The trade union movement in America played a major role in Ireland’s struggle for freedom. But Irish rebels also played a significant role in building the American trade union movement, writes LiUNA general president, Terry O’Sullivan.

℘℘℘

The centennial of the Easter Rising carries a special meaning for proud Irish Americans, and especially for those, like me, who work in the American trade union movement.

That’s because Irish Americans view Ireland’s cause as our cause. And that’s not just because we’re Irish. And it’s not just because we share the same values as Irish republicans. It’s because, for more than 150 years, Irish Americans have played critical roles in the ongoing struggle for a free, united, and independent Ireland.

For decades, Irish Americans have raised money, smuggled arms, and traveled back to their ancestral homeland to support the cause of Irish independence. And the relationship hasn’t been one sided. From the earliest days of the American trade union movement, our Irish American labor leaders have borrowed ideas and used tactics they learned from the Irish republican movement. It’s always been a symbiotic relationship: American trade union leaders spent time in Ireland, Irish republican leaders spent time in America, and both campaign and organize for dignity and justice. The cross-pollination between the American trade union movement, the Irish labor movement, and the Irish republican movement has been so extensive that it is hard to imagine any one of the three without the others.

When James Connolly, union leader and Irish revolutionary, wrote that, “the cause of labor is the cause of Ireland; the cause of Ireland is the cause of labor,” he wasn’t being rhetorical; he was stating facts. From the earliest stirrings of land reform, from rent strikes and land agent boycotts to the Dublin Lockout of 1913, the struggles of working people, and the struggles of Ireland, have been one and the same. Few other revolutions in human history have been so intertwined with, and have owed so much to trade unions, as the Irish Rising. While our Irish brothers and sisters celebrate the well-known connections between Irish Labor Unions and the Irish Revolution, we in America celebrate the equally important, but lesser-known, connections between American Unions and the Irish Revolution.

The United States became a destination of choice for Irish immigrants because it promised religious liberty and social mobility. From the middle of the 19th century on, it became home to one of the largest Irish communities outside of Ireland. It also became one of the chief destinations for Irish Republicans fleeing from, or exiled by, the British colonial authorities.

But, even as Irish immigrants relocated their families, possessions, and lives to these shores, their hearts and souls often remained in the Irish counties where they had been born. They passed this love of country and community on to their children and grandchildren, and created a strong emotional and spiritual bond to their ancestral homes. (In my own case, while I deeply love the country of my birth, and am proud to be an American, I have always also considered myself a Kerryman, because my grandfather came from there).

Such powerful bonds to their homeland spurred Irish-Americans to remain directly involved in the ongoing struggle for Irish independence throughout their lives. And, because so many Irish-Americans worked in blue-collar occupations, and were active in trade unions, American labor organizations became important conduits for Irish-American support for the fight back home. It’s estimated that between 1850 and 1900 Irish workers sent $260 million back to Ireland to support their families, as well as anti-British activists. Organizations such as the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the Knights of Labor, and Clan na Gael funneled money to rebels and, from the 1880s on, smuggled guns to equip their fledgling armies. Many of the weapons used by Connolly’s Citizen Army (the armed wing of the Irish labor movement formed during the Dublin transit strike of 1913 by Connolly, James Larkin, and Jack White) had been paid for and kitted out by Irish-Americans.

