Sean Reidy visits the O’Neill family home in New London, Connecticut, and on his return to Ireland, visits the O’Neill homestead in County Kilkenny.

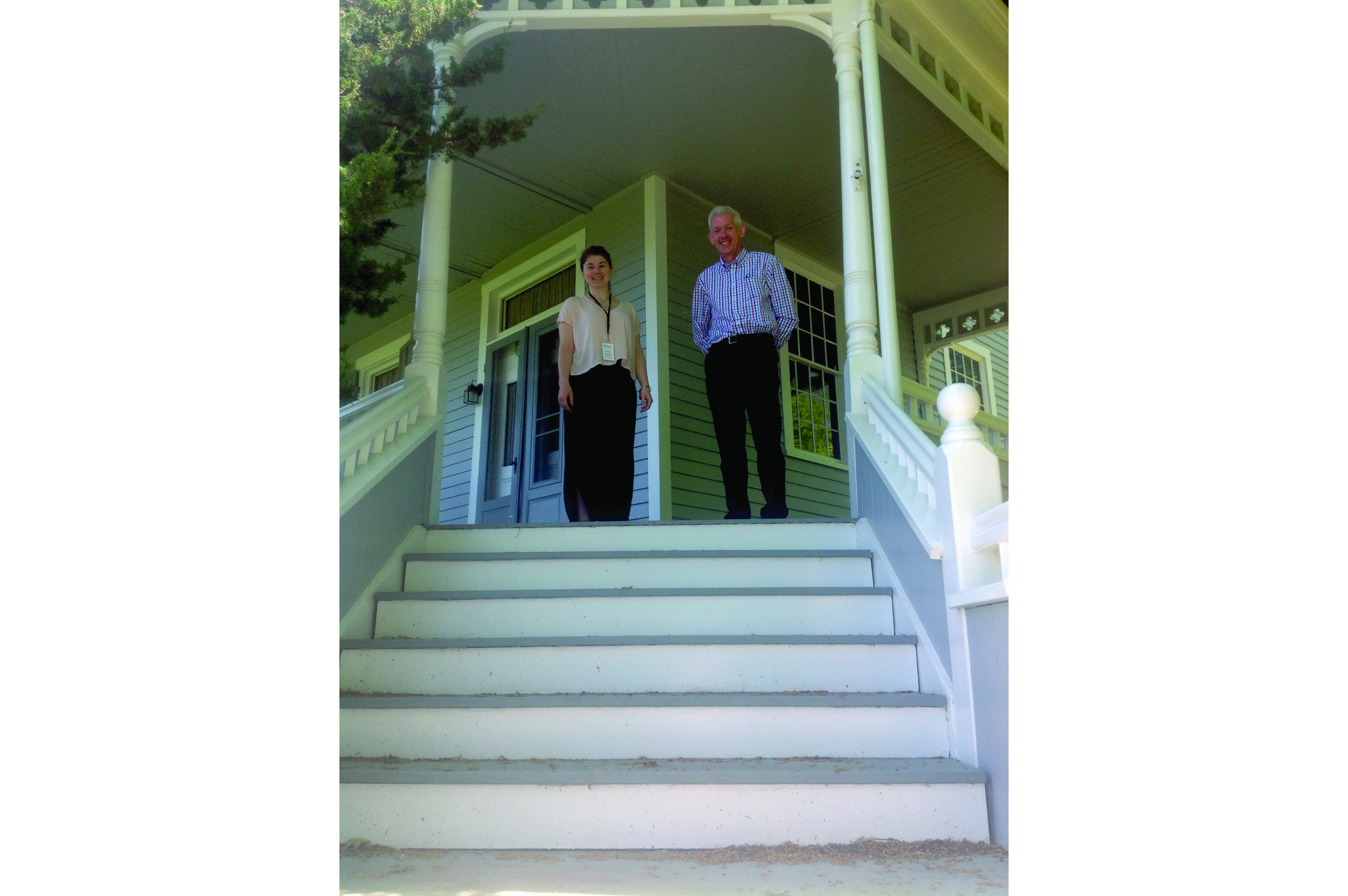

In May 2015, I visited the Monte Cristo Cottage in New London, Connecticut, the childhood home of celebrated playwright Eugene O’Neill. I made the journey with Richard Hayes, Head of Humanities at Waterford Institute of Technology, an O’Neill scholar.

