ith the recent publication of the first volume of Beckett’s letters I started to recall the last time I met Beckett in Paris in 1988. We first met in April, 1985. It had been three years since our meeting at the café in the Hotel PLM. At noon. Noon being the time he had suggested. The suggested hour. At the time, there was the usual feeling one gets upon meeting one’s hero. Of sorts. Heroes coming in all sorts of sizes. Genres. Modes of discourse. Our first meeting was all that I hadn’t expected it to be: chatty, informal, with an air of melodious, yet melancholy, music to it. Yet, in its own way, it was sacrosanct. And so I looked forward to our next meeting, our last meeting. At the café of his choice, the PLM; at the time of his choice, noon.

I had primed myself by seeing En Attendant Godot several nights earlier in case one needed priming for such a meeting since my anxieties were much less pronounced than they were three years earlier. By now we had corresponded, almost called each other by first names, knew where each other lived. He had even consented to reading some blather I had written even though he couldn’t read much by then. Blather is all it was. Can’t remember what I had sent him.

I was early. Always early. One waits for Beckett, if one respects time. If one respects Beckett. It is also a kindness afforded to greatness. My time seemed expendable. I started to smooth my hair, tapped my fingers on the marble table, would have smoked had I allowed myself to do it. In between still another hair stroke, still another tapping finger, I saw him walk in and begin to look around. Gone were the grey greatcoat and the blue sweater now replaced with a knee-length, navy blue coat and an orange stocking cap. Tennies.

I walked across the room and tapped his shoulder.

“Mr. Beckett.”

“Mr. Axelrod,” he said as he turned.

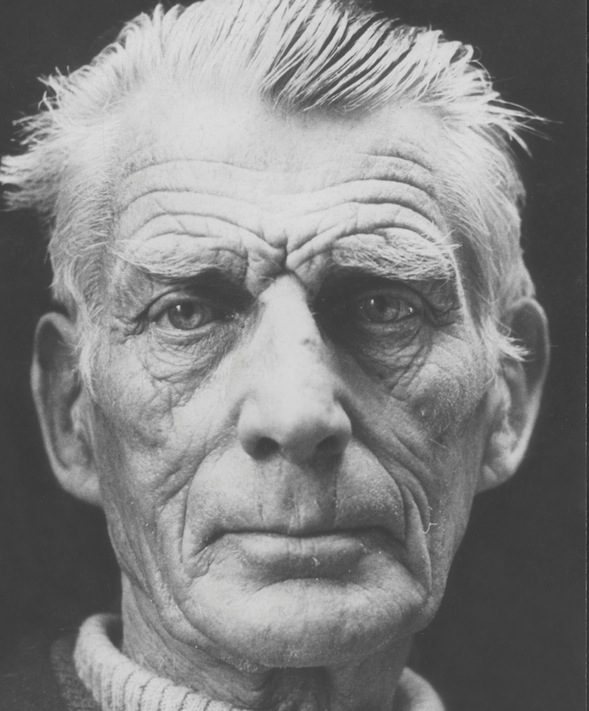

Beckett had chosen a booth, in a corner of the café, away from the window, beneath a coat rack. He removed a small, yellow cigar box and placed it on the table. Weathered hands, bent from the fabric of so many rigid pens. What I noticed this time that I hadn’t noticed three years earlier were the lines in his face. The creases, deep, curvilinear, like furrows that had swallowed certain secrets and kept them irretrievably harbored.

“The weather’s been so bad,” I said, “How do you manage? Morocco?”

A place he said he visited, at times, when Paris got too cold.

“My cottage,” he said, some miles outside Paris. In what direction he didn’t say. A reclusive habitat, no doubt. Doubt needed for reclusion. We ordered coffees: a café noir for him, a café crème for me. He seemed much thinner to me. Not a sickly thin, but an aged one, one that seemed to brook the onset of deliquescence. Deathlike, it seemed to me. I quickly discounted the idea.

“How’s the writing going?” I asked. A legitimate question of one writer to another regardless of the legitimate disparity in our talents.

Not well, he said, as he fiddled with his cigars.

“Writer’s block,” I said as a jest to me, to him, but he answered that it had never lasted so long. Then he looked at me with a smile that masqueraded nothing. A realization that the Muse was finally eluding him and he said, all things come to an end. And I realized that anything I said or did after that comment would never alter the fabric of that day, nor my life, nor his, nor any other life that had been or is or will be touched by his prose, by the supple salience of his prose which breathes across the page. I had often thought of myself as fairly facile in conversation. Able to pick up and move in any direction. But I suddenly found myself unable to think of anything to say that would liquidate the vacuum of the moment. Fortunately, the coffees came. A caffeinated respite.

