On February 7, 1882, John L. Sullivan was on his way to becoming “America’s first sports hero.” All the 24-year-old son of Irish immigrants had to do was throw his hat into the ring. Literally.

Nineteenth-century boxing tradition had it that when a challenger wanted to take on the champ, both would show up at a predetermined fight site and, in a highly elaborate ritual, the challenger’s entour-age would toss a hat into the ring – hence the origin of the phrase still in use today.

That February morning, reigning champion Paddy Ryan – himself born in Ireland – was put on notice: John L. Sullivan was coming after his title.

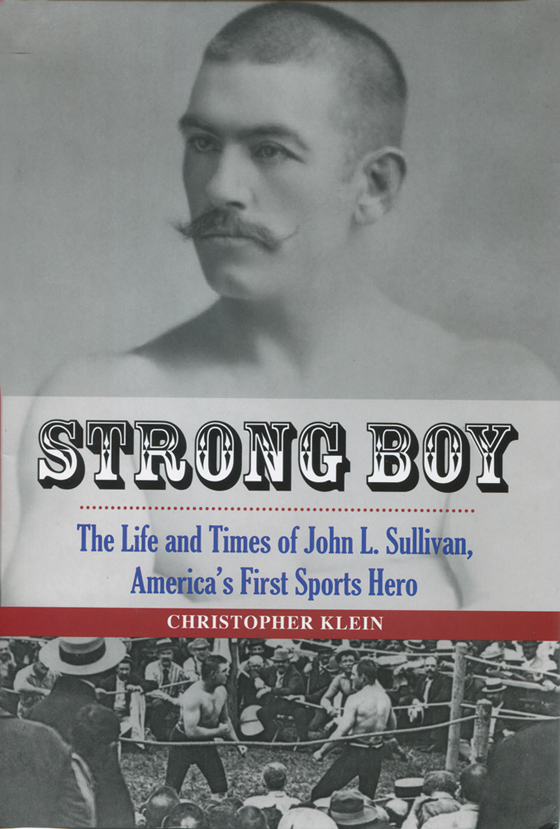

The epic Sullivan-Ryan battle is one of many fascinating episodes included in a new book entitled Strong Boy: The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan, America’s First Sports Hero (Lyons Press) by Christopher Klein.

Sullivan and Ryan had been trash talking for months. Initially, Ryan was able to dismiss Sullivan as a loudmouth upstart. Nevertheless, Sullivan’s “amazing displays of power electrified boxing fans across the country,” Klein writes.

Once Sullivan’s challenge was accepted, there were other matters to settle. In an era when (as Klein puts it) “most American jurisdictions outlawed” boxing, where would this Fighting Irish bout take place? And would it be a match using gloves or bare knuckles? Boxing was undergoing rapid change and Sullivan, for one, saw “gloved fighting as the means to reform boxing and increase its popularity,” Klein writes.

After weeks of debate, however, it was decided that Ryan and Sullivan would battle bare-knuckled style outside of New Orleans.

Prior to the fight, both Irishmen had endured hard journeys.

Sullivan’s father Michael was born in Kerry in 1830, and emigrated to Boston where he met and married Roscommon native Catherine Kelly in 1856. Two years later, a son, John Lawrence, was born.

The precise details of Sullivan’s introduction to the boxing world remain “murky,” according to Klein. What is known is that when Sullivan was around 20 years old, he attended a variety show during which a confident boxer challenged anyone in the audience.

Sullivan promptly knocked the poor fellow “into the orchestra,” and was on his way to becoming the pugilist known as the “Boston Strong Boy.”

Meanwhile, seven years older than Sullivan, Paddy Ryan was born in Tipperary, before moving with his family to upstate New York. Ryan worked on the Erie Canal and as a saloon-keeper before becoming a fighter. Following an 86-round fight against Joe Goss in 1880 (yes, 86!), Ryan claimed the bare-knuckle heavyweight championship.

The stage was then set for the 1882 Ryan-Sullivan fight outside New Orleans, though not before Louisiana Governor Samuel McEnery complicated matters by declaring the fight illegal. This left promoters “less than forty-eight hours to find a new location.”

They settled on a hotel in Mississippi, and while Ryan was ten pounds heavier and had two inches on Sullivan’s reach, “the thirty-seven-year-old champion… couldn’t match the youth of Sullivan.”

When the tenth round came, Ryan’s handlers in his corner “sent the sponge aloft in a sign of surrender.”

Once he was champion, a number of forces converged to make Sullivan not only a champ, but an icon. His cross-country barnstorming tour, during which he challenged literally any and all comers, was covered closely by the increasingly powerful and influential news media. Sullivan’s spellbinding victory over Jake Kilrain in 1889 only added to his legend, first, because the bout lasted 75 rounds, and second, because it was the last bare-knuckle title defense.

Sullivan had ushered boxing into a new era.

Irish Americans, of course, saw Sullivan as a national hero, whose appeal was far wider than the likes of Paddy Ryan or nearly any other athletic star of the late 19th century. Calling him a “minority champion,” legendary sports writer Frank DeFord has compared Sullivan to the likes of Joe Louis, Jackie Robinson and Billie Jean King.

Sullivan finally lost his title to Gentleman Jim Corbett in 1892, and spent his retirement in various pursuits, ranging from actor to business owner. Never exactly careful about his diet or exercise regiment, Sullivan suffered through a series of health ailments before dying at the far-too-young age of 59 in 1918.

By then, however, Sullivan’s legacy was firmly established. He was the last bare-knuckle champion who also laid the groundwork for charismatic, larger-than-life 20th century sports stars such as Babe Ruth. Sullivan was a member of the first class of inductees voted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990. Finally, in a fitting tribute, a barn which Sullivan used to train for the Jake Kilrain fight was converted into the Bare Knuckle Boxing Hall of Fame a few years back, located – fittingly – in Belfast, New York.

Strong Boy: The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan, America’s First Sports Hero By Christopher Klein

(Lyons Press /$26.95/ 352 pages)

Leave a Reply