The history of medicine spans millennia – from before the invention in 5th century Greece of the Hippocratic oath, which doctors still take to this day, to the life-changing breakthroughs of the 21st century. The following pages share the stories of some of the most important, illustrious and idiosyncratic Irish and Irish Americans in the history of medicine, from the inventor of the defibrillator to the surgeon who performed the first successful kidney transplant, and beyond.

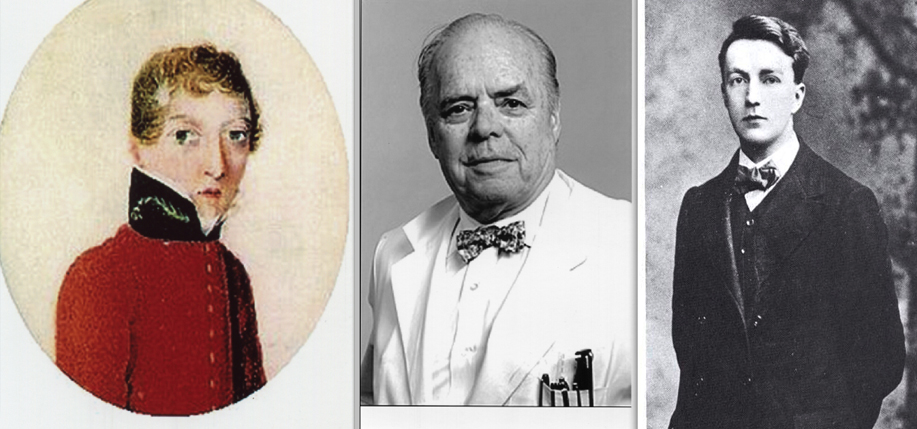

Dr. James Barry

One of the most fascinating figures in medical history, Dr. James Barry was a military surgeon in the British Army who rose to the rank of Inspector General of military hospitals. Among Barry’s many achievements were the improvement of conditions for wounded soldiers, and the first caesarean section operation in Africa to see the survival of both the mother and baby. Upon his death from dysentery in 1865, it was discovered that Dr. Barry was in fact a woman, a secret she had hidden her whole life, and one that made her the first woman in the British Isles to qualify as a doctor.

One of the most fascinating figures in medical history, Dr. James Barry was a military surgeon in the British Army who rose to the rank of Inspector General of military hospitals. Among Barry’s many achievements were the improvement of conditions for wounded soldiers, and the first caesarean section operation in Africa to see the survival of both the mother and baby. Upon his death from dysentery in 1865, it was discovered that Dr. Barry was in fact a woman, a secret she had hidden her whole life, and one that made her the first woman in the British Isles to qualify as a doctor.

Accounts vary of her early years, but the general consensus is that Dr. Barry was born in Ireland around 1790, the second child of Jeremiah and Mary-Ann Bulkley, and was named Margaret. Her mother was the sister of famed Irish painter James Barry. With Jeremiah in prison and Margaret’s older brother married and estranged, she and her mother were left to fend for themselves. A series of correspondences with the family’s lawyer has led historians to conclude that in 1809 Margaret disguised herself as a boy, assumed the name James Barry, and sailed with her mother to Scotland, where she enrolled in the medical school at the University of Edinburgh, and lived as a man from there on.

Barry qualified as an MD in 1812 and moved to London where he continued his studies. In 1813, he took the examination for the Royal College of Surgeons of England and qualified as a Regimental Assistant, taking up posts in Chelsea and Plymouth, and then India and South Africa. Further promotions would take Barry around the world: to Mauritius, Trinidad and Tobago, Malta, Corfu, the West Indies, Jamaica and Canada. He was known for his advocacy of improvement of living and hospital conditions for women, children, soldiers and the poor, but also for his tendency to ruffle feathers of those in local politics. Barry retired – reportedly against his wishes – in 1864. After the discovery of Barry’s sex, the British Army sealed all records relating to him for 100 years. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery under the name James Barry, and with full rank. – Sheila Langan

The Fitzpatrick Factor

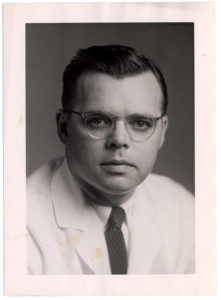

The father of modern academic dermatology and a giant in the advancement of clinical and investigative dermatology, Dr. Thomas B. Fitzpatrick was born in Madison, Wisconsin on December 19, 1919. Fitzpatrick went on to serve nearly 30 years as the chairman of the Department of Dermatology at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Dermatology Service at Massachusetts General Hospital. His contributions to the field were tremendous: his renowned multi-author book Dermatology in General Medicine is used to this day; he was a passionate teacher and trainer, and his discoveries and research led to therapies that combat psoriasis and forms of skin cancer. His innovative pursuits led to more effective treatment of skin diseases.

