Leading historians reveal the American story behind Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising with new books and exhibitions that explore America’s role in the Rising.

“No people ever believed more deeply in the cause of Irish freedom than

the people of the United States.”

—President John F. Kennedy, Leinster House Dublin, June 1963

On April 24, 1916, carrying a new tricolor flag, a small group of Irish revolutionaries rallied around their Proclamation for independence. The seven radicals who signed the Proclamation were a vivid group of idealists whose collective dream of a free nation was the latest manifestation of an ancient yearning. Though all seven, and seven more, were executed by firing squad within clays of surrender, their action was the first step toward the birth of sovereignty. This ancient civilization would become a nation once again.

History emerges from the active memories of those who become its storytellers. According to Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, we create our future by crafting the narrative of how we wish to be remembered. This record is a conscious effort to become heroes in a good, even inspiring story. Professional historians are perhaps the ultimate storytellers, charged with the responsibility for instructing current and future societies on which stories deserve to be told and remembered. Historians shape the public imagination and order the public memory of events long past. Such a revolution in remembering is happening today, as historians are retelling the story of Ire land’s Easter Rising of 1916 during this the centennial year.

During the century since the Rising, historians have reassessed the central cast, creating an historical ·consensus on the American affiliations these players shared. Until recently, the story of the Easter Rising has been told as a Dublin City pageant, with Clarke, Pearse, Connolly, MacDiarmada, McDonough, Plunkett and Ceannt as its heroes, carrying banners and marching to their executions. Today, that picturesque tale has yielded to a narrative whose complexity is energized by an emphasis on their American connections.

In this new, layered telling of the story, the revolutionary activity of the signatories was nurtured by their connections to the Irish-American community. Five of the seven were either citizens of the U.S., lived in America, had family in the States or, in Eamon de Valera’s case, was born in New York.

American support for Irish independence was problematic for the British, who sought a commitment from President Woodrow Wilson in the erupting war with Germany. One of the leaders, Sir Roger Casement, captured on Good Friday before the Rising, was executed several months later for his part in the rebellion.

The swift decision by the British government to execute the now-famous leaders of the Rising served not to remove the threat to the Empire but rather made martyrs of them. With blood on their hands, the British executioners in clue time were denounced for their atrocities in the world’s media led by The New York Times. Journalist / poet Joyce Kilmer covered the story intensely, contributing to the Times general coverage of the First World War that won the paper its first Pulitzer Prize.

The story of the Rising has evolved, both as it happened and as it is remembered. The seven key revolutionaries, five of whom were published poets and playwrights, knew the importance of the narrative and housed their headquarters in Dublin’s General Post Office, the center of the county’s communications. From the moment it happened, the story of the rebellion was told and retold.

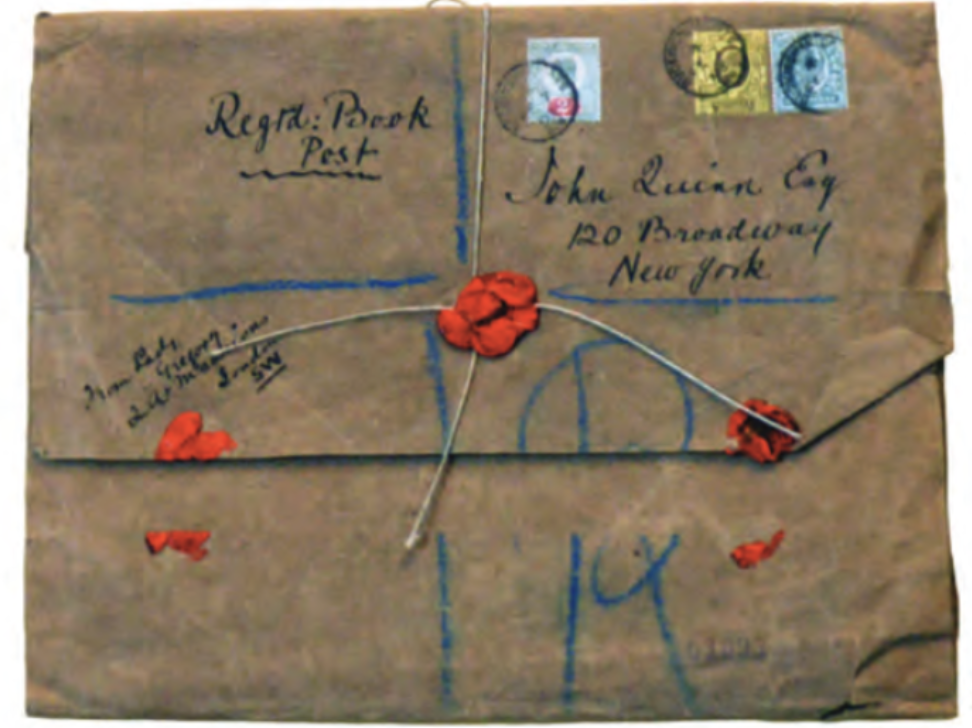

In his book The Insurrection in Dublin (featured in a new exhibition in Dublin’s National Gallery of Art), the author James Stephens reports his clay-by-day account and personal experiences of Easter week. The book, one of the first books about 1916, has since become a seminal chronicle of the Rising. Pages from the original manuscript, on view in New York’s Morgan Library, highlight real-time reporting of the events.