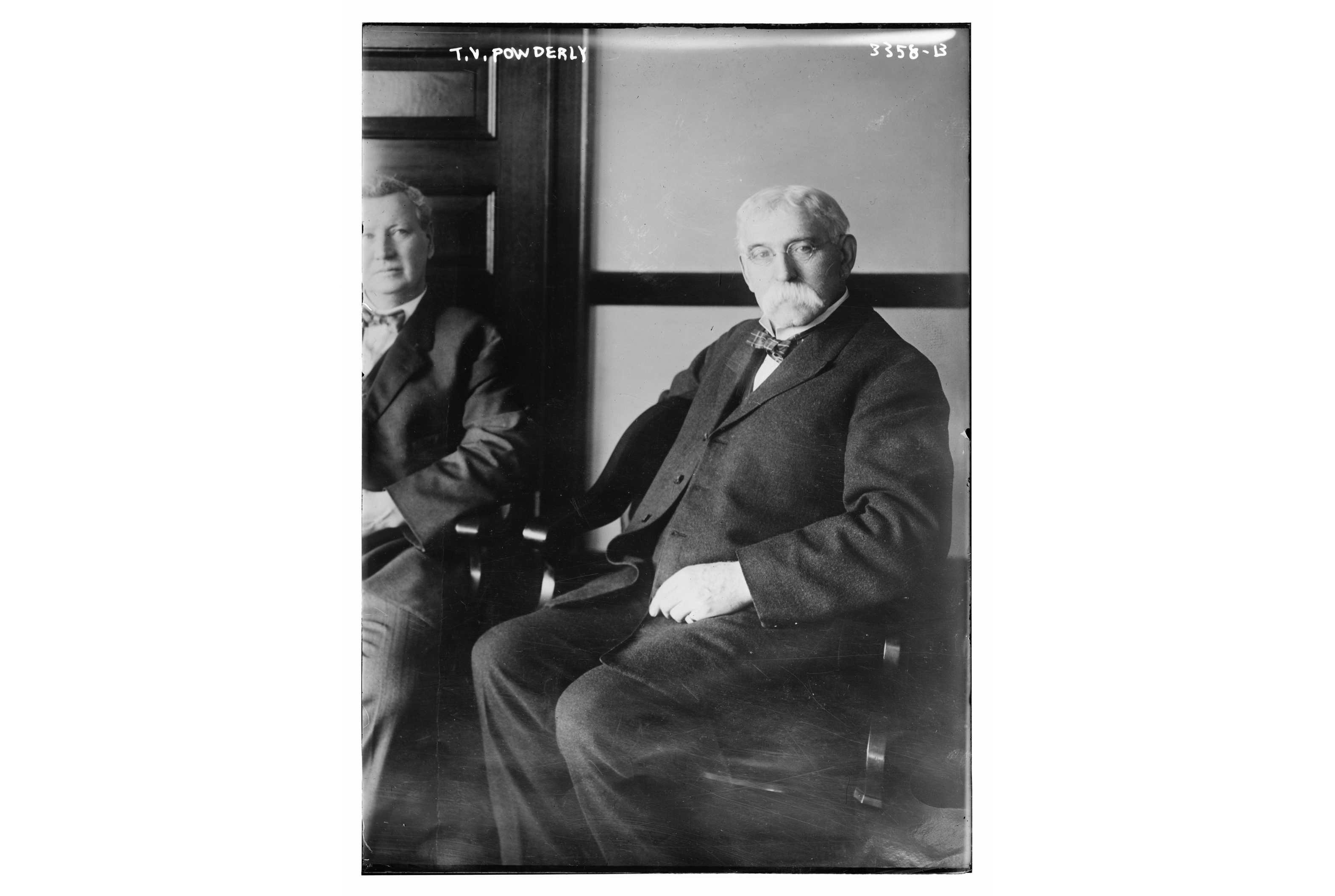

Throughout the 1880s, as the issue of land reform heated up in Ireland, Irish-American labor leader Terence Powderly and his Knights of Labor raised money from Irish workers in the U.S. to support the oppressed peasants in Ireland. Powderly also brought Irish leaders, land reformers, and Home Rule politicians, including Charles Stuart Parnell, Michael Davitt, and John Dillon, to the U.S. to promote the cause of Irish independence. A critically important figure in the history of the American trade union movement, Powderly transformed the small, secretive Knights of Labor into one of the largest, most visible, and most powerful labor organizations in late 19th century America.

