Tom Deignan looks at the rich and diverse influence of the Irish in the South

Statistics regarding the annual St. Patrick’s Day parade in Savannah, Georgia, are well known. When the 2006 festivities kicked off on March 17 at Abercorn Street, not far from Forsyth Park, it was the 182nd time the Irish in and around Savannah celebrated their heritage. “This parade has been named the second largest Saint Patrick’s Day Parade in the United States and rates as the largest annual single day celebration in the Southeastern United States,” parade chairman Jay Burke noted, adding that attendance to the parade has swelled to 400,000 in recent years.

But how did the Savannah Irish come to play such a prominent role in the Irish-American experience?

That question was posed about a decade ago by teachers and students at Georgia Southern University in Statesboro.

Located fifty miles northwest of Savannah, Georgia Southern opened its Center for Irish Studies in the mid-1990s, and also kicked off an ambitious oral history project which tracks not just the famous parade, but the broader experiences of Irish -Americans in this region.

The colorful celebration of St. Patrick’s Day in Savannah and the valuable scholarly research being done at Georgia Southern capture two distinct aspects of the Irish experience in Georgia, as well as the South in general.

The Savannah parade, as well as movies such as Gone with the Wind and authors such as Flannery O’Connor and John Kennedy Toole, remind people that there is an important Irish presence in the South. But too often such lessons are quickly forgotten.

For a certain kind of Irish-American — people like Chris Moser and James Webb — such historical amnesia presents a big problem. Perhaps the 21st century will finally be the time when the story of the Irish in the Southern U.S. is told.

America’s Other Irish

Chris Moser is the brainchild behind America’s Other Irish, a documentary he is producing along with Redwine Productions of Atlanta and Borderline Productions of Belfast.

The W.B. Yeats Foundation of Emory University in Atlanta is sponsoring the project. Georgia Southern’s Center for Irish Studies is also contributing research. The Ulster-Scots Agency in Northern Ireland, the Northern Ireland Film and Television Commission, and humanities councils in Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina have thus far provided funding for America’s Other Irish.

This is important because it suggests region-wide (not to mention trans-Atlantic) support for a project which explicitly seeks to overturn the notion that the story of the Irish in America is one which predominantly unfolded in Northern cities such as New York, Boston, Chicago and Philadelphia.

Kirby Miller is among the academic all stars who have signed on as consultants for America’s Other Irish, which is expected to be shopped to TV stations sometime next year.

Indeed, there is growing evidence that Americans are finally beginning to grasp the uniqueness and importance of the Southern Irish contribution to U.S. history.

Consider the creation of institutes for Irish studies at places such as Georgia Southern, not to mention the Universities of Kentucky, Memphis and South Carolina.

Meanwhile, cities such as Atlanta these days are home not merely to St. Patrick’s Day Parades and AOH and Hibernian Benevolent Society groups. Atlanta is also home to an annual Celtic festival, a quarterly Celtic publication, and a Gaelic Football club, which recently celebrated its 10th anniversary.

Last year, author James Webb wrote a best-seller in which the Southern Irish were key players.

What links these seemingly disparate pursuits is a willingness to include the largely Protestant, so-called Scots-Irish, in the broader narrative of the Irish experience in America.

Born Fighting Irish

Nothing captures this quite so strongly as Webb’s passionate, at times personal, best-seller Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America.

“[The Scots-Irish] people gave our country great things, including its most definitive culture. Its bloodlines have flowed in the veins of at least a dozen presidents, and in many of our greatest soldiers. It created and still perpetuates the most distinctly American form of music. It is imbued with a unique and unforgiving code of personal honor, less ritualized but every bit as powerful as the samurai code. Its legacy is broad; in many ways defining the attitudes and values of the military, or working class America, and even the peculiarly populist form of American democracy itself. And yet its story has been lost under the weight of more recent immigrations, revisionist historians, and common ignorance,” Webb laments.