I remembered reading, that morning, on the Metro, an article in the now defunct Paris magazine, Passion, titled “Les l00 Poids Lourds Des Lettres” with a picture of a certain Regine Deforges, a writer unknown to me, on the cover. The blurb beneath the title read ““Un hit-parade des l00 personnes-editeurs, écrivains, et…poètes-qui constituent le Tout-Paris des lettres.” The article certainly piqued my interest since I wondered in what category they had ensconced Beckett since such natives as Michel Butor and Maurice Blanchot and Claude Simon and Nathalie Sarraute were included as were exiles such as Milan Kundera. But though I looked and looked and looked again, Beckett was missing. Some poseurs were there, yes; some Beckett, was not. And so I said to him, ‘You’ve been living in Paris for all these many years and yet they haven’t included you among their ‘dinosaures des lettres Francaises.’ You live in France, you speak and write in French, yet they didn’t include you. Why do you think they did that?”

At first he looked puzzled by the exclusion, but then, with another smile, merely said, it’s okay, I forgive them. Maybe it was because he still thought of himself as Irish even after living fifty years in France or maybe it was because the redacteur en chef hadn’t edited the copy or perhaps the staff had thought him dead. At any rate, I didn’t forgive them.

“But when were you last in Ireland?” I asked.

Sixty-eight, he said, for a funeral. And then in a transition that wouldn’t have been a stain upon his craft, he said his mother was dead, and his brother was dead, and Blin was dead and so was Jack Yeats. And one could see the furrowed frown in his forehead as he held his hand to his head, thinking, perhaps repeating thoughts, or losing them, within the confines of time, time in the Vaucluse, Rousillon, with his wife, with others, time with Watt. The furrowed frown. Through some set of verbal perambulations he came to talk of his early work, how he couldn’t make it as a teacher since he felt he knew no more than his students. A last ditch writer, he called himself. No one took his work, no one looked at it. No one till Lindon, till Jerôme Lindon took his work. Without reservations. How fortunate he was, he said, to have found him, and how lucky he was to have found Roger Blin. And John Calder. How lucky I was, he repeated. How lucky he was. How lucky they were I thought, but he would have never said that. Never.

It’s somewhat difficult to reconstruct the scene, seen so many years ago now, two decades on, now after his centenary. I tend to think of how that meeting ended. Of what things I took away with me the last time I met Beckett. And I vividly remember two moments: first was his response to my simple-minded question: “What are you planning to write next?” acknowledged with the sublimely succinct answer, “All things come to an end.” With that statement there was nothing more to be said, nothing less. No symbols where none intended. It was over. One needed no redacteur to understand that, and yet hearing the words come from him rendered me depressed and sullen, rendered the day depressed and sullen. At the end of that chat, I suggested that, perhaps, he needed to go, to leave, to do whatever he needed to do since I didn’t want to take up any more of his time. He nodded, picked up his glasses, paid for the coffees and we both headed for the door.

The other moment was more sanguine. I recalled from our first meeting that he smoked Dutch cigars. Small ones. Small ones that came in a yellow cardboard box the brand of which escapes me. Holland stokjes or something of the sort. The ones he placed on the table when he arrived. As it was nearing his birthday, I had bought several boxes of those cigars to give to him as a present, as a gift and before he walked out of the café I told him I had something for him. I removed the crudely wrapped cigars from my leather bag, crudely wrapped as only I could crudely wrap them and handed the cigars to Beckett. He unwrapped the paper and when he saw they were the same cigars he smoked he looked at me with a look that was both perplexing and grateful, a look that would have suggested that what I had given him was a gift beyond all measure, a gift that was speechlessly invaluable. He asked me how I knew; I said I merely remembered.

And so they stayed a little while, Mr. Beckett and Mr. Axelrod looking at each other with Mr. Beckett’s hand on Mr. Axelrod’s shoulder, looking straight before him, at nothing in particular, and then Mr. Beckett thanked Mr. Axelrod, stuffed the boxes in his coat, bid Mr. Axelrod a safe trip home, shook his hand and left. A left turn, a right turn and he was gone though the sky, falling to the buildings, and the buildings falling to the river, made as pretty a picture, in the afternoon light, as a man could hope to meet with, on a waning day in April.

But the day wasn’t over for me. What I could not fathom was the line “All things come to an end.” Depressed and sullen discourse. One fathoms such a line from a dictionary of well-worn phrases perhaps, but not in the context of someone of Beckett’s literary station.

I recall I left the café, ambled, turning down aleatory alleys until I eventually found myself walking along the Seine, somewhere along the Seine, perhaps near the Hotel Lauzun, perhaps not, it didn’t really matter, repeating the line, the same line he spoke not that long ago, “All things come to an end.” The wind picked up. I couldn’t light my Dutch cigars. “No symbols where none intended.” How prescient he was. Fewer than two years later he was gone.

Mark Axelrod is a professor and former Chair of English and Comparative Literature at Chapman University, California. He is a multiple award winner for his work.

Leave a Reply