America entered World War One on April 6th, 1917, and many Irish and Irish-Americans saw it as their duty to enlist. Megan Smolenyak looks at the great state of New Jersey and profiles several of those soldiers, including her grandfather, who heard the call of duty.

He was Pop-Pop to me, and I remembered him as the gentle, older fellow who would give me a penny for gum when we went on a stroll to the neighborhood drug store. Other times, he would sit on the bottom step leading up to the bedrooms in his Chatham, New Jersey split level – the driver accepting my pretend fare as I climbed the stairs behind him to take a seat in our imaginary city bus.

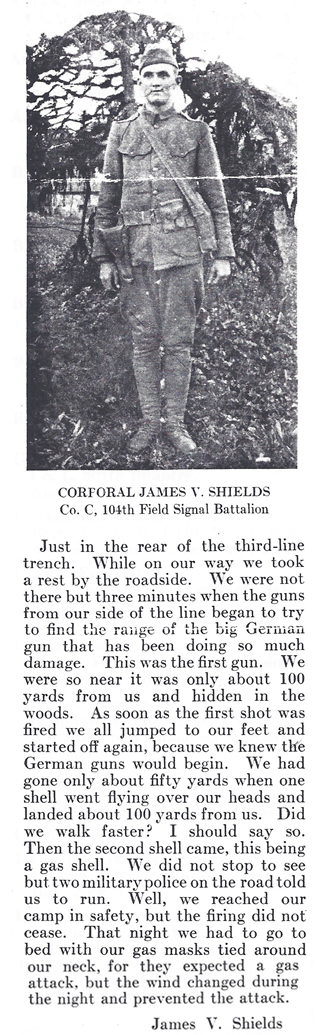

But we lost him when I was only four, so the life of James Vincent Shields remained a mystery to me until I became a genealogist in the sixth grade and started pestering my nana for memories of the past. And even then, it would take some time to learn that he had served in World War I. Born in Jersey City in 1898 to Irish immigrants David and Margaret (McKaig) Shields, James was the ninth of eleven children. In 1923, he married Beatrice Agnes Reynolds after she accepted his proposal with a specially made ring engraved with shamrocks.

They had three daughters – Peg, Bea, and Seton – stretched across a 15-year period, and Pop-Pop supported the family by commuting into New York to work for assorted banks on Wall Street.

Before embarking on family life, though, James was a soldier in World War I. He answered the call of duty in April 1917, three weeks after President Wilson received the declaration of war he had requested from Congress. Most of his military records were destroyed in a 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center, but we know that he was assigned to the Signal Corps and shipped overseas on June 19, 1918, remaining in France until May of 1919.

Compared to many, he came through relatively unscathed. I recall whispers of his having been gassed and jokes about a minor leg injury from tripping over barbed wire, but like so many men of his time he kept his war stories to himself. Perhaps the only flash of insight we have is from a newsletter that Irving Bank, his employer at the time, published with letters from servicemen who worked for them.

In his usual understated way, James wrote:

[W]e knew the German guns would begin. We had gone only about fifty yards when one shell went flying over our heads and landed about 100 yards from us. Did we walk faster? I should say so.

My family was lucky. James V. Shields came back alive. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be here to write these words, and it was in seeking to learn more about my grandfather’s military service that I discovered a database offered by the New Jersey State Archives: World War I Deaths: Descriptive Cards and Photographs.¹ I combed through individual profiles of some of the 3,427 men from New Jersey who sacrificed their lives in WWI, and decided that their stories need to be heard. To that end, I selected and researched several of them and would like to share at least a snippet of their lives to help ensure that these Jersey boys, like my grandfather, are not forgotten. As a modest tribute to him, I have chosen from among the 69 Irish immigrants in this collection.

℘℘℘

Joseph J. Cassidy came from a close family. Born to Patrick and Margaret (Walders) Cassidy in 1896, he joined older siblings James, Stephen, Thomas, Mary Jane, and Bridget. The 1901 Irish census finds them all ensconced in their home in Rathconnell, Westmeath, where Patrick worked as both a carpenter and farmer.

Maybe times were hard or perhaps the news they received from Margaret’s sister, Annie, in America was too tempting. Whatever the reason, the whole family departed for Princeton, New Jersey in April 1904, shortly after Joseph turned eight.