The father of modern academic dermatology and a giant in the advancement of clinical and investigative dermatology, Dr. Thomas B. Fitzpatrick was born in Madison, Wisconsin on December 19, 1919. Fitzpatrick went on to serve nearly 30 years as the chairman of the Department of Dermatology at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Dermatology Service at Massachusetts General Hospital. His contributions to the field were tremendous: his renowned multi-author book Dermatology in General Medicine is used to this day; he was a passionate teacher and trainer, and his discoveries and research led to therapies that combat psoriasis and forms of skin cancer. His innovative pursuits led to more effective treatment of skin diseases.

Dr. Fitzpatrick received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Wisconsin and went on to graduate with an MD from Harvard Medical School. He interned at Boston City Hospital and it was there that he recognized a significant imbalance of priority between dermatology and other medical specialties. It became Fitzpatrick’s quest to remedy that imparity. At the University of Minnesota, where he earned his PhD in Pathology, Fitzpatrick met fellow MD and PhD Adam Lerner, with whom he conducted substantial research on skin pigmentation that led to ultraviolet light therapies to treat psoriasis and other severe skin diseases. Fitzpatrick continued advancing his knowledge and took up dermatology training at the University of Michigan and the Mayo Clinic. At 32, he was recruited by the University of Oregon to be Professor and Chair of Dermatology. Harvard would invite him only seven years later to assume the chair of the Dermatology Department. At 39, he became the youngest professor and chair at Harvard.

Among his scientific contributions are the Fitzpatrick Scale, developed in 1975 and used to this day, a numerical classification of skin color and how UV rays affect different skin tones. This discovery led to his quantitative research of the effectiveness of sunscreen. He also helped establish clinical criteria that improved the diagnosis of malignant melanoma, and his research on the epidermal melanin unit fundamentally changed modern dermatology’s understanding of skin pigmentation. Fitzpatrick passed away in Massachusetts in 2003 at age 83. – Michelle Meagher

Oliver St. John Gogarty

“Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and razor lay crossed.” James Joyce’s Ulysses begins with this comic representation of his contemporary Oliver St. John Gogarty. This solidified the public persona of Gogarty, an accomplished Irish writer, poet, politician, athlete and wit. While he is best known for his connections with W. B Yeats, Arthur Griffith, and Joyce; his own writing; and his political initiatives for Ireland, Gogarty’s greatest immediate contribution to Ireland was his career in medicine as a successful otolaryngologist.

“Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and razor lay crossed.” James Joyce’s Ulysses begins with this comic representation of his contemporary Oliver St. John Gogarty. This solidified the public persona of Gogarty, an accomplished Irish writer, poet, politician, athlete and wit. While he is best known for his connections with W. B Yeats, Arthur Griffith, and Joyce; his own writing; and his political initiatives for Ireland, Gogarty’s greatest immediate contribution to Ireland was his career in medicine as a successful otolaryngologist.

Gogarty’s passion for medicine was passed down to him by his father and grandfather, who were both medical doctors. He was raised Catholic, but due to his family’s affluence was able to gain access to influential schools where Catholics normally were not permitted. He was an accomplished athlete, playing soccer, cricket, and cycling while studying medicine at the Royal University of Ireland and Trinity College, Dublin. Gogarty also relished the bohemian underbelly of Dublin. Under the wing of John Pentland Mahaffy, a former tutor of Oscar Wilde, he was swept away by poetry and literature, publishing poems and stories in various Dublin journals.