He continues: “The contributions of this culture are too great to be forgotten as America rushes forward into yet another redefinition of itself. And in a society obsessed with multicultural jealousies, those who cannot articulate their ethnic origins are doomed to a form of social and political isolation. My culture needs to rediscover itself, and in so doing to regain its power to shape the direction of America.”

With this new appreciation of the Scots -Irish, and a broader understanding of the Southern Irish in the U.S., the day may yet come when John Fitzgerald Kennedy is remembered as the second great Irish president.

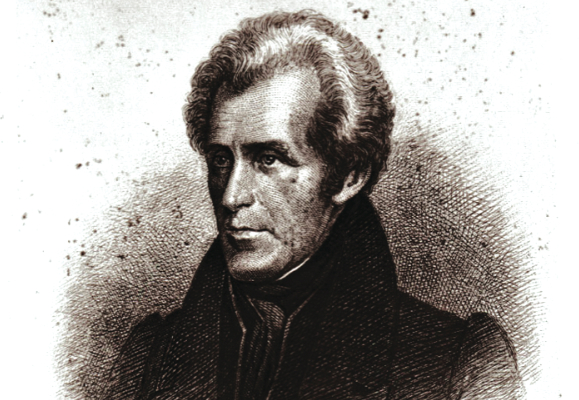

After all, over a century prior to Kennedy’s election, Andrew Jackson — native of South Carolina, son of immigrants from Carrickfergus, Antrim — ascended to the White House.

Different Religions

Of course, though people are starting to grasp the importance of the Southern Irish, there are some facts to acknowledge. In the years after the Irish Famine of the 1840s, the Irish population of some Northern cities swelled to almost 40 percent.

By contrast, according to The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America: “Only about 4.2 percent of the white people in the South in 1850 were foreign-born, and most of them were concentrated in such urban places as New Orleans, Mobile and Charleston.”

In short, Irish immigrants were few and far between in this region. But that does not mean the Irish influence was unsubstantial. What has to be acknowledged is that while Irish Catholic immigrant influence may have been small, the second and third-generation Scots-Irish (largely Presbyterian) influence was large.

Georgia again serves as a useful example. As scholar Edward Shoemaker has written, the Irish who did settle in Georgia “played a series of important social and economic roles, which evolved as Georgia developed from a frontier outpost into a settled society.”

He continues: “During the 18th century the Irish helped to populate the frontier settlement of this southernmost British colony. In the nineteenth century, they filled vital niches in a labor-short economy.”

Those toiling away at Georgia Southern’s Irish studies program concur.

“Irish influence is everywhere present in Georgia, from place names like Dublin and Burke and Blakely Counties to literature,” GSU’s web site notes, adding that the second Royal Governor (1757-1760) of the colony was the Monaghan-born naval explorer Henry Ellis.

In fact, the Irish were present at the creation of Georgia as a British colony in 1733.

That year, “a shipload of forty Irish convicts received grudging permission to land at Savannah on condition that the passengers commit themselves to the defense of the settlement,” Edward Shoemaker writes.

In the 1760s, Armagh native George Galphin co-sponsored a heavily Irish settlement called Queensborough, near what became an earlier capital of Georgia. Galphin and his Irish and Scottish partners advertised the venture in Irish newspapers.

Canals, Railroads and Immigrants

In the decades that followed, the waves of Irish immigration to Georgia were not unlike those seen in regions all across the U.S. The first waves set out to tame the wilderness and often do battle with Native Americans.

By the 1820s and 1830s, labor was needed to construct valuable canals, and Irish immigrants were more than up to the task. This brought the first significant numbers of Irish Catholics to Georgia, whose first colonial charter actually banned Catholicism.

The next major source of labor for Irish immigrants were railroads, built throughout the 1840s and 1850s, including the Central of Georgia, linking Savannah and Macon.

The Western and Atlantic later connected Atlanta and Chattanooga, Tennessee.

With the Irish population growing, services for them spread. Irish merchant shippers William Graves handled money transactions between Ireland and the U.S. for immigrants (a majority from Wexford) in Savannah. By 1850, Georgia became a Catholic diocese, led by Dublin bishop Francis X. Gartland.