Through the years many writers have told the story, including the doomed leaders themselves, who left behind notes and letters. Many of these are on view in a brilliant online exhibition from the National Library of Ireland. Now, in the year of the centennial, the remembering has intensified. Six new books by contemporary historians highlight the American connection and enhance the remembered history of the Rising by acknowledging the role of America.

Terry Golway’s acclaimed 1999 biography, Irish Rebel: John Devoy and America ‘s Fight for Ireland’s Freedom, has been revised and reissued by Merrion Press. The importance of Devoy must not be underestimated, says Galway, who depicts him as a skilled tactician with unwavering dedication to Irish independence. Exiled from Ireland in the mid-1800s, Devoy made New York his base of operations. These included organizing a dramatic rescue of Fenian prisoners from Australia, rallying Irish America behind the Land War, serving as middleman between Sir Roger Casement and the German government, and driving Irish-American opinion. When he died in 1928, Devoy was accorded a state funeral and hero’s burial in Ireland under a tricolor flag.

Galway, a journalist and historian, explores the legacy of the Famine, which inflamed the ancestral drive for Irish independence in Ireland and America, where key p layers seized opportunities to advance their cause. At seizing opportunities, Devoy was unparalleled, staging a public relations coup with the funeral of Fenian rebel Terence Bellow McManus in 1861. New York Archbishop John]. Hughes officiated at the funeral Mass and in an impassioned eulogy that echoed in Ireland, Hughes said, “there are cases in which it is lawful to resist and overthrow a tyrannical government.”

Devoy used the McManus funeral as the precedent for another explosive public funeral, that of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, whose remains were returned to Ireland for a pageant burial in 1915 – an event widely considered the trigger for the 1916 Rising. Recently a review in the Irish Times stated, “It should shock … the conscience of this nation that practically no one in Ireland can identify the man [Devoy] who bad a public life dedicated to Ireland spanning over 60 years and whom the Times of London… called “the most dangerous enemy of [the British Empire] since Wolfe Tone.”

In Ireland’s Exiled Children: America and the Easter Rising (Oxford University Press) Robert Schmuhl reveals the complexities of American politics, Irish-Americanism, and Anglo-American relations during and after WWI. His book focuses on four key players – John Devoy, Joyce Kilmer, President Woodrow Wilson, and Eamon de Valera – who used powerful language as a strategy to achieve their aims. The uniqueness of Schmuhl’s account derives from his examination of me reportage of the Rising; he looks at the ways journalists sought to drive public opinion and muster support for their cause through their words, both spoken and published. Professor Schmuhl is Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Chair in American Studies and Journalism at Notre Dame, and director of the John W. Gallivan Program in Journalism, Ethics and Democracy.

Schmuhl highlights the tension for those who rose for Irish independence in a Europe poised for war. Irish republicans bad long looked west for help, for good reason: the Irish-American population was larger than the population of Ireland, with familial ties on both sides. Irish exiles in America provided financial support and the inspiration of example: that life independent of England was achievable. Ireland’s “exiled children in America” were acknowledged in the Proclamation announcing “the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic.” April 24, 1916, was a poignant moment, for despite American support for the rebels, the U.S. was moving closer to joining the Allies in the war against Germany. For many Irish-Americans, loyalty to American war policy or Britain’s granting of Home Rule was a choice against their deepest desires.

The Easter Rising occurred at a moment of social redefinition for women in both Ireland and America. In her lively and provocative book, At Home in the Revolution: What Women Said and Did in 1916 (Royal Irish Academy), Lucy McDiarmid reimagines that moment when women were finding themselves amid rebellion.

At Home in the Revolution begins from the premise that women were involved. Prior to the Rising, women had organized themselves by forming groups such as Cumann na mBan, dedicated to the Republican cause. But the Rising was a viral sequence of events, and McDiarmid captures the atmosphere of spontaneous unity that characterized a time when “women’s civic position was in the process of altering.” The women-and the men with whom they rose – made it up as they went along. We learn of the “small behaviors” of women such as Boston-born Molly Childers that led to major consequence. We witness the delightful vignette of Catherine Byrne, who “jumped into the General Post Office of Dublin” on 24 April 1916. Women came in through the windows, entering the public square, declaring themselves ready for rebellion.