In 1906 Gogarty married Martha Duane and by 1907 had passed his medical examinations, receiving both an MB and MD. Gogarty left Ireland to continue training in Vienna with Sir Robert Woods, a specialist in otolaryngology (ear, nose and throat medicine), an area Gogarty would himself master upon returning to Dublin and securing a post at Richmond Hospital in 1908. By 1912, he was a successful surgeon at Meath Hospital where he showcased his love of the theatrical by spouting clever witticisms while operating on patients both wealthy and not, some of whom he saw free of charge. Gogarty’s practice also influenced his political outlook, leading him to see sectarianism as a detriment to Irish health care as it prevented the centralization of medical services.

In the early 1920s, Gogarty became active in the Irish Free State, as a senator and a friend of Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, whose autopsies and embalmments he later performed. He was kidnapped in 1922 by a group of anti-Treaty militants, but narrowly escaped. After Renvyle, his estate in Galway, was burnt down some months later, he moved his family and his practice to London, but returned to Ireland in 1924. Gogarty remained a senator until 1936, after which he devoted the rest of his life to writing. He tried enlisting to fight in the RAF in WWII, but was denied due to age. After a lecture tour of America in 1939, Gogarty settled in New York, where he wrote novels and early reminisces of his life in Ireland until his death in 1957. – Matt Skwiat

Dr. Robert James Graves

Dr. Robert James Graves only lived 57 years, but in his lifetime brought more permanent change to the Irish medical system than perhaps any other doctor. He is best remembered for the first comprehensive description of Graves’ disease, an autoimmune disorder that causes enlargement of the thyroid gland, affecting mood, weight, and mental and physical energy levels. Though not the first to note it, in 1835 Dr. Graves was the first doctor to recognize the full symptomatology of Graves’, specifically the correlation between exophthalmos (bulging eyeballs) and an enlarged thyroid. Subsequently, the disease was named after him by famed French physician Armand Trousseau. Although his name most notably lives on in this form, his credits range far beyond that of a namesake.

Dr. Robert James Graves only lived 57 years, but in his lifetime brought more permanent change to the Irish medical system than perhaps any other doctor. He is best remembered for the first comprehensive description of Graves’ disease, an autoimmune disorder that causes enlargement of the thyroid gland, affecting mood, weight, and mental and physical energy levels. Though not the first to note it, in 1835 Dr. Graves was the first doctor to recognize the full symptomatology of Graves’, specifically the correlation between exophthalmos (bulging eyeballs) and an enlarged thyroid. Subsequently, the disease was named after him by famed French physician Armand Trousseau. Although his name most notably lives on in this form, his credits range far beyond that of a namesake.

Born in 1796 to a wealthy Anglo-Irish Dublin family of Cromwellian-era descent, Graves graduated with a medical degree in 1818 from Trinity College Dublin (where his father and maternal grandfather were both Senior Fellows) and proceeded on a three-year tour of medical schools on the continent that left a profound impact on his pedagogical style.

Known as a bit of a rake, at times rambunctious and avant-garde, Graves returned to Ireland in 1821 eager to implement what he had seen abroad. He became chief physician and lecturer at Meath Hospital, where he was responsible for two major achievements. First, Graves eschewed Latin-language medical lectures, which were then still common practice, in favor of English lectures, making the subject more accessible to students. Then, having seen students participate in doctors’ rounds at patients’ bedsides in Germany, he resolved to introduce that method of learning. Under Graves, students were able to observe patients in the hospital, ask questions, and assist the primary physician in diagnoses and treatment plans.

Graves was one of the first Irish doctors to promote the use of the stethoscope, which was invented in France in 1816, and is also purportedly the uncredited inventor of fixed second hands on watches. Allegedly, he developed the second hand to be used in conjunction with the stethoscope to measure heartbeats per minute and is said to be the first doctor to use the method to measure heart rate.

A profile of Dr. Graves in volume 19 of Dublin University Magazine, published in 1842, calls him “the first great medical teacher we have had in this country,” and welcomes his arrival on the medical stage as “a new light.” Though he died from liver cancer in 1853 (apparently before he could patent the second hand), Graves was undoubtedly a pioneer in his field. He brought the latest advancements from the continent to the more conservative English-speaking schools and ushered in a new era of medical learning in Ireland. – Adam Farley

Charles McBurney

Anyone who has ever suffered the pain of appendicitis is familiar with the term “McBurney’s point,” the area on the right side of your abdomen where your appendix can be found. Discomfort from light pressure applied to this area is a sign of appendicitis. Charles McBurney, the doctor for whom the point is named, was one of the preeminent surgeons of nineteenth century medicine.

