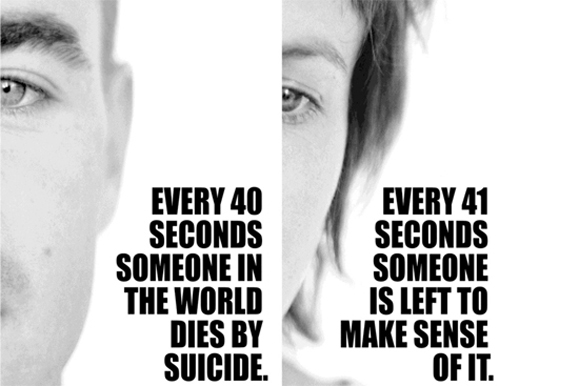

Suicide in Ireland, particularly among male teens, is on the rise. Sharon Ní Chonchúir reports.

Few teenagers make a mark on Irish society in the way 16-year-old Tralee native Donal Walsh did. Having battled cancer on three separate occasions, Donal finally succumbed to the disease in May. But before he died, he spread a serious message. He spoke out urging people, especially young people his age, not to commit suicide.

“I was given a timeline on the rest of my life,” wrote Donal in an open letter. “No choice, no say, no matter… I couldn’t believe all I had was 16 years here and I began to pay attention to every detail that was going on in this town. I realized I was fighting for my life for the third time in four years and this time I have no hope. Yet I still hear of young people committing suicide and it makes me feel nothing but anger. I feel angry these people choose to take their lives and here I am with no choice.”

Donal took to the national airwaves with his message and even made a memorable appearance on The Late Late Show. He’s not the only one to have spoken out about suicide in Ireland either. Irish-American comedian Des Bishop made reference to it in his latest TV documentary Under the Influence when he linked Ireland’s high alcohol consumption with high rates of suicide in the country.

But what exactly is the situation with suicide in Ireland? Is it as worrying as both Donal and Des maintain?

In Ireland, approximately 500 people commit suicide every year, a figure that gives us the sixth lowest suicide rate in the EU (Greece has the lowest and Lithuania has the highest).

However, many people who work in the field of mental health believe that suicide figures are underreported and that the true figure from Ireland is likely to be closer to 700 a year.

“That’s two people every day,” says Noel Smyth, Chairman of Turn the Tide of Suicide, “3Ts,” a charity founded in 2003 to raise awareness of the problem of suicide in Ireland and to raise funds for research, educational support and intervention.

“It’s three times the rate of people who die on our roads,” he continues. “We have made dramatic inroads into what used to be described as ‘the carnage on our roads,’ where we have seen young male driving deaths reduced by 50%. This has not been attained by accident. Surely this model can be embraced in our fight against suicide and a dedicated Suicide Prevention Authority can finally begin to turn the tide of suicide.”

In a 3Ts report called Suicide in Ireland published in May this year, Dr. Kevin Malone, a Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Mental Health at University College Dublin, looked at 104 Irish families bereaved through suicide between 2003 and 2008 and found worrying results.

It was already common knowledge that most suicide victims are male, roughly 80%; what people hadn’t realized is how serious the problem was among younger men.

Dr. Malone’s report found that suicide was the leading cause of death for young men in Ireland and that the country was the fourth highest in the EU in the 15-to- 24-year-old age group. By analyzing almost 12,000 suicide deaths in those aged 35 and under, the report identified a four-fold accelerated suicide count up to age 20, leveling off from the age of 21 onwards.

“John B. Keane wrote his famous play Many Young Men of Twenty Said Goodbye, about young men heading off to war,” Dr. Malone says. “Fifty years later, suicide is our war for young men.”

Families interviewed for the report stated a general lack of satisfaction with the treatment given to their loved ones before they died and the services they received in the aftermath of their deaths. Sixty-six percent reported dissatisfaction with health services, 20% with justice services and 8% with education.

Case studies included a family whose son had been “stitched up in A&E, given a month’s prescription and sent home” after trying to commit suicide, and another family with a suicidal youngster being sent to another hospital with a note that read “sorry, not our area.”

For the first time in Ireland, the report also identified the true extent of suicide clusters. “I think this has been previously under-estimated,” says Dr. Malone. “Our findings suggest that up to 50% of our under-18 suicide deaths in Ireland may be part of couplets or clusters. A young suicide is a powerful and destabilizing social force that can reverberate intensely.”

