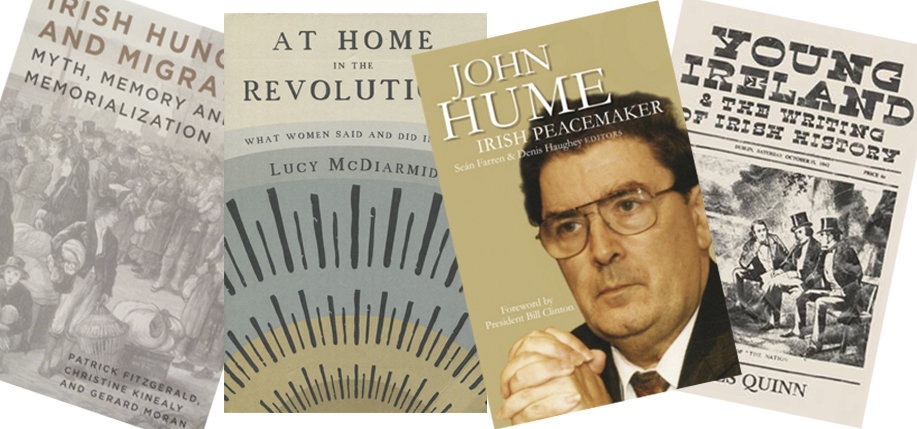

Irish Hunger and Migration: Myth, Memory and Memorialization

Edited by Patrick Fitzgerald, Christine Kinealy, and Gerard Moran

The biennial Ulster-American Heritage Symposium, which explores Ulster’s connections with the United States, celebrated its 20th anniversary at two venues in 2014: Quinnipiac University in Connecticut and the University of Georgia in Athens. Since 1976, venues have alternated between sites in Ulster and North America. The 2014 U.A.H.S. also marked 20 years since the sesquicentennial of the Great Hunger. Over the past two decades, Famine scholarship has incorporated new perspectives and disciplines, including migration studies, that have reinterpreted one of history’s, and Ireland’s, great tragedies.

This year, Quinnipiac University, home of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute and Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, published the proceedings from both 2014 conferences. This book, the third such publication of U.A.H.S. proceedings, gathers the work of 14 experts in the fields of famine, migration studies, and memory studies. The contributors to this volume are Marguérite Corporaal, Patrick Fitzgerald, David Gleeson, Christine Kinealy, Jason King, Brian Lambkin, Mark McGowan, Gerard Moran, Kay Muhr, Maureen Murphy, Andrew Newby, Nini Rodgers, Catherine Shannon, and Damian Shiels.

This collection of essays presents some of the findings of recent scholarship and considers the Great Hunger in an international and interdisciplinary context. These studies examine aspects of famine and migration in a broad chronological and geographical framework. They also address the process of memorialization, notably the roles of memory and myth. The result is testament to the importance of the ongoing examination of the bonds between Ulster and America.

Irish Hunger and Migration: Myth, Memory and Memorialization is edited by Dr. Patrick Fitzgerald (Mellon Centre for Migration Studies), Professor Christine Kinealy (Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute, Quinnipiac University) and Dr. Gerard Moran (European School, Lacken, Brussels).

– Turlough McConnell

(Quinnipiac University Press / 198p / $35)

At Home in the Revolution: What Women Said and Did in 1916

By Lucy McDiarmid

Lucy McDiarmid’s contribution to the study of the Easter Rising in its centenary year has been five years in the making, and it’s paid off. An American academic, McDiarmid focuses her keen scholarly tools on unique, alternate, and colorful moments in history that typify larger claims about cultural politics.

At Home in the Revolution, her most recent work towards this aim, at its broadest, is a study of changing gender norms at the time of the Rising. But more excitingly, it does this through a rigorous study of women’s words, ideas, and actions at the time that spans class, levels of political involvement, and political leanings – she gives a voice and a platform to just about every woman who wrote something about the Rising as it was happening, from the famous like Kathleen Clarke and Countess Markievicz to working class wives who kept diaries.

To do this, she uses diaries, letters, eye-witness statements, military pension applications, and autobiographies written by loyalists, nationalists, suffragists, women who fought at the G.P.O., and women who didn’t leave their home and wrote of tennis season beginning with the same interest as they documented news of James Connolly being shot. That means that this account of the Rising necessarily focuses on alternate stories of the Rising, often in minute detail (e.g. using bayonets as cooking utensils), delivered from unique and previously un-studied perspectives, giving McDiarmid the first opportunity to generalize the significance of these accounts that other historians have ignored. It is the skill and incisiveness with which she does this that gives the book its force.