Anyone who has ever suffered the pain of appendicitis is familiar with the term “McBurney’s point,” the area on the right side of your abdomen where your appendix can be found. Discomfort from light pressure applied to this area is a sign of appendicitis. Charles McBurney, the doctor for whom the point is named, was one of the preeminent surgeons of nineteenth century medicine.

Dr. McBurney was born in 1845 in Roxbury, Massachusetts. McBurney’s father, Charles, was a native of the north of Ireland and had immigrated to the United States when he was a boy. McBurney’s mother, Rosine, was a native of Massachusetts with Scottish ancestry, who together with her husband provided a remarkable education for their young son. He was trained in the Roxbury Latin School and other elite private schools around Boston, and would eventually attend Harvard. He graduated from Harvard in 1866 and entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City, receiving his MD in 1870. After completing an internship with Bellevue Hospital he traveled abroad, continuing his studies in Vienna, Berlin, Paris, and London.

Upon returning to the States in 1872, McBurney became assistant demonstrator of anatomy at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York. McBurney’s knowledge of and respect for the medical profession secured him various positions in hospitals around New York in the 1880s and 90s, including St. Luke’s, Bellevue, and Roosevelt hospital. While working as a surgeon at Roosevelt Hospital in 1892, McBurney established the Dyms Operating Pavillion, a facility that specialized in surgical teaching and research. One of McBurney’s other specialties was research for and treatment of the appendix. In 1894, he described the incision which now bears his name, but which was first described by Louis MacArthur. In addition to the appendix, McBurney published work on gallstones and shoulder dislocation. When President William McKinley was shot in 1901, McBurney was among the consulting surgeons.

McBurney continued to work until the end of his life, becoming a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh and publishing numerous articles in the medical field. He died in 1913 at the age of 68, but left behind a prestigious array of work that solidified his prominence in the medical world. – Matt Skwiat

James McHenry

Arriving on the shores of the American colonies in 1771, the young Irishman James McHenry embarked on a life of patriotic zeal and noble medical prowess. Born in Ballymena, County Antrim, Ireland in 1753 to a prosperous mercantile family, McHenry had a prominent upbringing, receiving a classical education in Dublin. McHenry journeyed to the American colonies in 1771, the first member of his family to do so. He began a career in medicine, another first for his family, and studied at the Newark Academy in Delaware (later the University of Delaware). From there, McHenry relocated to Philadelphia, studying for two years under Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and member of the Continental Congress. McHenry gained from Rush both a love for the medical profession and a patriotic fervor for his new home. This led him to volunteer as a military surgeon at Cambridge hospital in Massachusetts when hostilities broke out in 1775.

Arriving on the shores of the American colonies in 1771, the young Irishman James McHenry embarked on a life of patriotic zeal and noble medical prowess. Born in Ballymena, County Antrim, Ireland in 1753 to a prosperous mercantile family, McHenry had a prominent upbringing, receiving a classical education in Dublin. McHenry journeyed to the American colonies in 1771, the first member of his family to do so. He began a career in medicine, another first for his family, and studied at the Newark Academy in Delaware (later the University of Delaware). From there, McHenry relocated to Philadelphia, studying for two years under Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and member of the Continental Congress. McHenry gained from Rush both a love for the medical profession and a patriotic fervor for his new home. This led him to volunteer as a military surgeon at Cambridge hospital in Massachusetts when hostilities broke out in 1775.

As military surgeon of the Continental Army, McHenry proved resourceful in both his care of wounded patients and bravery on the field. In 1776, McHenry, then surgeon of the 5th Pennsylvania Battalion, was captured by the British along with 5,000 other soldiers at Fort Washington. While imprisoned he cared for the sick and wounded in the prison, writing of the cruel and meagre conditions that the prisoners were confined to, concluding that it “made up altogether a scene more affecting and horrid than the carnage of a field of battle wherein no quarter is given.”

