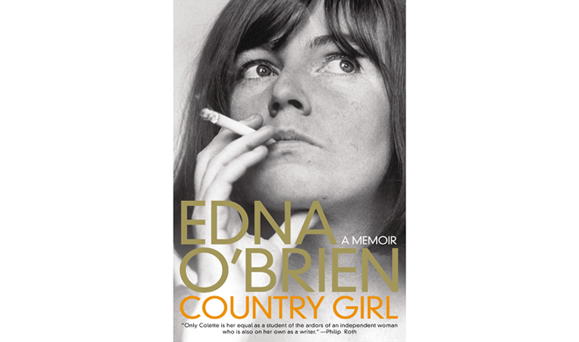

Edna O’Brien has published the memoir she swore she’d never write. Readers will be very glad she did.

“You can write and I will never forgive you,” said Ernest Gébler, Edna O’Brien’s then husband, after reading her manuscript for The Country Girls.

Published in 1960, O’Brien’s honest and intimate portrayal of two young women in the Ireland she had left behind was a breakthrough success in England and America. It launched her literary career (there would be two sequels and film adaptations) and established her as a singular, distinctly female voice at a time when the field of Irish writers was still overwhelmingly male.

Though he may have been the only one to put it so directly, Gébler was not the only one who would try to condemn O’Brien with his judgement. In Ireland, the author and her work, with its (by now tame) accounts of sex and intimacy, were denounced. The Country Girls was banned and burned. Archbishop Dennis McQuaid and then Taoiseach Charles Haughey concurred that it was “filth and should not be allowed in any decent home.” Years later, after her mother’s death, O’Brien would find the copy of The Country Girls she had sent to her “in a bolster case, with offending words daubed out in black ink.” One can only imagine the perverse care and attention to detail that must have taken.

In Country Girl, O’Brien’s sweeping new memoir, we meet her many iterations. Edna the child, growing up in the fallen Great House of Drewsboro in Co. Clare, with a father prone to outbursts of drunken rage and a mother who carried on determinedly but never quite got over the fact that the money she thought she married into was gone. There’s Edna the student, at a convent boarding school in Galway, where she develops her first consuming crush – on one of the young Sisters.

We see her enjoying her first taste of independence in Dublin, where, while training for four years to become a pharmacist, she discovers literature beyond the prayer books that filled her childhood home. She also discovers men. We witness her relationship with Gébler as it frees her from her family and uproots her from Ireland, and we understand her despair as it turns bitter, oppressive.

We meet Edna the mother. Edna the gracious hostess of the Swinging 60s, welcoming a wide-ranging list of stars into her Putney home. Robert Mitchum, Sean Connery, Paul McCartney, Marlon Brando, Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon, RD Laing, Ingrid Bergman, Judy Garland. One can’t help but recall the party scene in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Some are dear friends, many are passing acquaintances. Two men, who go unnamed, break her heart for a time. Both Norman Mailer and a young Jude Law steal quick kisses from her. Though impressive, the swirl of luminaries also highlights a palpable loneliness. O’Brien has often maintained that the writer’s life is, by nature, a solitary one.

The Edna we get to know the most is Edna the writer. In this regard, Country Girl is a portrait more intimate and complete than any we’ve seen before.

Her account of writing The Country Girls – more impassioned than most of her romantic reminiscences – drives home how vital the creative act is to O’Brien.

Isolated in suburban London and stuck in what has become a mostly loveless, imbalanced marriage, writing becomes her all. O’Brien finished The Country Girls in a mere three weeks, and here the urgency she felt is plain. After dropping her sons Carlo and Sasha off at school, she rushes back home to write and is instantly transported. “The wash of memory, and something stronger than memory, was so pervasive that I forgot I was in a semi-detatched house in London, with a small back garden that looked out onto another small back garden and an identical row of houses with red tiled roofs,” she recalls.

The writing is also a catharsis. She cries, but they are “good tears,” dredging up feelings she didn’t know she had. “The words poured out of me, and the pen above the paper was not moving fast enough, so that sometimes I feared they would be lost forever.”

One of the most important things about O’Brien, something she doesn’t belabor but something that must be recognized, is how much she gave up and risked in order to keep writing. Gébler, her sons (whom she almost lost in the ensuing custody battle), her mother, her reputation in Ireland. But barely for a second does O’Brien seem to reconsider or compromise.

Things get hard for O’Brien the writer. The fluidity she was blessed with while writing her earlier works eventually leaves her, and at one point, in a Singapore hotel on a book tour, she seriously contemplates taking her own life.

In a 2006 interview with this magazine, O’Brien said, “I would be much lonelier on this earth without literature, and I might even have gone mad. . . . Literature is the big bonanza, and writing is getting down on one’s knees each day and searching for the exact words.”

As much as it plagues her at times, writing is necessary for O’Brien – a kind of affirmation.

In the book’s prologue, she calls Country Girl “the memoir I swore I would never write.” But of course she had to write it. Because, resoundingly, she could.

Leave a Reply