For both of us, it was a pilgrimage to a sacred site, but for different reasons. Richard, having read all of O’Neill’s works, is moved by O’Neill’s genius. For me it’s the story of Eugene’s father, James O’Neill, that fascinates.

James O’Neill had a remarkable life, emigrating from Ireland at the age of five, abandoned by his father at 10, raised by a mother who spoke very little English. Yet, having little formal education, he was playing Shakespearean roles by his early twenties, and his son Eugene went on to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

It was a memorable visit. We had a wonderful guide in Mary Reagan who brought alive the story of the Monte Cristo Cottage. As we sat in the living room, where Eugene O’Neill’s autobiographical Long Day’s Journey into Night takes place, Mary delivered the final speech of the play when Mary Tyrone, the character based on Eugene’s mother, recalls falling in love with James:

“Then in the spring something happened to me. Yes, I remember. I fell in love with James Tyrone and was so happy for a time.”

The play reveals the Tyrone family at odds with the world and at odds with themselves. The mother, Mary, introduced to morphine during a difficult birth and now addicted to it, is torn between her love for her husband and sons and her desire to lose herself in morphine and vanish from their sight. One son, Jamie, is a disillusioned actor and alcoholic; the other, Edmond (Eugene), is the sickly, dark, brooding, intellectual younger brother. (In real life, there was a third son, Edmund, who died young). The father, James, is a highly successful actor but embittered by being trapped in a role that does not fulfill his potential, and also embittered by being abandoned by his father at 10 years of age.

Long Day’s Journey into Night resembles the life of the O’Neills in many respects, including Mary “Ella” O’Neill’s addiction to morphine, and James O’Neill’s squandering of his potential as an actor for the cash that one role brought in. (The playwright described it as “a play of old sorrow, written in tears and blood.”) But for now, let’s skip over the obvious parallels between the play and the O’Neills’ home life, and go back to the beginning for a better understanding of James’s fear of the poorhouse.

The story begins in the townland of Tinneranny, in the parish of Rosbercon in County Kilkenny in the mid 1800s. Edmund O’Neill and Mary O’Neill, two distant cousins, marry. They have a small allocation of no more than 10 acres. When James, their sixth child, is born on October 14, 1845, he is delivered into a world of turmoil. The month before, in September, a strange disease struck the potatoes, turning them black and rotten. The blight had struck with dire consequences.

The next five years were a nightmare for the O’Neills. Prior to the blight, they had just enough money to survive on, but as most of what they produced went to the landlord for rent, they had little to sustain themselves. The future prospects for the children (a seventh child, Anastasia, was born in 1848) are very bleak and they decide, like many others at the time, to seek passage for a better life in America.

William Graves and Son, a merchant family, are offering regular sailings to Quebec out of nearby New Ross, less than three miles away, and the O’Neills set sail on The India, a three-masted barque, on April 5, 1851.

It’s an arduous journey with only two bunks six feet by six feet allocated to the entire family. But at least the Graves ships were well run and passengers usually arrived in good condition. The O’Neills landed, after 38 days at sea, in Quebec on May 11. After clearing quarantine in Grosse Isle on the St. Lawrence River, the family went by steamer to Buffalo, where most likely they were met by friends or relatives who helped them find accommodation. Buffalo had a large Irish community at the time, but the situation that the O’Neills found themselves in was probably less than ideal. In 1851, the Buffalo Courier described the heavily Irish First and Eighth Wards as “the spectacle of a most squalid poverty hardly credible in this land of plenty.” This is where five-year-old James began his life in America.

There is very little account of what happened to the family in Buffalo, but we do know that about five years later they moved to Cincinnati, Ohio. At around this time Edmund returned to Ireland, where he died soon afterwards.