McHenry was exchanged and put on parole in 1778, later joining General George Washington’s staff in 1780 and striking up a lifelong friendship with the Marquis de Lafayette. He entered the Maryland senate in 1781 and served in the Continental Congress, becoming a signer of the Constitution, one of only three physicians and four Irishmen to do so. He continued serving in the Maryland senate until 1796 when Washington made him Secretary of War. McHenry would hold his post until he was relieved by President John Adams in 1800, but during that time he had reorganized the United States Army and established the Department of the Navy.

McHenry spent his remaining years in retirement living in Fayetteville in Maryland. He died in 1816, leaving behind an indelible print on the trajectory of early American history and medicine. – Matt Skwiat

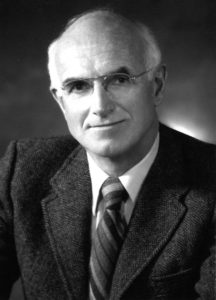

Joseph Murray

A pioneer in the field of transplant surgery, Joseph Edward Murray was the surgeon responsible for the first kidney transplant, the world’s first successful allograft, and the first ever cavaderic renal transplant. In 1990 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Murray was born in 1919 and grew up in Milford, Massachusetts in a family of Irish and Italian heritage. He attended College of the Holy Cross, studying English and philosophy, and then received his medical degree from Harvard. He fulfilled his military service in the plastic surgery unit at Valley Forge General Hospital in Pennsylvania, where he worked with Dr. Bradford Cannon on reconstructing the faces and hands of soldiers wounded in WWII, inspiring Murray’s life-long interest in transplant and plastic surgery.

Murray was born in 1919 and grew up in Milford, Massachusetts in a family of Irish and Italian heritage. He attended College of the Holy Cross, studying English and philosophy, and then received his medical degree from Harvard. He fulfilled his military service in the plastic surgery unit at Valley Forge General Hospital in Pennsylvania, where he worked with Dr. Bradford Cannon on reconstructing the faces and hands of soldiers wounded in WWII, inspiring Murray’s life-long interest in transplant and plastic surgery.

At Peter Brent Bringham Hospital (now Bringham and Women’s Hospital) in Boston, he performed the world’s first successful kidney transplant in 1954, between identical twins Ronald and Richard Herrick. In 1959 he completed the first successful transplant from a non-related donor, and three years later the first kidney transplant from a deceased organ donor. A leader in the field of transplant biology, he later worked with scientists to develop the immunosuppressive drugs that allow bodies to accept donations from unrelated donors. Murray also went on to teach at Harvard Medical School and served as the chief plastic surgeon at Bringham and Women’s and Children’s Hospital Boston before retiring in 1986. In 2001, he published his autobiography, Surgery of the Soul: Reflections on a Curious Career.

Following a stroke, Murray passed away in November 2012, aged 93 at the same hospital where he made history 58 years earlier. – Sheila Langan

Sister Anthony (Mary Murphy O’Connell)

Dubbed the “Irish Florence Nightingale” and the “angel of the battlefield,” Sister Anthony was one of the best-known names of the American Civil War and the 19th century medical field who devoted her life to caring for orphans, the elderly, new mothers and babies, and war-wounded soldiers in the field. She was also responsible for creating some of the first programs for training female nurses.

Dubbed the “Irish Florence Nightingale” and the “angel of the battlefield,” Sister Anthony was one of the best-known names of the American Civil War and the 19th century medical field who devoted her life to caring for orphans, the elderly, new mothers and babies, and war-wounded soldiers in the field. She was also responsible for creating some of the first programs for training female nurses.

Born Mary Murphy O’Connell in 1814 to Limerick farmers William and Catherine O’Connell, little is known of her early life. Sometime in the 1820s, the family immigrated to Boston and settled in the growing Irish community of Charlestown. Mary was enrolled in the prestigious Ursuline Convent Academy, a small Catholic secondary school, and in June of 1835, at age 21, joined the convent of the American Sisters of Charity in Emmitsburg, Maryland. Shortly after taking her final vows two years later, she was assigned to St. Peter’s Orphan Asylum in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Under Sister Anthony’s leadership, the Cincinnati Sisters founded St. John’s Hotel for Invalids (now St. John’s Hospital), an alternative retirement home and hospital, and later a new orphanage called St. Joseph’s in 1854. Sister Anthony was elected procuratrix of St. John’s when it was founded, and was the director of St. Joseph’s for about a year before devoting her attention to running St. John’s, where she inaugurated a visiting nurses training program.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Sister Anthony had nearly 25 years of medical training behind her and enlisted her fellow Sisters of Charity to volunteer at the nearby Union Camp Dennison during a measles outbreak. By 1862, Sister Anthony was more often on the field than off and had earned praise from Generals George C. McClellan and Ulysses S. Grant. During Grant’s campaign along Kentucky’s Cumberland River, Sister Anthony introduced the first recognizably modern triage tactics by ordering the most gravely wounded soldiers off the field first to be treated by doctors on the “floating hospitals” along the river. The less severely wounded soldiers were cared for on the field by nurses. Her medical knowledge and innovations led her to be hand-selected by the famed American surgeon George Curtis Blackman as his personal assistant at the Battle of Shiloh in April, 1862. In September, 1862, at the request of the U.S. Sanitation Commission, the Catholic Church officially assigned Sister Anthony to the Army of the Cumberland.

