Éamon de Valera, the dominant political figure of Ireland’s 20th century, was an enigmatic figure to the end of his life.

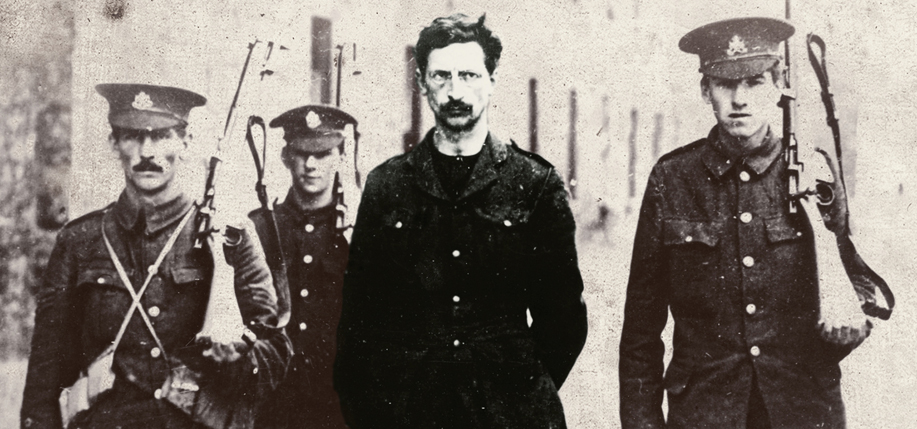

Éamon de Valera was sentenced to death for his involvement in the 1916 Easter Rising, but, under circumstances that are still a mystery, he escaped the firing squad and was instead shipped off to prison in England.

Later that year, in July, the United States Embassy in London, prompted by requests from de Valera’s relatives in America, contacted the British Home Office for a report on the prisoner’s status and for a statement from him about his citizenship.

Six weeks later, the Governor of Dartmoor Prison passed on the following information from the 33-year-old de Valera: “The prisoner gives New York as his place of birth. He states that he has asked his mother to find out whether his father – who was a Spaniard – became an American citizen. If so, he (the prisoner) claims to be such. If not, he is a Spaniard. He further states that he did not become a British citizen, but he would have become an Irish citizen if that had been possible.”

So then, vehemently not a Brit, and, if he couldn’t be an Irishman, happy to be an American or a Spaniard, de Valera enters public life as something of a mystery man. And, while his political career spanned half a century, and he served as President of the Irish Republic for two terms, from 1959 until 1973, questions about his origins and character continue to be debated today.

Complexities of citizenship aside, a person’s name doesn’t usually demand explanation. But that’s not the case with de Valera.

Born on October 14, 1882, his original birth certificate gave his name as “George de Valero.” A corrected birth certificate for “Edward de Valera” was issued by the State of New York in 1910. In addition to the birth certificates, two baptismal records exist – one for “Edward De Valeros,” and an amended one for “Eamon de Valera.”

De Valera lived in the U.S. for only two years before his mother, Catherine Coll, had her brother Edward take him to Bruree, Co. Limerick, to be raised by members of her family. At the local school, he was enrolled as “Edward Coll,” rather than “Edward de Valera.” And later, “Edward” morphed into “Éamonn,” a result of his participation in the Gaelic League. Then, for several years, “Éamonn” spelled his name with two n’s – but dropped one of them as he became more involved in public life.

During the almost six decades de Valera spent in the hurly-burly of politics, he consciously shaped his identity, which seems to have added to the sense of mystery about him. Making a new name for himself – Éamon – seems to have been the start of that process, one that would continue for years, as he became who he wanted to be seen to be.

De Valera’s first full-time employment was as a mathematics teacher, and he served at several colleges in Ireland. In November of 1913, he joined the Irish Volunteers and later, as the prospect of an insurrection loomed, the secretive, oath-bound Irish Republican Brotherhood.

Interestingly, de Valera harbored serious misgivings about the planning for the Easter Rising, and did not believe he would survive the impending skirmishes with the British Army. In his authorized biography, Éamon de Valera, the Earl of Longford and Thomas P. O’Neill write that, “he felt that death was almost inevitable.”

