Writing from his mother’s perspective, Jim Dette pays tribute to the memory of his grandfather Jim Burke.

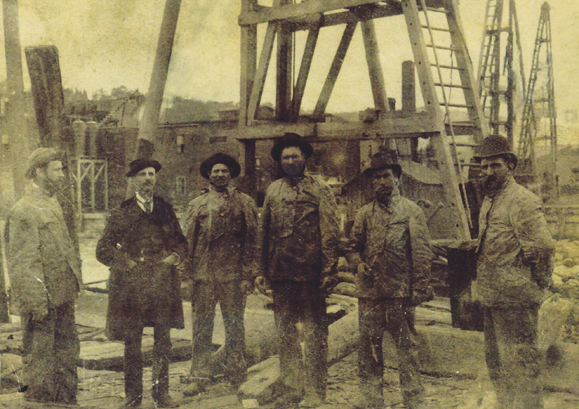

My son has been after me to write down some of the remembrances of my father I’ve shared with him over the years. Before it’s too late, I’m sure he’s thinking. He keeps referring to an old, faded photograph of a group of refinery workers. It’s one of the few I have of my father. But the loving memories I have of him have left an indelible portrait in my mind.

There was, for example, the respiratory illness I contracted as a child. The doctor had recommended a sea voyage.

“A sea voyage!” Ma exclaimed. “Can you imagine? A stationary fireman with six kids. Where is he going to get the money?” Well, he had a solution. He would bundle me up and take me from our home in Garfield, New Jersey, to Battery Park in New York City to spend the day sitting on a bench and walking the waterfront.

I remember it so well. It’s the spring of 1899. We’re getting on the train in Garfield, sandwiches in his lunch pail and a blanket to wrap me in as we take the sea air. He’s dressed in his Sunday best: a dark suit, white shirt, and tie. A woolen scarf and derby guard against the late March breezes. I’m wearing a hand-me-down blue woolen coat from my sister Mame. A knitted gray scarf and a matching hat, pulled down over my ears, protecting me from the breezes.

After the twenty-minute ride on the Erie Railroad comes the ferryboat to Cortlandt Street. We stay inside. He doesn’t want to overdo it on the first trip. We walk toward the Battery. He holds me tightly by the hand as we pass the busy docks: longshoremen unloading mahogany and ingots of tin from the Congo, the teamsters tending their horses as they wait their turn to board the ferry at Liberty Street. It’s an exciting experience for an eight-year-old. Maybe too exciting. The effects of the illness slow me down. No trouble for a man who shovels coal all day. Up on his shoulders, I go for a quick walk to Broadway, where we take a trolley to the end of the line.

We find a bench near the water. He wraps me in the blanket, and we settle down for our ‘sea voyage.’ “You look just like one of those swells on the first class deck,” he says, admiring his little passenger. “I think the captain’s ready to sail. All ashore that’s going ashore,” he adds to complete the game.

I’m soon absorbed in the sights of the harbor. The big ferries leave regularly for Staten Island. A group of excited tourists board a small launch for the Statue of Liberty. “Could we go someday?” I ask. We plan an excursion for the whole family.

He takes out a cigar and lights it. As the smoke drifts away, he gazes out at the Statue of Liberty. It wasn’t there that March day in 1870 when he first saw this harbor from the deck of a steamship out of Cobh. He was fourteen and worried that his older brother wouldn’t be there. But Uncle William was there and whisked him away to Jersey City and a job the next morning. They all come through Ellis Island now, with the Statue of Liberty to greet them.

Life’s been good to him. He married Annie Curry in 1880. ‘Ah, Annie, how did she ever go for a greenhorn like me?’ he thinks and smiles at the thought of his outspoken American-born wife.

“Annie,” he says, turning his attention back to me, “shall we see what your ma has made us for lunch?” He opens the pail he carries every day to work and hands me one of the sandwiches.

My eyes brighten. “Oh, meatloaf!” I exclaim.

“Yes, your Ma knows what you like,” he says, seeing my eyes light up. “God bless you, Annie. You never let anything get you down.”

We eat in silence, watching the gulls scrambling for the pieces of bread we throw to them. When we finish, he asks, “Would you like to go to the ferry terminal for a cup of tea?” I struggle out of the blanket in response. We fold it up and walk through the yawning entrance of the large building. The cafe ceiling seems to stretch up to the sky. Along the far side of the room runs a long, marble-topped counter; behind it stands a dazzling array of coffee urns, glass cases with assorted pastries, fruits, beverage bottles, and a variety of sandwiches. Waiters stand ready to serve the few customers seated on tall chairs with wire legs and backs shaped like hearts. Since the Saturday crowd is light, we quickly find seats at one of the marble-topped tables with chairs matching those at the counter.

A waitress appears, and he orders tea. She turns and asks, “And what will you have, miss?”

“Tea,” I blurt out.

“Will that be all?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he says, and then, as an afterthought, “Would you be havin’ any scones?”

“I’ll see.” The waitress returns with a steaming pot of tea, a creamer, a sugar bowl, and a plate with two of the biscuits. “Tea for the lady,” she announces as she sets a cup and saucer before me with an extra flourish, “and tea for the gentleman. I’m sorry, there were only these two left from the breakfast.”

“That will do fine,” he answers.

“Ma! Ma! It was grand! We watched the ferries, and there were these big boats coming in, and we watched seagulls, and there was this big sailboat that came around from the East River, and we went to this fine restaurant for tea and scones.”

“Tea and scones is it. Aren’t we the fancy ones?” my mother says, smiling up at my father just now entering the kitchen. “And I suppose next week it will be steak, potatoes, and Pluto water at Delmonico’s. And how is my little Annie?” she asks, bending over to help me off with my coat.

“Fine, Ma, fine.”

So the days went. Every Saturday for a month and a half we made the ‘sea voyage.’

And I got better.

Note: Jim Dette, of Weehawken, New Jersey recorded his mother’s memories of her father’s efforts to help her heal from the respirtatory illness she had as a child. Published in October/November 2013 issue

Leave a Reply