After her military service, Sister Anthony returned to her post at St. John’s. According to one historian, “she made no distinction between Union and Confederate soldiers; she only saw the extent of the wound,” earning her commendations by both President Lincoln and Jefferson Davis. Though she died in 1897, a 2003 Pentagon report gives testament to her enduring legacy, explaining that “her innovative triage techniques remain standard practices in every theater of war where American troops fight.” – Adam Farley

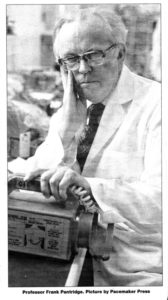

James Francis Pantridge

Known as the “father of emergency medicine,” Professor James Francis “Frank” Pantridge, MD produced the first ever portable defibrillator with colleague Dr. John Geddes in 1965. The initial device was powered by car batteries and weighed 70 kg. By 1968, they had refined the design so that it weighed only 3 kg. Pantridge was also responsible for installing his instrument in ambulances, creating the pre-hospital coronary care unit known as the Pantridge Plan. The portable defibrillator would be essential to EMS and has been modified over the years to become the automated external defibrillator (AED). In 1967, The Lancet medical journal published an article hailing Pantridge and Geddes as “revolutionizing emergency medicine.”

Known as the “father of emergency medicine,” Professor James Francis “Frank” Pantridge, MD produced the first ever portable defibrillator with colleague Dr. John Geddes in 1965. The initial device was powered by car batteries and weighed 70 kg. By 1968, they had refined the design so that it weighed only 3 kg. Pantridge was also responsible for installing his instrument in ambulances, creating the pre-hospital coronary care unit known as the Pantridge Plan. The portable defibrillator would be essential to EMS and has been modified over the years to become the automated external defibrillator (AED). In 1967, The Lancet medical journal published an article hailing Pantridge and Geddes as “revolutionizing emergency medicine.”

Pantridge was born to small landowners in Hillsborough, County Down on October 3, 1916. He attended the Friends School and graduated in medicine from Queens University in 1939. He joined the army as a medical officer after WWII erupted. Pantridge’s heroism was immediately acknowledged and he was awarded the Military Cross for his work during the battle of Singapore. After the city fell to the Japanese, Pantridge was taken captive and held on the Siam-Burma railway and in the notorious death camp. It is believed that his interest in cardiology resulted from his survival of the usually fatal cardiac Beriberi – a disease in which the body does not have enough Thiamine – which he contracted there.

Pantridge returned to Belfast in 1945, but at the time he was only able to acquire a position as an adjunct lecturer in the Queens Department of Pathology. However, the University of Michigan offered him a scholarship and he worked with F. N. Wilson, the world authority on electrocardiology at the time. In 1950, Pantridge was appointed Physician at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast, where he remained until he retired in 1982, but not before chartering an internationally renowned cardiology unit. Pantridge died in 2004, at 88 years of age. – Michelle Meagher

Margaret Sanger

Credited with founding what is now Planned Parenthood, Margaret Sanger’s advocacy for birth control and women’s health overall stemmed from her own personal tragedy. Sanger was born on September 4, 1879 in Corning, New York to Anne Purcell and Irish immigrant Michael Hennessy Higgins. Margaret was one of her mother’s 18 pregnancies, only 11 of which survived. The pregnancies took a great toll on Anne’s body and her health deteriorated: she lost her life to tuberculosis at the age of 40. Margaret was only 19 years old and took her passing very hard.

