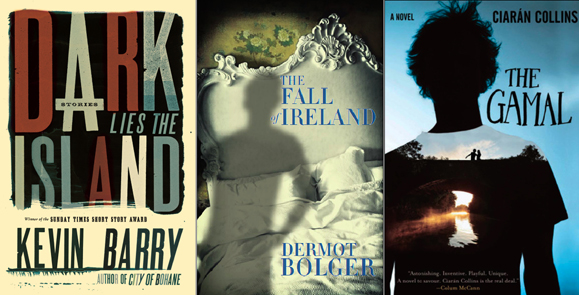

Dark Lies the Island

In Dark Lies the Island, Kevin Barry returns to the form that marked his literary debut (American readers who enjoyed his novel, City of Bohane, take note – his first short story collection, There Are Little Kingdoms, is also being released in the U.S. by Graywolf). Barry, born and raised in Limerick, has a singular voice and imagination. He is the rare writer who has you laughing at things you mightn’t otherwise find funny before you fully understand what’s happening. His humor is rarely gratuitous, however, and between the laughs he’s equally skilled at exposing seemingly mundane stories for how much they mean to the people who live them.

“Beer Trip to Llandudno,” which won the (U.K.) Sunday Times Short Story award, follows the six middle-aged men of the Merseyside Real Ale Club on their summer outing. “Across the Rooftops,” the first story in the collection, perfectly captures a fleeting moment that quietly goes less than perfect. Turning an eye to Celtic Tiger hysteria and the personal (in addition to economic) inflation that went with it, “Wifey Redux” toes the line between being a resounding example of “recession literature” and subtly making fun of the entire idea.

This delicate satire is something Barry excels at as he zeroes in on the hilarity and the dangers – especially the dangers – of small-town Irish ennui and insularity. In “Ernestine and Kit,” two old dears out for a Saturday drive are not at all what you’d expect. “Fjord of Killary” upends the romanticism of the West of Ireland, with a disappointed poet narrator, a bar full of eccentric but immediately recognizable locals, and a staff of resentful Belarusian teens all facing an apocalyptic flood. The collection has its quieter moments too, in “A Cruelty,” which follows a young mentally challenged man on his daily routine, and “The Mainland Campaign,” which peers inside the mind and motivations of a young IRA bomber in training in London.

In short, Dark Lies the Island achieves what any good story collection strives to, displaying Barry’s vast range of talent and writerly moods. The final story, “Berlin Arkonaplatz – My Lesbian Summer,” combines them all, and provides a glimpse into Barry’s artistic salad days, in a powerful ode to a friend long gone but not forgotten.

(Graywolf Press / $24.00 / 192 pages)

The Fall of Ireland

In his latest novella, Dermot Bolger sets out to tackle the mentality of Ireland’s fall from trumped-up Celtic Tiger glory into recessionary, IMF-controlled disgrace. A brief but potent volume of 113 pages, The Fall of Ireland is an intimate psychological portrait of Martin, a middling civil servant on a keeping-up-appearances St. Patrick’s Day visit to Beijing. There, his sole purpose is to ensure his Junior Minister seems important and to make his counterparts in the lower levels of the Chinese government feel as though they are being heard.

For Martin, things are less than rosy back in Ireland. While he has a loving relationship with his three teen-age daughters (and – unlike his neighbors – the satisfaction of actually owning his house and never investing in a deluxe rental in Bulgaria) he is increasingly estranged from his wife, Rachel, who, in trying to find herself after accepting an early retirement package, has decided that she no longer cares for Martin on an emotional or physical level.

During some downtime in his luxury hotel room, he is alone with his thoughts. In a form of rebellion that would be of little consequence to some but is a big deal for Martin, he calls a masseuse to his room. She makes him aware of what he wants and what he will never have.

Heavy-handed at times (it may have been best to leave it to the reader to conclude that “his fall had been as abrupt and humiliating as the fall of Ireland”), the novella is still worth delving into as the cry of a writer who has seen his country hurt and taken up his pen (or keyboard) in response. Rich in detail, it is a believable portrait of a person and a state of mind we all know.

(Island Press & Dufour Editions / $23.95 / 114 pages)

The Gamal

Ciarán Collins, a secondary school teacher from West Cork, made his literary debut in July with The Gamal. The novel is brilliant, a sign of more inventive things to come from a writer with powerful imagination, empathy, and a cutting sense of humor.

Collins’s narrator is Charlie, 25, from the fictional (but very real) town of Bally-ronan, Co. Cork. Charlie has Oppositional Defiant Disorder, which means, as he puts it, that he “doesn’t give a fuck.” Assuming him to be “a bit of a ‘God help us,’” the town calls him the Gamal, short for the Irish “gamallogue,” which roughly translates to fool or idiot. They let their guards down around Charlie, who doesn’t miss a thing.

The only people Charlie really ever liked (and the only ones who saw his true worth) were his friends Sinead O’Riordan and James Kent. In love for as long as anyone in the town could remember, they were a talented musical duo with sights set on Dublin and then the U.S. From the start of The Gamal we know that something tragic has happened to them involving a bridge, a death, a court case and national media attention. Charlie, suffering from PTSD, has been assigned by his therapist, Dr. Quinn, to write 1,000 words a day to help him process awful events from five years ago.

Charlie is a reluctant writer at first, copying and pasting things from the Internet to meet the daily quota. These insertions continue throughout, as Charlie adds photos, drawings, court transcript excerpts and asks the reader to write in song lyrics (on blank lines he provides) to save him from “pay[ing] the people who made up the songs millions to put the words in my book.” Far from post-modernly precious, these elements bring a great sense of connection to the book and force the reader to pause, to really think about what Charlie (and Collins) wants them to.

The Gamal is a riveting, sometimes terrifying, and heartbreaking look at insidious small-town jealousy and the things people do for love.

(Bloomsbury / $18.00 / 408 pages)

For a refreshing review of Dermot Bolger’s “The Fall of Ireland”, click on

http://www.davidmurph.wordpress.com/book-reviews/