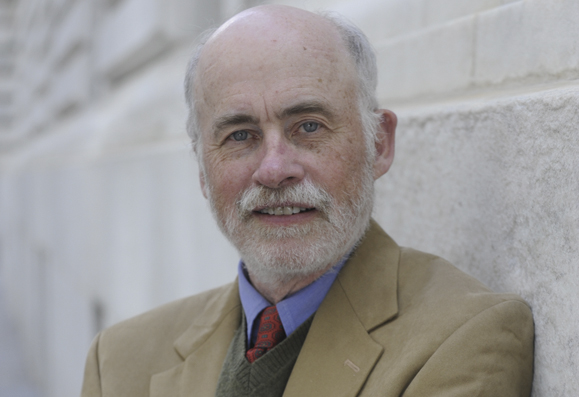

The author Peter Quinn, whose third and final installment of the Detective Fintan Dunne trilogy was released in October, talks to Tom Deignan.

It’s been nearly 20 years since Peter Quinn’s epic Banished Children of Eve, arguably the greatest novel of the New York Irish, was published. Over the course of 600 pages, Quinn depicts the city in all its gore and glory, as the Irish and others struggle to find a place in America, which had absorbed wave after wave of Famine immigrants, only to then be plunged into a bloody Civil War. With extraordinary attention to detail and a diverse cast of characters, Quinn presents the causes and consequences of these seismic events, including the Draft Riots of 1863, and raises important questions about the Irish, immigration, assimilation and the myth of the melting pot.

“Once the Irish stepped off those boats, they were different people. Because now they had to deal with all these other people,” Quinn said recently, seated in the back room of the Old Town bar on East 18th Street in Manhattan.

Now 66, Quinn was alternately comic and reflective, irreverent and earnest, over the course of a wide-ranging interview that covered his writing career, the Irish in America, as well as his latest book, Dry Bones, the third and final installment in his celebrated Fintan Dunne trilogy.

Though set decades after the Civil War, the Dunne trilogy – Hour of the Cat, The Man Who Never Returned, and Dry Bones – all raise similarly dramatic questions about the Irish in America, and the triumphs and tragedies of life in the big city.

As Quinn himself wrote in his 2005 collection of essays Looking for Jimmy, it is important that we remember how “an immigrant group already under punishing cultural and economic pressures, reeling in the wake of the worst catastrophe in Western Europe in the 19th century, and plunged into the fastest industrializing society in the world . . . built its own far-flung network of charitable and educational institutions, preserved its own identity, and had a profound influence on the future of both the country it left and the one it came to.”

Done with Dunne

One of Eve’s millions of banished children was a World War I veteran and ex-cop turned private investigator named Fintan Dunne.

“To me, Dunne is a quintessential Irish New York character – an ex cop, cynical, but not without certain ideals – who thinks everyone is full of shit until proven otherwise. Which is an attitude I’m in love with,” says Quinn, his laughter rising above the crowd noise of the Old Town, a fitting interview location, given its own links to New York’s storied past. Over a century old, with its gleaming mahogany bar, 19th-century bathroom fixtures and Tammany Hall campaign posters, the Old Town is a joint Fintan Dunne himself might have frequented.

“This might be a reflection of my Bronx Irish upbringing,” adds Quinn. “But [the idea] for every one of my novels started with a conversation at a bar.”

In Dry Bones, Dunne is recruited to the Office of Strategic Services – the forerunner to the CIA – by pal and Irish American legend Col. William “Wild Bill” Donovan. It is 1945 and World War II is finally drawing to a close. Dunne and his colleagues must go behind enemy lines to rescue a team of fellow OSS officers. The mission leads Dunne to numerous revelations, the consequences of which reverberate for a decade afterwards. In Dry Bones, we see Dunne not only on the front lines, but also thrust into the prosperous 1950s, where our cantankerous hero has trouble fitting in.

Dry Bones follows The Man Who Never Returned, in which Dunne attempted to solve the notorious real-life case of Judge Joseph Crater, who vanished from West 45th Street in August of 1930, never to be heard from again.

The first entrance in Quinn’s Dunne trilogy was Hour of the Cat, set on the eve of World War II, when Dunne finds himself ensnared in a Nazi scheme involving players on both sides of the Atlantic.

The History-Mystery

Asked if Fintan Dunne is a relative of Jimmy Dunne, the streetwise Irish hustler from Banished Children of Eve, Quinn says: “Fintan Dunne is a relative of Jimmy’s, but I don’t know how . . . the relationship between Jimmy and Fintan is real, but its exact nature is swallowed up in the realities and complexities of famine Irish descendants in New York City.”

All in all, the Fintan Dunne trilogy – aside from being excellent page-turning mysteries – are also brilliant social histories of New York in the middle of the American Century. Best-selling author James Patterson has praised Quinn for “perfecting . . . a genre you could call the history-mystery,” while Pulitzer Prize winner William Kennedy has dubbed the Dunne books “noir fiction at its finest.”

Upon the release of Dry Bones, The Wall Street Journal ran a long review of all three Dunne books, with reviewer Tom Nolan calling Dry Bones “another work of intricate structure, suspense and wit.”

Quinn also believes the books capture something vital about Irish America.

