frank Harris and see what he has to offer. He told me to call on him when I came to New York.

I’m so homesick Julia for you all. I really & truly felt as if I were leaving home again. It was just a year ago that I left Mama and got away. It seems years now. And now I feel almost as much alone at leaving you as I did when leaving her.

New York is an ugly horrible place. Anyone who prefers New York to Boston must be mad.

I had a letter from the Public Library in Boston asking me to return the books. Did Sean [John O’Donnell] not have a chance to return them yet? There will probably be some money due on them now.

Margaret and I were at the Irish World office yesterday and were told that De Valera had won the elections 3 to 1. The figures were 5000 odd to 2000 odd. That shows how much Clare is grieving for Willie Redmond [Irish politician.]

I think that everything is coming as we would like it to. I was speaking to a man who arrived last week from home. He was on the ship with all the prisoners when they were returning to Dublin [1916 rebels who had been imprisoned in England.] He said they were amazed and delighted at the change of public opinion. I had a letter from Mama this week. She said she was in great excitement waiting the return of her boys.

Julia I’ve lost my Tara brooch again. Amn’t I unfortunate?

I saw Liam Mellows on Monday. He is looking well but horribly Yankeefied. I really have not a thing to write to you about. But please goodness I won’t always be so.

Best love to Mrs. Fraher, Lizzie, Sean & yourself.

Remembrances to the “right sort.” [Michael Rohan, my grandfather, who was courting Julia then.]

Very sincerely yours,

Nora Connolly ♦

Thanks for the article – and free to read, too! Interesting. Nora is such a beautiful name. They say the Greeks and the Irish, of all peoples, have written the most songs about their homeland.

Love to all,

Peter Garland

Oakland, Ca (from Dublin. We have a Dublin here, too. My love lives there!)

Enjoyed the letters very much. My GGF was Edmund Fraher who was married to a Julia Meara. They were living in Ballinlough, Co Limerick in 1841 when my GGF Daniel was born. The family with 5 children emigrated to NY in 1853 and ended up in Chicago in the 1870’s.