He survived Easter Week’s fighting, but, following his surrender, he was immediately staring death in the face again, this time by firing squad in Kilmainham Goal. He wrote letters of farewell to his family and friends, so he must have been surprised when he was reprieved, and sent to jail instead.

He was released in 1917, as part of a General Amnesty for Irish political prisoners, and immediately embarked on a career in electoral politics. He became president of Sinn Féin, a post he held until 1926, and he represented Clare in a parliamentary seat until 1959.

In early 1919, Sinn Féin members of the House of Commons formed a revolutionary Irish parliament, known as Dáil Éireann. And in April that year, following another stint in an English prison – and a movie-worthy escape from it – de Valera was elected Priomh Aire (Chief Minister) of the Dáil.

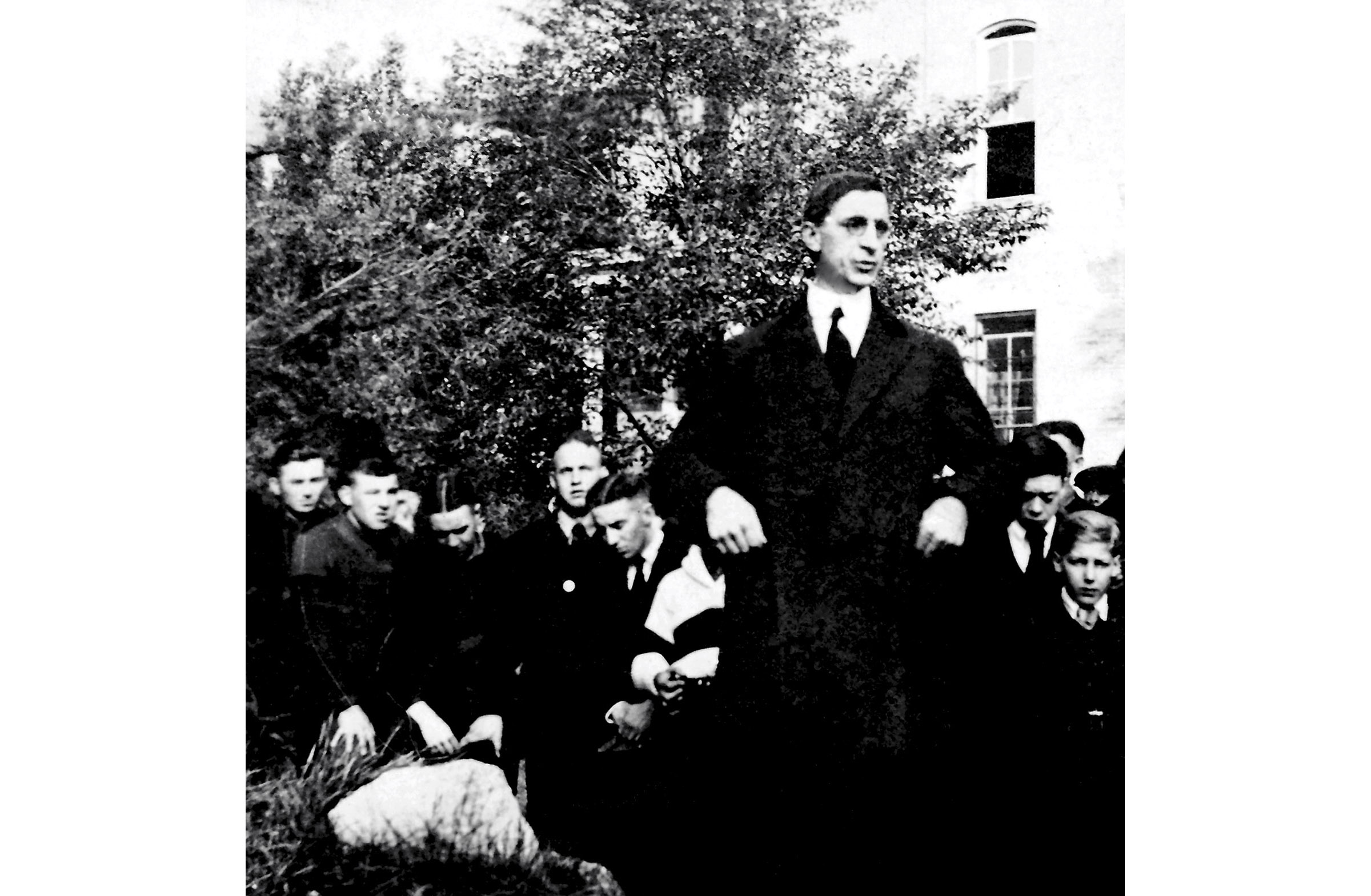

The exciting personal dramas that are part and parcel of de Valera’s life – dodging a firing squad bullet, his daring jailbreak – continued when he stowed away on a ship bound for the U.S., and arrived in New York on June 11, 1919. This was his first trip back to the land of his birth since he was a toddler. His visit lasted 18 months and, during that time, he solidified his reputation in the minds of Irish Americans as being the native son of U.S. soil that would emerge as a major figure in Ireland’s future.

De Valera’s purpose in coming to New York and travelling throughout the U.S. was to promote and get support and recognition for the idea of an Irish republic. He set the message for the visit during his first press conference at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York, when he was introduced as the “President of the Republic of Ireland.”

In his book, With De Valera in America, Patrick McCartan, a Dáil member and Sinn Féin’s representative to the U.S., explained how the title “President of the Republic of Ireland” came about, since in reality, no republic existed. “De Valera pointed out that he was not President of the Republic of Ireland, but only Chairman of the Dáil,” McCartan writes.

But the spin doctors advising de Valera weren’t all that worried about falling foul of the niceties of constitutional law when projecting the best image for him. Since George Washington’s time, Americans had a clear understanding of the role of a president in a republic – he was the democratically elected leader of the state – and that is what de Valera became.

During his time in the U.S., “the president” spoke to massive crowds, raised millions of dollars, and made enemies with two key figures in the Irish-American republican movement – John Devoy and Daniel Cohalan.