This report isn’t the only worrying recent finding. A 2011 Mental Health Barometer conducted by pharmaceutical firm Lundbeck found that stigma and embarrassment still surround depression in Ireland. Forty-two percent of those interviewed said they would not want someone close to them who is dealing with depression reaching out to them for help, although they did acknowledge that talking and having someone listen is a step towards recovery.

We can conclude then that Ireland has a problem. But what is being done about it? Who, apart from Donal Walsh, Des Bishop and 3Ts, is speaking out and trying to do something?

Console, the national suicide charity, is backing some of the recommendations made in Dr. Malone’s report. They are especially interested in his call for the creation of a real-time database for teen and young adult suicides.

“We need to find out why these trends are happening, but the figures we have are provisional when what we need is accurate and timely data,” says Ciarán Austin, Director of Services with Console. “We need significant changes and investment in research, as the lack of accurate information is impeding our ability to understand and respond to the awful tragedy of suicide. If we could identify trends and clusters, this would help agencies and services to understand the specific problems and, hopefully, to respond sooner.”

Aware, an organization that provides support, information and education about depression and related conditions, takes the view that the threat of suicide is increased in times of recession.

“There may be an increased sense of hopelessness for the future in challenging times like this,” says Aware’s Sandra Hogan. “This can impact especially on people who may already be vulnerable.”

Aware are calling on the government to increase funding for mental health services. “They need to be more widely available and more accessible,” says Sandra. “There is also a need for a sustained positive awareness campaign highlighting mental health, how to look after it and the sources of support that are available.”

Recognizing that the national budget may not be able to stretch to such services and campaigns, Sandra also emphasizes peoples’ personal responsibilities. In what could be seen as a retort to the Lundbeck Mental Health barometer findings, she says that mental health needs to be normalized. “People need to be able to talk more openly and responsibly about it,” she says. “This would ultimately help people to find it easier to reach out for the help that is available when they need it.”

If that’s what mental health organizations would like to see the government doing, what are they actually doing at the moment? The National Office for Suicide Prevention (NOSP) is in charge of the implementation, monitoring and evaluation of “Reach Out” – the national strategy for action on suicide prevention 2005-2014. In this ten-year plan the NOSP works with more than 50 agencies and organizations nationwide.

“Partnership is the foundation to effective suicide prevention work in Ireland,” says Michelle Merrigan on behalf of the NOSP. “Suicide prevention is best achieved when individuals, families, health and community organizations, workplaces, government departments and communities work collaboratively to build an infrastructure of suicide prevention and support from local through to national level.”

In 2011 (the last year for which information has been collated), the NOSP had several key achievements. They allocated €1million extra to 22 new projects including training programs for frontline medical staff and improving intervention services for people who engage in suicidal behavior. They developed “Your Mental Health,” a campaign involving radio advertisements and a website that focussed on the importance of good mental health. And they also started work on responding to suicide clusters and developing national guidelines for post primary schools on mental health and suicide prevention.

However, their work has only just begun and in the meantime, organizations such as Console and Aware, academics such as Dr. Malone and committed individuals such as Donal Walsh and Adam Harris are trying to fill the gaps.

Eighteen-year-old Adam from Greystones in Wicklow designed the GraspLife phone app after witnessing the effect of suicide on his own community. His app enable users to find help in their locality quickly by bringing together all contact details for organizations such as Aware, The Samaritans and Console.

Adam is currently in talks with Three (one of Ireland’s largest mobile phone providers) about pre-installing the app on all new handsets.

“People are embarrassed to talk about mental health with their friends and they don’t know where to go,” says Adam. “I wanted a resource they could use discreetly that had all of the information from Ireland’s largest charities in one place.”

The statistics show that Ireland has a suicide problem. A cursory glance at the figures implies that we compare favorably with other EU countries but in-depth investigation belies this. Irish men and particularly young Irish men have a higher risk of suicide than those in other countries, and more needs to be done to address this at an official level.

All of the organizations working to tackle the problem of suicide and all government departments should be spreading Donal Walsh’s message: “As a 16-year-old who has no say in his death sentence, who has no choice in the pain he is about to cause and who would take any chance at even a few more months on this planet, appreciate what you have. Know that there are always other options and help is always there.”

Sharon Ní Chonchúir lives and works in West Kerry. Much of her writing is concerned with the changing face of modern Ireland.

Leave a Reply