Credited with founding what is now Planned Parenthood, Margaret Sanger’s advocacy for birth control and women’s health overall stemmed from her own personal tragedy. Sanger was born on September 4, 1879 in Corning, New York to Anne Purcell and Irish immigrant Michael Hennessy Higgins. Margaret was one of her mother’s 18 pregnancies, only 11 of which survived. The pregnancies took a great toll on Anne’s body and her health deteriorated: she lost her life to tuberculosis at the age of 40. Margaret was only 19 years old and took her passing very hard.

This event propelled Margaret into fighting for women’s right to use contraceptives, which were illegal under the Comstock Act. After becoming a nurse and seeing firsthand botched back-alley abortions and women with unwanted pregnancies, Margaret took her cause to the courts. She coined the term “birth control” in 1914, was indicted in 1915 for sending diaphragms via mail and then arrested in 1916 for opening the first birth control clinic in the country. Margaret continued on her crusade regardless, and in 1921 she founded the American Birth Control League, which would become the Planned Parenthood Federation. She also used her extensive knowledge to write health articles about birth control devices, providing information to interested parties. Margaret’s mission was not limited to the abolition of the Comstock Act (which she would witness in 1965) and greater information for women worldwide but also that more effective birth control would be made available. In 1951, Sanger sought the help of medical expert Gregory Pincus, who took on the project of inventing an oral contraceptive, and Katharine McCormack, who funded the research. In 1960, the first birth control pill, Enovid, was conceived. Margaret’s life-long dream and mission came into fruition and her battle was finally won. – Michelle Meagher

Anne Sullivan

Born in 1866, the eldest of five children of Limerick emigrants, Anne Sullivan did not have an easy childhood. Her parents, Thomas and Alice Sullivan, had departed for America at the peak of the Famine. They arrived illiterate and penniless, and settled in an Irish parish in western Massachusetts where Thomas earned a meager living as a farmhand. He was an alcoholic, reportedly abusive, and when Alice died when Anne was eight years old, he found the task of raising five children too trying and abandoned the family.

Anne Sullivan was a pioneer of blind and deaf education and is most famous for her work with Helen Keller. After their father left, Anne and her brother Jimmie were sent to an almshouse in Tewksbury, Massachusetts. Sullivan, who had been nearly blind since the age of five when she contracted a bacterial infection in her eyes, recognized that the best way out of the poorhouse was through a special education at the Perkins School for the Blind. She convinced Frank Sanborn, an inspector with the Mass-achusetts Board of Charities, to remove her from the house and sponsor her education.

Anne Sullivan was a pioneer of blind and deaf education and is most famous for her work with Helen Keller. After their father left, Anne and her brother Jimmie were sent to an almshouse in Tewksbury, Massachusetts. Sullivan, who had been nearly blind since the age of five when she contracted a bacterial infection in her eyes, recognized that the best way out of the poorhouse was through a special education at the Perkins School for the Blind. She convinced Frank Sanborn, an inspector with the Mass-achusetts Board of Charities, to remove her from the house and sponsor her education.

Despite beginning at Perkins illiterate and, by all accounts, uncouth, unruly, and hardened by life in the orphanage, Sullivan graduated from Perkins at the age of 20 as one of the most promising students, befriending numerous professors, and giving the valedictory address at the graduation ceremony. Formatively, while at Perkins, Anne befriended Laura Bridgeman, a resident of the institute who was deaf and blind. From her, Anne learned the hand sign alphabet she would later teach to Helen Keller, and learned techniques that aided Bridgeman (who was the first deaf-blind person to learn language) in acquiring sign language in general. When the Kellers wrote to Perkins asking for an instructor for Helen, the director of the school recommended Anne.

It is for this relationship that Sullivan is best known and their story has been well-documented. But less remarked on are Sullivan’s achievements in the field of deaf-blind education. Instead of maintaining a strict, grammarian method of instruction that had worked with Laura Bridgeman, she shifted the locus of education from language to aspects of Helen’s life. Anne ceaselessly “talked” to her, naming items Keller frequently used, to teach the association between word and object. Sullivan also expanded on a fledgling method of teaching deaf students to speak. By allowing Keller to touch Sullivan’s cheek when she spoke, Sullivan taught Keller to recognize the vibrations and eventually mimic them with her own mouth.