“I like to think that one of the subplots of these three books is the New York Irish from 1918 to 1958. It’s one of the most important periods,” says Quinn, when “the real process of Irish assimilation” took place.

It is also a time period of such rapid change that centuries, rather than decades, seem to pass.

Consider a scene from Hour of the Cat, where Dunne conducts an investigation on the West Side of Manhattan.

These days the West Side is a gleaming wonderland whose cafes and sidewalks are clogged with bustling businessman and European tourists. The wildly popular High Line park is an old elevated train track converted into an exotic walkway bursting with visitors and plant life.

But the West Side Dunne prowls transports us back to a time when the West Side was the heavily Irish and deeply impoverished neighborhood known as Hell’s Kitchen.

“The cobblestones on Twelfth Avenue were slippery wet. The hum of the highway overhead flowed like an electric current down the iron supports into the street. Behind a frayed corroded wire fence was a huddle of tarpaper shacks; beyond, on the mist shrouded river, the gigantic bulk of a passenger liner glided slowly towards the harbor’s mouth. The sudden, explosive blare of its horn momentarily drowned out the heckle of horns, whistles, bells, the argument of the New York waterfront.”

These scenes of Depression-era Hoovervilles in Hell’s Kitchen – like the entire trilogy – do what all of the best historical fiction does: bring the past back to life while also compelling us to make connections between the past and the present.

As Quinn puts it: “Historical fiction is a pack of lies in pursuit of truth.”

Politics and Religion

Over the course of Quinn’s trilogy, New York transforms from a depression-addled city to a gleaming metropolis undergoing a post-war boom.

“The wars were catalysts for social mixing and assimilation,” notes Quinn, whose Bronx-born father was a U.S. congressman and long-time judge.

“So was Prohibition. This was the first time the upper classes drank with lower classes. And it was the first time women drank with men. . . . The city is very different in the 1930s than it is in the 1950s.”

Quinn’s own life is intimately tied to New York City. His grandparents were Irish immigrants who settled on the Lower East Side, where his father was born.

Both of Quinn’s parents attended college, quite a rare feat for mid-century Irish Americans.

Catholic schools played a key role in the Quinn family’s achievements.

“My father felt a great debt to the De La Salle Christian brothers . . . they had bigger dreams for him that he didn’t even have for himself.”

Quinn, along with his twin brother, Tom, and two sisters, was raised in the Bronx.

Quinn’s father was elected to the New York State Assembly in the 1930s, and later to a term in Congress, before embarking on a long judicial career. Quinn’s parents, he said, were “big readers,” and the pre-Vatican II Church he grew up in, with its highly ritualized Latin mass, also encouraged a reverence for mystery.

“Everything is a mystery,” notes Quinn, whose readings of Raymond Chandler also inspired the Dunne books. “Marriage is a mystery, death is a mystery . . . it’s all a mystery.”

Quinn attended Manhattan College, but after graduation had trouble settling into a satisfying career. It was while he was working as a messenger on Wall Street that his father took him aside and reminded him of what had served generations of New York Irish Americans so well: civil service.

Quinn’s father strongly suggested he take an upcoming court officer’s test.

“I was not enough of a 1960s rebel to defy my father,” Quinn quipped.

Love of Stories

After a few years as a court officer, Quinn returned to school, completing all of the course requirements (though not the dissertation) for a doctorate in history from Fordham. An article by Quinn about the Irish ended up on New York governor Hugh Carey’s desk, which led to a job as a speechwriter – first for Carey, and then for Mario Cuomo.

After that, he worked as the editorial director for Time Warner. But politics and the corporate world were no match for the printed word.

“I always had a book in the drawer,” Quinn said, adding that he usually woke up in the wee hours of the morning to work on what would become Banished Children of Eve, before heading off to his day job.

“To love is to persist,” says Quinn, playfully adding that he chased his wife, Kathy, for 14 years before they were married. (They have two children.)

“My mother always told me as a kid: ‘Wherever you go, come back with a story.’ ”

Quinn adds: “The most important human occupation, I think, is storytelling. . . . What distinguishes us as a species is not just moveable thumbs. We’re the only storytellers. Every tribe, every nation, every family, every religion is a story.”

Thanks to Peter Quinn – not to mention Fintan Dunne and the expansive cast of Banished Children of Eve – the story of the Irish in America is much more rich and compelling.

Dear Peter:

It was eerie reading about your life because so much of it mirrors my own. I have a perennial historical novel out THE TRIAL OF BAT SHEA and I want to get you a copy, so if you can tell me where to send it.

I spent 23 years in the Capitol, in the Assembly for 7 with Rapp Rappelyea, then in the Senate with Joe Bruno. My father was a judge out of Rensselaer County who made it to the Appellate Division — Hugh Carey appointed him to that court even though he was Republican. Carey was a great guy and looked just like my grandfather.

If you can send me an address to jackcaseyj@aol.com I will mail you BAT SHEA and you can read a true story about how an Irish kid went to the chair for a murder he didn’t commit.

JACK CASEY

Dear peter:

I think i Met you once when I was a freshman at the Prep. I picked up looking for Jimmy and realized it was almost my own family story with parents arriving in 1939 from Mayo. Thank you for writing it

Best

Jim Thornton

Manhattan Prep 1971

Manhattan College 1974