McDiarmid, Marie-Frazee-Baldassarre Professor of English at Montclair State University, follows a cast of characters some whose spirit of independence was energetic and heartfelt and others who were not. In his review for Irish America magazine, Adam Farley writes “As a study of women in 1916, the book is both situated within and outside of the discourse of feminism … at once a political study of shifting gender relations as well as a thoroughly researched, vivid, emotional, and often comic look at forgotten stories of the Rising that will ente1tain as much as it will enlighten.”

Thomas Francis Meagher, the clashing Irish orator who became a hero on three continents, roars to life in The Immortal Irishman: The Irish Revolutionary Who Became an American Hero (HMH). As told by Pulitzer-Prize-winning New York Times columnist Timothy Egan, Meagher’s story dazzles. The story is the stuff of fiction: as a young man in Ireland, Meagher was arrested after a fiery speech during the Great Hunger and sent to Tasmania. After his eventual escape, he made his way to America, where he assumed leadership of his brethren, whom he inspired with impassioned rhetoric to join the Union cause in the fight against slavery. After the Civil War he moved to Montana with his wife, where, as Acting Governor appointed by his friend Abraham Lincoln, he died in mysterious circumstances.

Egan calls him the “immortal Irishman” because his words endure. Exhorting the Irish, and Irish America, to remember, Meagher insists on drawing strength from Ireland’s broken past. “That burden of memory is our history, and we will not forget… the famine, we’ll not forget the centuries of oppression. And Meagher, even at his most joyous, would say that there’s a skeleton at this feast. That skeleton is that burden of memory.”

It has been said that great historians recognize the past as “shaped by vices and virtues of flesh-and-blood people.” The tale of Thomas Clarke, a naturalized U.S. citizen, told in historian Geoffrey Cobb’s Greenpoint: Brooklyn’s Forgotten Past (NBNH), affirms this statement. At age 25, Clarke, a recent immigrant to the U.S., was sent to London on a dynamiting mission that was hatched in a Greenpoint dentist’s office. Clarke and his comrades were betrayed and arrested. After serving fifteen years, Clarke moved back to New York to work for Devoy. He returned to Ireland in 1907, and was the first signato1y of the 1916 Proclamation. He is considered the father of the Rising.

Such intense attention on the Rising might not have continued long after the events of Easter Week without Sir Roger Casement, the focal point of world media interest. When he dedicated himself to Irish independence, Casement was already well known, knighted for his humanitarian work. From New York, with the help of John Devoy, Casement sought support from Germany and in 1915 went to Berlin to make an ill-fated arms deal; he was captured before he could call off the Rising. His capture came despite the presence of Capra in Robert Monteith, sent to Berlin to sec to his safe return; Monteith managed to escape. Charles Cushing, the American grandson of Monteith, is working to have his grandfather’s memoir, Casements Last Adventure, reissued. Casement historian Angus Mitchell has compiled and edited One Bold Deed of Open Treason: The Berlin Diary of Roger Casement 1914-1916, which has just been published by Merrion Press.

These new books, like those that preceded them, bring to life men and women who seized the moment to declare Irish independence. The players shared a goal and a spirit that echoes the primary values of American democracy. Schmuhl reminds us that Thomas Clarke, a naturalized U.S. citizen, occupies the first position on the list of signatories of the 1916 Proclamation and ”a narrative of U.S. connections to the Easter Rising comes full circle with several accounts identifying Diarmuid Lynch, ‘another naturalized American citizen, as the last person to leave Dublin’s General Post Office (GPO) when it was engulfed with flames following nearly a week of fierce fighting.”

Golway captures this Spirit for all as embodied by John Devoy. “By sheer force of personality and determination, he [Devoy] bad made Ireland’s cause a transatlantic crusade, enlisting American support on behalf of a small and strategically insignificant island in the North Atlantic. All the while, he asked of America only what America demanded of itself: genuine democracy and authentic republicanism. He never ceased to be disappointed. But he never surrendered.”

These new books about the Rising offer an opportunity to revisit and renew interest in the meaning of those events for Ireland and America. ♦

_______________

1916 Rising: Proclaiming the American Story, a photo exhibition featuring Americas links to the 1916 Rising, opens April, 2016. Supported by the Consulate General of Ireland / New York. For more information contact: info@turloughmcconnell.com.

Fine summary of and drawing together of the many elements that make up the rich contribution of Irish America ,past and present. Very useful introduction to the current commemotations but also a ” who is who ” in Irish American historical studies. Thank you very much from an interested novice!

This article reminds me of a story I read many years ago about a group of A.O.H. men from the U.S. , few if any of whom had military experience, hat participated in the 1916 Rising. According to the story, Pearse would have preferred to have done without this rather pathetic ‘unit’, but he found a place for in his plans. This account is in a book on the Rising, but I have forgotten the title of this historical book.