Sullivan died in 1936, after spending her entire adult life as a companion to Keller. “She occupies a commanding and conspicuous place,” Bishop James E. Freeman said at her funeral. “The touch of her hand did more than illuminate the pathway of a clouded mind; it literally emancipated a soul.” – Adam Farley

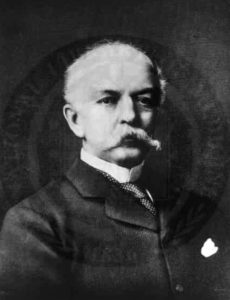

Dr. William Wilde

Dr. William Wilde, the father of Oscar Wilde, was a true Renaissance man of Victorian Dublin: an ear and eye surgeon, commissioner for the 1841 and 51 census, historian, Surgeon-Oculist to Queen Victoria, writer of medical journals and Irish folklore, and archaeological surveyor of the west of Ireland.

Dr. Wilde was born in 1815 at Kilkeevin in County Roscommon, the youngest of five children. His father was a doctor, inspiring William’s interest in medicine from an early age. Wilde earned his medical degree in 1837 at the age of 22 from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. Ophthalmology, the study of the eye and ear, was still very much in its infancy in the 1840s. Wilde immediately made a name for himself in the medical world by opening an ophthalmological surgery, which led to the founding of his own hospital, St Mark’s Ophthalmic Hospital for Diseases of the Eye and Ear, in Dublin. It was among the first in the British Isles to teach aural surgery, and would later prove an important center for research. In 1841, Dr. Wilde’s medical ability earned him a spot as medical commissioner for the 1841 census, a role he repeated in 1851. The 1851 census would later prove invaluable to Irish Famine research as it documented the severe population decline following the blight, and led to a knighthood for William Wilde in 1864.

Wilde’s literary output was equally brilliant. He became editor of the Dublin Journal of Medicine in 1845, and his Practical Observations on aural surgery and the nature and treatment of diseases in 1853 became the standard text on ear and eye surgery. A lover of the Irish countryside, he published numerous books on the archaeological landscape of Ireland. Wilde also retained a passion for Irish folklore, which he shared with his wife Jane. When visiting patients Wilde would sometimes accept stories and superstitions in lieu of payment. His writings are credited with establishing a cultural awakening of Irish folklore years before the Celtic Revival, a fact William Butler Yeats would comment on in his autobiography.

Dr. Wilde’s personal life clouded many of his achievements. Prior to marrying Lady Jane in 1851, Wilde had three children out of wedlock, whom he supported his entire life. Caricatures and gossip also surrounded the doctor. A local riddle of the time asked: “Why are Sir William Wilde’s nails so black?” Answer, “Because he has scratched himself.” The end of Wilde’s life was particularly tragic. A rape charge made by a former patient Mary Travers damaged his reputation, resulting in a libel court case in which Travers was awarded only one farthing in damages. Even in the midst of scandal, Wilde’s medical colleagues stuck behind him, openly supporting him in The Lancet magazine during the trial. Wilde died in 1876, at the age of 61, having left a strong imprint in the world of Victorian medicine and in the realms of Irish writing and folklore. – Matt Skwiat

Dr. Wilde’s personal life clouded many of his achievements. Prior to marrying Lady Jane in 1851, Wilde had three children out of wedlock, whom he supported his entire life. Caricatures and gossip also surrounded the doctor. A local riddle of the time asked: “Why are Sir William Wilde’s nails so black?” Answer, “Because he has scratched himself.” The end of Wilde’s life was particularly tragic. A rape charge made by a former patient Mary Travers damaged his reputation, resulting in a libel court case in which Travers was awarded only one farthing in damages. Even in the midst of scandal, Wilde’s medical colleagues stuck behind him, openly supporting him in The Lancet magazine during the trial. Wilde died in 1876, at the age of 61, having left a strong imprint in the world of Victorian medicine and in the realms of Irish writing and folklore. – Matt Skwiat

Professor Prem raj Pushpakaran ♡ പ്രൊഫസ്സർ പ്രേം രാജ് പുഷ്പാകരന് ♡ writes 2019 marks the centenary birth year of Joseph E. Murray, who did the first successful human kidney transplant on identical twins!!!