In Jersey, the men in the family pursued the same occupations they had in County Westmeath, and within a few years, Joseph’s older siblings started marrying and moving out. It seems the Cassidys made a smooth transition to life in America as they already owned their home by the time of the 1910 census.

On June 5, 1917, 21-year-old Joseph dutifully registered for the draft, indicating that he had already spent two years in the National Guard. Less than three weeks later, he enlisted. Private Cassidy spent his first year stateside, but in June of 1918, was sent to France with the 111th Machine Gun Division.

On October 22, 1918, Joseph’s name appeared in the local newspaper back home, but not for reasons pertaining to the more than 24 hours of continuous shell fire he was then enduring with his diminishing gun crew, but because of his sister Mary’s death. Listed as a survivor, he would lose his own life the next day.

His parents were probably still numb, but presumably proud, three months later when they accepted Joseph’s Distinguished Service Cross for “extraordinary heroism in action,” recognizing his valor in directing and encouraging his men in spite of illness, exhaustion, and non-stop shell fire which eventually killed him even as he continued to man his machine gun. They must have gazed at that cross often as it would be another three years until they received their son’s remains.

℘℘℘

Born in 1882, Patrick Farrell was older and more seasoned than most recruits. One of at least seven children of John and Bridget (née Rhatigan) Farrell, he appears with them and a couple of his older siblings in the 1901 census in Lisrevagh in the Rathcline parish of Longford. Showing every indication of intending to remain in Ireland, he didn’t emigrate until May of 1915 by which time he was 33 years old. Perhaps he had lingered to help care for his aging parents.

Slender, but towering over most of his contemporaries at 5’11” (of the 30 travelers on his page of the S.S. New York’s manifest, only one other stands as tall), he made his way to the home of his brother John in Edgewater, New Jersey. Because Patrick never truly settled down, his brother’s address would remain his home of record, but if you were to wander down to the dock and swim directly east across the Hudson River, you’d find yourself in the vicinity of 134th Street in New York City, so it’s little surprise that Patrick seemed to have regarded himself as a New Yorker.

Just four months after arrival, Patrick like so many Irishmen before enlisted in the New York National Guard in the 69th Infantry Regiment (widely known as the “Fighting 69th” and later changed to the 165th Infantry). After two years in New York and on the Mexican border, he re-enlisted and was sent overseas in late October of 1917, much earlier than most members of the American armed forces.

Serving with him were Joyce Kilmer of “I think that I shall never see / A poem lovely as a tree” fame, and Father Francis Duffy. Tragically, Sergeant Kilmer would be killed by a German sniper, but Father Duffy survived the war and became the most decorated chaplain in the history of the U.S. Army.

Despite his previous experience, Patrick was one of the first casualties in the regiment, killed on May 3, 1918. His loss was recorded in Father Duffy’s Story: A Tale of Humor and Heroism, of Life and Death with the Fighting Sixty-Ninth, published in 1919:

In this sector we have had just three battle losses. When Company G was in line, a direct hit of a German shell killed two of our old-timers, Patrick Farrell and Timothy Donnellan . . .

Patrick Farrell is better remembered than most. In addition to including him in his book, Father Duffy wrote a letter of condolence – one which remains in the family today – to his brother, John. This is mentioned in Patrick’s entry in the Longford at War website (www.longfordatwar.ie), where he – unlike most of the 69 Irish in this New Jersey database – is commemorated in the county of his birth.

John’s family has since scattered to New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, California, and Washington, but they and Longford at War will soon have another letter to complement the one by Father Duffy, one from John Farrell about his brother.

℘℘℘

When Alexander Nelis enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1917, he was following in his father’s footsteps, but due to his peculiar family history, it’s quite possible he never knew this. In 1890 when his parents, John and Ann Jane (Diver) Nelis, married in Strabane, County Tyrone, John was with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, a regiment of the British Army.

Within five years, the couple had three children – two daughters and Alexander, named according to custom after his paternal grandfather. Sadly, Alex’s mother passed away in 1897 when he was only three years old, and this marked the beginning of the splintering of his family. One sister died and the other was tucked away in an industrial school. His father remarried to Elizabeth Toman, but soon took off, so the 1901 census finds eight-year-old Alex living with a household of near strangers, the family of his new stepmother.