In the play, Mary credits Edmund’s desertion as the reason for her husband’s “close-fisted” approach and tries to justify his behavior to her son:

“Your father is a strange man, Edmund. It took many years before I understood him. You must try to understand and forgive him, too, and not feel contempt because he’s close-fisted. His father deserted his mother and their six children a year or so after they came to America. He told them he had a premonition he would die soon, and he was homesick for Ireland, and wanted to go back there to die. So he went and he did die. He must have been a peculiar man, too.”

If the real-life Edmund did have a premonition of his death, or if he planned to return to America, or bring his family home to Ireland, is not known. On June 18, 1862, he died of poisoning. An enquiry into his death was inconclusive.

And here we see how the incident is played out in Long Day’s Journey when James Tyrone tells the story himself:

“When I was ten my father deserted my mother and went back to Ireland to die. Which he did soon enough, and deserved to, and I hope he’s roasting in hell. He mistook rat poison for flour, or sugar, or something. There was gossip it wasn’t a mistake but that’s a lie.”

Patricia O’Neill, a relative of Edmond’s wife, Mary, who lives in Tinneranny, County Kilkenny, is adamant that research compiled with great diligence over many years by her late father Brian shows that Edmund was poisoned by an in-law over land he had laid claim to.

Patricia brought me to see what remains of the original O’Neill homestead – a broken-down wall – and to the cemetery in Ballyneal where Edmund O’Neill is buried. (Ballyneal translated into Irish means the townland of the O’Neills. This area is still an O’Neill stronghold.)

Patricia confirms that her cousin Mary, Edmund’s wife, was a native Irish speaker whose lack of English would have made it difficult for her to earn a living. And we know that when James was in his early teens the burden fell on him to become the breadwinner.

His two older brothers left home (one was killed fighting in the Civil War), and James left school to find work. Through John and William O’Neill (who may have been cousins) he got an apprenticeship in a machinery shop. Later, his sister Anastasia’s husband helped him find a job making uniforms for the military and later costumes for the stage, and also arranged for a tutor to help with his education.

James’s work often found him backstage at a theater company in Cincinnati. When an opportunity arose during a strike by actors he was able to step in and read a part in The Colleen Bawn, a melodramatic play by Irishman Dion Boucicault. This first stage appearance would set off his meteoric rise in the theater. In no time he was playing a variety of roles, including Romeo in Romeo and Juliet opposite Adelaide Neilson, the English-born actress who described him as “the greatest Romeo I ever played with.”

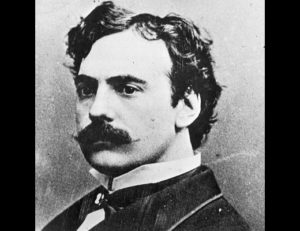

In addition to classical good looks, James had a magnetic stage presence. The San Francisco Chronicle of August 3, 1879 described him as “…a quiet gentleman of medium height, well-proportioned figure, square shoulders and stands very erect. He has black hair, black eyes, rather dark complexion, a black mustache, and a fine set of teeth which he knows how to display to advantage.”

James was quite the matinee idol and particularly popular with women. However, when Ella Quinlan’s father, a friend of O’Neill’s, took her to see him in A Tale of Two Cities, the actor and the convent schoolgirl fell in love and two years later, on June 14, 1877, at St. Ann’s Church on 12th Street in New York City, they were married.

Their son James Jr. was born the following year, in San Francisco. And another son, Edmund, was born in 1883. That year James took over the lead role in the Count of Monte Cristo at Booth’s Theater in New York, after Charles R. Towne died suddenly in the wings after his first performance.

He was a sensation, and soon bought the rights to the play and set up his own company to tour. Ella joined him on the road, leaving behind James Jr. and the young baby Edmund in New York. While they were away, Edmund contracted measles and died, and it is said that Ella never forgave herself.

In 1888, Eugene was born in a hotel on Broadway and 43rd Street. By this time James was on the road with his traveling company, he toured with Monte Cristo for nearly 40 years. Except for the Monte Cristo summer cottage the family never had a home.