While in the U.S., de Valera founded the American Association for Recognition of the Irish Republic as a vehicle to funnel financial support from Americans through his hands. This move angered Devoy, who had long been recognized as the voice of the Irish revolution in America. He used his weekly newspaper, The Gaelic American, to denounce de Valera for his guile, and later nursed a lifelong loathing of him.

Because of de Valera’s imprisonment and sojourn in the U.S., he was away from Ireland for most of the Irish War of Independence, which ended with a truce on July 11, 1921.

The following month, in the Dáil, de Valera pushed for a change to the 1919 Constitution to upgrade his office from prime minister, or chairman of the cabinet, to full president of the Republic. Ironically, two years after his American supporters had bestowed an invented presidential title on him, de Valera now assumed it, even though Ireland wasn’t a republic – and wouldn’t be until 1949. Even so, by making himself head of state he was able to argue that, since the British head of state would not attend the peace conference that led to the Treaty and the partition of Ireland he would not attend either. His maneuverings meant that, when the Treaty proved contentious, he was able to avoid any blame for it, because he had not been at the negotiating table.

When the Treaty was ratified on January 7, 1922, de Valera resigned as president and led a large minority of anti-treaty Sinn Féin T.D.s from the Dáil. By June, the pro- and anti-treaty sides were locked in a civil war that lasted until the following May.

For the first several years of the 26-county Irish Free State, the entity that had been established by the Treaty, de Valera was at odds with his former colleagues in government and struggled politically. But then, in 1926, he was instrumental in founding Fianna Fáil and, when it became the largest party in the Dáil, following the general election of 1932, he was appointed President of the Executive Council.

In that role, essentially prime minister of parliament – the title was changed to “Taoiseach” in late 1937 – de Valera was head of the Irish government from March 9, 1932, until February 18, 1948. Later, in the 1950s, he served two more times as Taoiseach, prior to being elected head of state, as President of Ireland, in 1959.

Taken together, he was either head of government, or head of state, for a remarkable 35 years between 1932 and 1973, and to call this period “The Age of de Valera” is no understatement.

During his time at center stage, de Valera always kept an eye on the republic of his birth. He went on speaking and fundraising tours in the U.S. during the late 1920s to build support for his new Fianna Fáil party and himself.