By the time the U.S. Civil War broke out in 1861, there were enough Irishmen in the South to raise Irish brigades in eight of the 11 states that made up the Confederacy.

There were an estimated 85,000 Irish immigrants living in the Confederacy, according to the 1860 census.

Scholars Grady McWhiney and Forrest McDonald have said that “the overwhelming majority of the people who settled the South were ‘Celts,’ by which they mean ‘people from the British Isles who were historically and culturally non-English.’”

What’s Next?

But what does this all mean? Is there any way that common threads can be found running though the narrative of the Irish Catholic Northern experience and the Scots- Irish Southern experience? Perhaps we can return to the White House for an answer.

There were two times that a near-majority of the electorate feared that the trailblazing Democratic nominee for president was too much of an outsider, would empower the “wrong types” of people and would, in all likelihood, endanger American culture.

In 1828 this was said about Andrew Jackson, whose base was decidedly unaristocratic Scots-Irish frontiersmen. This was also said in 1960 about JFK, supported by Irish Catholics, civil rights leaders and blue collar union members.

Forging such historical links should be a main focus of Irish-Americans in the 21st century. ♦

I must say that whole McDonald and McWhiney analysis is bullcrap most southerners are a mix of celtic and anglo-saxon ancestries. The entire southern aristocracy was of english origin. Along with the fact that they are the largest ancestorial group in the US by population having settled the colonies first, but the sad thing is most southerners as most put American which is different as they had put English before the 2000 census. If anything having two people with Scottish surnames is obvious bias and lying you have to read the DNA and census data.

My Hogan ancestors settled in Virginia after Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland. One ancestor, Dermot Hogan (Durmuid O’hOgain), was listed in John O’Hart’s Landed Gentry When Cromwell Came to Ireland, published in 1881. He and his brother, my direct ancestor, died the same year that British parliament passes legislation to procure properties confiscated during the eleven years war. His son, Patrick, was 17 years old. He and his son, William Hogan, settled in Virginia during colonial times. Later generations married the British colonists that settled the area, including the Mills, Pate and Carner families. They fought in the American Revolution and American Civil War. They were already here when the Scots-Irish settlers arrived and would have found much in common with them. The Irish have been in the South much longer than this article, or any other I have read, would dare to suggest.

Scott, I am a direct descendant of Hugh Hogan of New Kent and Hanover Counties in 1700 Virginia .Hugh had several known sons, John, William, and Zachariah Hogan of Louisa Counties. Do you have any information of Hugh Hogan ? Thank you, Don Hogan

There were also a large group of Irish who came as indentured servants and were treated similarly to slaves. I did not learn about this until last year and was absolutely shocked. Some of the abused became abusers after their indenture ended (plantation overseers) and many distanced themselves from the Southern experience at the outbreak of Civil War, heading west, especially to California..

Scot Irish link to North American country music is acknowledged. But the only unique American music is jazz.

I would love to talk to you about my late father’s autobiography The Way it Was by Malachy Donoghue. It has been on amazon and kindle’s hot new releases list, best seller list and best travel books list. It is a riveting read about Mal’s life growing up in Roscommon, Ireland in the 1920s and at the age of 11 after a family emergency taking over the family farm and keeping his family members alive. He later moved to Fairbanks, Alaska, on a whim and working in the goldfields for 7 harrowing years. He eventually landed in NY and lived there for 50 plus years before passing away at the age of 89. I self published the book after he passed and it is getting tons of international media coverage and rave reviews. I would love to do an interview with you or just maybe do something on your blog about the book as I think you and your followers will not be able to put the book down. Everyone I speak to says it’s the next Angela’s Ashes. Go to facebook page The Way it Was @malachydonoghue to learn more and go to amazon and get yourself a copy today. Hope to hear from you soon!

Not only Andrew Jackson, but several other Presidents, from Chester Arthur to Bill Clinton, were of Scots-Irish origin. Additional Presidents, including Barack Obama, had some Irish or Scots-Irish ancestry. Donald Trump is the first President since Eisenhower without some roots in the Emerald Isle.