But life was to get lonelier still. Still married to his father, Alex’s stepmother left for America in 1902, joining relatives in Harrison, New Jersey. Perhaps his remaining sister stepped in to take care of him during his tween years, but by the time of the 1911 census, he was boarding with a Bailie family in County Down where he made his living as a factory worker.

Despite her absence, Alex must have retained a bond with his stepmother as he finally joined her in America when he sailed from Londonderry to New York in June of 1912 and was still living with her at the time of his enlistment five years later. He was employed in Harrison as a grinder for the Hyatt Roller Bearing Company, and apparently intended to stay put as he had taken the first steps in the naturalization process.

Alex served his first year with the Army in the U.S., and was sent to France on June 15, 1918 where he was killed in action on October 25th of the same year. His stepmother, as next of kin, made the decision to have him buried in France. Designated a Gold Star mother, she declined the opportunity to visit his grave overseas, but it can be seen today at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery. Lonely in life, he is at least surrounded by his military comrades in death.

℘℘℘

Born in 1889, Michael Lawlor was the baby of the family, arriving six years after the next youngest. Parents Patrick and Bridget (Shea) Lalor (the spelling morphed) already had five children, but the eldest – their daughter Mary – would be heading to America before long.

The family lived in Monasterevin, a town in County Kildare, situated on the border with Laois. As was all too common at the time, Michael would lose his father when still a youngster, so the 1901 census would find the 11-year-old scholar living in the Oghill district with his widowed mother, sister Bridget, and brother Patt.

His sister Mary was not only living in Manhattan by then, but had already married Daniel Dunn, a brewery worker, in 1899. Michael went to join Mary in 1909, sailing from Queenstown to New York on the Teutonic. Somewhat unusually, he returned home to Ireland for half a year in 1912, but came back to America via Canada that November.

By the time he registered for the draft in 1917, the grey-eyed immigrant had already declared his intention to become an American citizen, but noted that he might be exempt from military service due to his job as a munitions worker in Carneys Point, New Jersey. Nevertheless, he was inducted into the Army on April 5th in 1918 and found himself crossing the Atlantic just three weeks later. On October 18th, he was wounded, and succumbed to bronco-pneumonia days later while still in Europe.

Back in New York, his sister Mary received the dreaded news. After the war when requested to share a photo of her brother, she complied, but like so many in her situation, asked that it be sent back. In all likelihood, it was one of very few images she had of her brother – perhaps the only one.

It’s fortunate for her descendants that she did, though, because the address she included in her letter was key to finding the correct Mary Dunn (a common name), allowing this writer to track down her great-granddaughter, Susan Crimi. Susan had looked into her roots, but had been unable to identify Mary’s siblings, so was delighted when contacted, responding, “I can’t tell you how excited I am to have this new information! And a picture too! Thank you soooooo much!”

“Memory Shine”

Crimi’s discoveries about her ancestors exemplify another layer of the value of this New Jersey collection. In addition to preserving the memories of New Jersey’s heroic doughboys, the details contained and timing involved make these documents a genealogical goldmine for many families, and will often bridge the trans-oceanic gap. Susan had no clue about Michael, but has reclaimed her valiant great-granduncle, and now knows exactly where her Lawlor branch came from in Ireland. And since she’s also learned of Michael’s other siblings, it’s just a matter of time before she locates long-lost kin.

Similarly, Longford at War now has a more complete picture of Patrick Farrell’s life, and Joseph Cassidy has been rediscovered by New Zealand relatives who had previously been stumped as to what had become of this part of the family. Of those included here, only Alexander Nelis remains something of an orphan, but his sister married in 1915, so there’s hope yet.

In his poem “Rouge Bouquet,” Patrick Farrell’s comrade in arms Joyce Kilmer wrote of fallen members of their regiment:

Your souls shall be where the heroes are

And your memory shine like the morning-star.

These Irish Jersey boys gave their lives to a worthy cause, and even a century later, continue to render service by bringing far-flung cousins together. Now it’s the responsibility and privilege of these cousins to make their “memory shine.” ♦

¹ Unless otherwise noted, all photos and other images are from “Department of Defense, Adjutant General’s Office: World War I, Information Cards and Photographs of New Jersey Men Who Died in Service, 1917-1918,” held by the New Jersey State Archives, Dept. of State, in Trenton.

Leave a Reply