During his visits, the issue as to whether his American citizenship had helped him escape a firing squad in 1916 became a recurrent story in the press, and the meme that an Irish rebel commandant was saved from British Army injustice because they had to bow to his U.S. heritage, was a popular one in Irish America, and even more broadly.

It’s a story that continued to engage. When John Kennedy, U.S. President, visited Ireland in 1963, he talked to de Valera about it the last night the American presidential party was in Dublin. In their book Johnny, We Hardly Knew Ye, Kennedy aides Kenneth P. O’Donnell and David F. Powers report that he asked his Irish host why he had not been shot in 1916.

“De Valera explained that he had lived in Ireland since his early childhood,” they write, “but he was born in New York City, and because of his American citizenship, the British were reluctant to kill him.”

Six years later, however, de Valera had changed his mind, if not the facts. He wrote: “The fact that I was born in America would not have saved me.” He added: “I have not the slightest doubt that my reprieve in 1916 was due to the fact that my court martial and sentence came late.”

Was the president of Ireland, then 86, privy to new information? Or was he continuing the process of shaping a preferred identity, this time one that would be seen not as half-Spaniard or half-American, but as completely Irish.

While de Valera did, in the end, become a world statesman and a quintessentially Irish leader who steered the nation he had helped create for most of his life, when biographers, historians, and journalists study his legacy, the footnote to an amazing life that never fails to engage them is, whether his seemingly miraculous escape in 1916, was due to an accident of birth, the slow grinding of his court martial, or simply pure blind luck.

Since the man himself gave two different reasons, at two different times, to account for his salvation, there’s every likelihood it will still be an engaging footnote another hundred years from now, and de Valera, man of mystery, will still be an enigma. ♦

Read about Kennedy’s visit to Ireland and Read De Valera’s memories of the visit in The American Cousin: Memories of JFK’s Trip to Ireland.

Robert Schmuhl is the inaugural Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Chair of American Studies and Journalism at the University of Notre Dame, where he is also director of the John W. Gallivan Program in Journalism, Ethics & Democracy. The author or editor of a dozen books, his most recent is Ireland’s Exiled Children: America and the Easter Rising, published by Oxford University Press. His article in this issue is adapted from the chapter about Éamon de Valera in that book.

I am interested in de Valera’s US speaking tour, particular those places closest to the Canadian border, to which sympathetic Irish-Canadians would travel to hear him.

I don’t know about the entire tour. ,mid 1919 to end 1920.That would be a great contribution to Irish-American history. I have researched deeply and have documented how Guy Golterman and the Nation’s Forum reached out to the voice, added 3 De Valera recordings to the most important series of recordings in U.S. History, and vigorously marketed them to help raise money for the Cause. I would think a tenured professor at one of the Universities would assign out development of the full speaking tour itinerary, as it began 100 years ago this June or July.

We are listening to DeValera’s Nation’s Forum recordings at the March meeting of the Kentucky Antique Phonograph Society next month. Has your research been published where I might access it by way of introduction before we listen to the recordings? I think they are an incredible historical artifact and consider myself quite lucky to own a set.

Hello,

My name is Luke Fater, I’m an editorial fellow at Gastro Obscura. We’re a travel website exploring the wonders of our world through the lens of food and drink.

I’m working on a story about de Valera’s 1919 prison escape (via fruitcake) and I’d like your permission to use the first photo from this webpage. It’s really well done and suits my story quite well.

Please let me know as soon as possible.

Thank you,

Luke Fater

luke.fater@atlasobscura.com

While Eamon De Valera’s first election appears to be County Clare. But wasn’t his first election in County Down,

Northern Ireland. Correct me if I’m wrong. I believe his election for Clare came later.

No Mention of his death sentence reprieve from the free State . When he was captured , And the ending of civil war hostilities.. Or was the just remarkable luck too ?.

I grew up during the De Valera era. He was a disaster and ensured the theocracy of the Roman Catholic Church with its hold over the Irish State. He was a disaster for free thinking people.Thankfully this period has past as his woeful legacy becomes buried in time.

Yours etc.

Leslie Blennerhasset, M. A.