As a study of women in 1916, the book is both situated within and outside of the discourse of feminism. To apply contemporary notions of the term to these women’s writings would be anachronistic, and yet not to situate their accounts within the context of gender (as in contemporaneous questions of unmarried women dressing a man’s wounds around his genitals) would elide the fact that these are stories of Irish women and men negotiating space at a time, as McDiarmid writes, “in which gender roles are uncertain.”

The book is at once a political study of shifting gender relations as well as a thoroughly researched, vivid, emotional, and often comic look at forgotten stories of the Rising that will entertain as much as it will enlighten.

– Adam Farley

(Royal Irish Academy / 300p / €25)

John Hume: Irish Peacemaker

Edited by Séan Farren and Denis Haughey

John Hume was inarguably one of the greatest Irish peacemakers and politicians of the late twentieth century. If this point has not already been made clear by his political career or the fact that he is the only person to have won the Nobel Peace Prize, the Gandhi Peace Prize, and the Martin Luther King Award, then this new book about Hume’s life and legacy as a peacemaking politician should.

Edited by Hume’s colleagues from the Northern Irish nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party, John Hume: Irish Peacemaker brings together a number of chapters written not only by noted political scholars, but also by the people who worked and lived alongside him, as well as offering a forward by former U.S. President Bill Clinton. Together they detail the various phases of his admirable life. To mention just a smattering of remarkable achievements discussed in this book, the reader is offered well contextualized insights into the beginnings of his career in the 1960s in the credit union movement, and carries on through his role as a civil rights campaigner and an S.D.L.P. politician, to his famous initiatives with Gerry Adams that culminated in the creation of the Good Friday Agreement.

The inside view afforded by the authors’ expertise and first-hand experience has its merits, especially for those who seek a volume on Hume that provides accounts rich in detail and intertwined with personal narrative. However, it can make for dense reading at times, demanding more than a casual riffle from the reader. Although a book like this – written and edited by the peers of a still living and much celebrated leader – runs the risk of sycophancy, its analysis manages to emerge on the side of objectivity while still providing the sound reasons for the celebration of Hume’s dedication to creating a just society and finding a lasting peace in Northern Ireland.

– R. Bryan Willits

(Four Courts / 240p / $35)

Young Ireland and the Writing of Irish History

By James Quinn

James Quinn’s refreshingly impartial Young Ireland and the Writing of Irish History shines a much needed lens on the legacy and impact of the Young Irelanders of the 1840s. Straightforward and unpretentious – a rarity for academic history books – Quinn unravels the early beginnings of The Nation newspaper and its charismatic and passionate staff, headed by Thomas Davis, Charles Gavan Duffy, and John Blake Dillon. It quietly went from a campaign for repeal that coalesced nicely with Daniel O’Connell’s nationalistic campaign to quickly become a popular source for Irish education, ballads, and most importantly, history. The Nation tapped into the widespread romanticism of the time. Taking as inspiration the German Romantics, they sought to make the past alive again, imbuing Irish history with heroic tales of grandeur and resurrecting past giants like Theobald Wolfe Tone and Hugh O’Neill. As Quinn explains, history became a source of pride and nationalism, which many Young Irelanders saw as needing release from the shackles of imperialist British ideology that portrayed Ireland as a defeated country. Quinn, however, is quick to balance his assessment of Young Ireland referencing their propagandist and polemical language mixed with their weak historical research, noting, “The Nation’s writers considered it more important that historical works be lively and inspiring rather than comprehensively researched.”

Comprehensive research is one thing clearly on display throughout Young Ireland. While biographical sketches of the main players are provided in the notes, Quinn does a remarkable job of recreating Thomas Davis, arguably the heart and soul of The Nation. Davis is perhaps the most widely quoted, but one does wish that other players were brought to the table. Duffy and John Mitchel play greater roles after Davis’s death, but there is a lack of examples from other contributors, particularly women who played an equally important role in The Nation’s success. Quinn does reference the role of women, albeit briefly, describing the verses of Ellen Downing, Mary Patrick, and Jane Elgee (mother of Oscar Wilde), writing, “the pithy and emotional nature of verse was regarded as more fitting to women than the laborious task of writing history.” Much of this may have been owing to the relative conservativeness of many of the Young Ireland leaders.

While slim in parts and repetitive in others, Quinn’s history gives a much-needed boost to Young Ireland historiography, a portion of which features remarkably in the concluding chapters. Quinn does a brilliant job of uncovering the legacy Young Ireland left behind and the influence that leaders like Davis, Duffy, and Mitchel had on later generations of writers, like W.B. Yeats, Arthur Griffith, and Pádraig Pearse.

In the end, Quinn proves that, while largely forgotten today, the historical and cultural impact of Young Ireland shaped the future and memory of Irish nationalism.

– Matthew Skwiat

(UCD Press / 236p / €30)

Leave a Reply