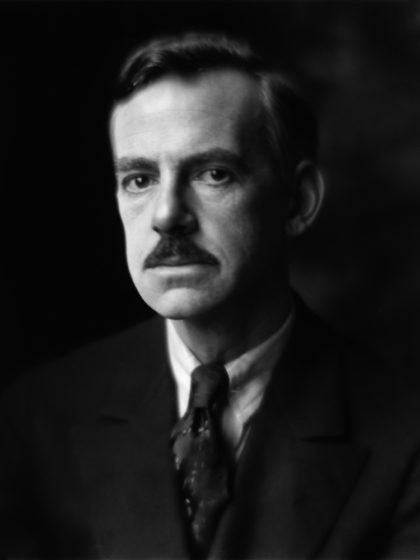

According to Eugene: “My father was really a remarkable actor, but the enormous success of Monte Cristo kept him from doing other things. He could go out year after year and clear fifty thousand in a season. He thought that he simply couldn’t afford to do anything else. But in his later years he was full of bitter regrets. He felt Monte Cristo had ruined his career as an artist.”

In August 1920, James was in an automobile accident in New York and while injured in the hospital he was diagnosed with intestinal cancer. He died some months later at the cottage in New London. He was 72. Ella, who had been cured of her morphine addiction in 1914, sold the cottage soon after her husband’s death. On a trip to California with her son Jamie in 1922, she was diagnosed with a brain tumor and died. She was 64.

His parents’ Irish background (Ella was first-generation with parents from Tipperary) became part of Eugene O’Neill’s dramatic heritage. “One thing that explains more than anything about me is the fact that I’m Irish, and strangely enough it is something that all writers who have attempted to explain me and my work have overlooked,” he is reported to have told his son Eugene, in 1946.

Though he never visited Ireland, we need look no further than the Irishman Driscoll in Bound for East Cardiff, one of Eugene O’Neill’s four short plays set on the S.S. Glencairn, to see the author reflecting back to New Ross, County Wexford, the town his father emigrated from in 1851. Driscoll sings the Irish ballad “The Boys of Wexford.” “We are the boys of Wexford who fought with heart and hand….” Coincidentally, the song was also a favorite of President John F. Kennedy, whose family’s homestead in Dunganstown is only five miles from the O’Neill home. I can’t help thinking that if Eugene, like J.F.K., had visited his father’s home place, he too would have got a warm welcome, and perhaps would have found an emotional home for his troubled spirit.

_______________

Sean Reidy was most recently CEO of the JFK Trust, a role in which he was instrumental in developing the Dunbrody Famine Ship Project, the Emigration History Centre in New Ross, County Wexford, and the Irish America Hall of Fame. Sean also coordinated the visit of the Kennedy family to Ireland for the JFK50 celebrations and played a key role in the development of the new Kennedy Homestead Visitor Centre in Dunganstown, New Ross.

This article was originally published in the October / November 2015 issue of Irish America.

Cousin

Where is the remains of the O’Neill homestead in county Kilkenny Ireland?

He was from Tullogher in county Kilkenny! Not New Ross, the ship sailed from New Ross and thats where his connection to Ross ends. Edmund his grandfather is buried in Ballyneale, Tullogher, county Kilkenny. I am a distant relation to the o Neills, my granmother was an o Neill from Ballyneale, which translates in Irish to land of the o Neill’s

The article states quite clearly that James and family were from Tinneranny , Co Kilkenny. Which is Rosbercon , Co Kilkenny..

I don’t understand the rather terse comment about New Ross…his Kilkenny roots are mentioned many times.

Tullogher/ Rosbercon are the same parish Google Tullogher Rosberon gaa club, its a bit confusing! I know where the remains of their homested is and it is no where near Rosbercon, check google map and you will see its beside Ballyneale in Tullogher

Great granddaughter

I will be in Kilkenny this December and would love to visit the graveyard. My theatre company will be producing Long Day’s Journey next year and this would be a rich experience. Can you tell me how to find it?

I am doing research for a past life connection. I had Googled my name a few months ago and the photographs I found of James O’Neill look similar to me. Are there any articles written that describe his mannerisms or personality traits? Do you happen to have anything with his handwriting?

Thank you, James O’Neil