When Irish Republican leader John Devoy was exiled to the U.S. in the 1870s, following his role in the rebellion of 1867, he joined the recently established Irish Republican organization, Clan na Gael, and was soon elected Chairman of its Executive Board. Under his leadership, Clan na Gael became one of the leading Irish republican organizations in the U.S., and one of the premier organizations raising money for activists in Ireland. Devoy allied Clan na Gael with the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and began sending funds raised by Irish American workers to its membership in Ireland. Clan na Gael member, and multi-term President of the group, John Kenny, also exiled from Ireland, used the cover of business and personal trips to smuggle funds, intelligence, and supplies to the I.R.B. By 1916, Clan na Gael was the largest single source of funds for both the Easter Rising and the Irish War of Independence. As events unfolded on Easter Sunday 1916 in Dublin, it was Devoy who read the Declaration of the Irish Republic to a large gathering of Irish workers in New York City. Devoy would later declare that, “without financial contributions from U.S. labor unions, there would have been no uprising in Ireland.”

The influence of long practiced political activism traveled west across the Atlantic, too, as Irish immigrants responded to the challenges they faced in their new home. Our immigrant ancestors had hoped to find a refuge from famine, religious persecution, bigotry, and discrimination in America. But, when they arrived here, they discovered there was a gap between promise and reality, and they encountered discrimination and mistreatment similar to what they had suffered at the hands of land agents, absentee landlords, and British occupiers back home. So, just as they had banded together to form the Land League in Ireland, they banded together in America to form some of the country’s very first labor organizations. Labor leaders, such as Terence Powderly, the son of Irish immigrants, and Mary Harris, “Mother,” Jones, who had immigrated to the U.S. as a child, brought to America’s mines, factories, and construction sites the same passion for justice and the same combative spirit that characterized the struggle for a free and united Ireland. Irish immigrants were among the founders and early leaders of my own union, the Laborers’ International Union of North America (LiUNA), then known as the International Hod Carriers’ and Building Laborers’ Union.

From the moment the first wave of Irish immigrants arrived on American shores, they began standing up for each other, and by doing so, built the foundations of the local trade union movement. And just as their brothers, sisters, mothers, and fathers had fought to break the chains of British domination in Ireland, so Irish American labor leaders fought to break the chains of virtual slavery here in the States.

These Irish American working class warriors also brought with them many of the tactics they had used successfully to fight British rule in Ireland. They formed secret societies, such as the Molly Maguires, the activist Irish coalminers in Pennsylvania, to wage an underground war against exploitive and abusive owners and employers. To put pressure on business they used boycotts – a tactic that was first employed in Ireland against the despised British land agent, Charles Boycott, and from whom it takes its name. It was also an enduring belief in the power of solidarity that Powderly and other Irish-American union leaders brought with them from home, most likely influenced their decision to organize workers across craft lines, without regard to race or ethnicity.

One hundred years later, the connections between Ireland and Irish Americans in the labor movement are stronger than ever, and have never been more important as the peace process continues to evolve. American and Irish union leaders face many of the same challenges: attacks on collective bargaining; austerity policies that decimate working families and hinder economic growth; continued assaults on trade unions and working people. Even as an ocean divides us, we are bound together by common values that are as old as Ireland’s struggle for freedom and independence: dignity, justice, equality, and self-determination.

In the coming years, let’s continue to be inspired by the lives and legacies of Jim Larkin, James Connolly, Constance Markievicz, Terence Powderly, Mother Jones, John Devoy, and the many other brave men and women who fought, sacrificed, and laid down their lives in the cause of labor and the cause of Ireland. And let’s pledge to one another, in Ireland, in the U.S., and around the world, that we will never back down, never back up, and never, ever, surrender in the ongoing fight for workers’ rights, civil rights, and human rights. ♦

Terry O’Sullivan was inducted into the Irish America Hall of Fame in 2017, read Terry’s profile and watch his acceptance speech.

_______________

Terry O’Sullivan is general president of the Laborers’ International Union of North America. This article was published in the February / March 2016 edition of Irish America.

Return to Labor Day 2020 to read more.

Hi, thanks a lot for this. I was surprised not to see a mention of a number of Irish-UStater trade union organisers whom I had thought quite famous. One was called Quinn or Quill, I seem to recall, organised black and white public transport workers at a time when that was unusual to do.

Was I mistaken?

You are absolutely right. Mike Quill was the greatest of Irish American labor leaders. And a member of the IRA in the War of Independence.